Contents

Contents

Chapters

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 - France and the New World

- Chapter 2 - The Treaty of Paris and its Consequences

- Chapter 3 - The Diplomacy of Vergennes

- Chapter 4 - Silas Deane's Mission

- Chapter 5 - Beaumarchais

- Chapter 6 - Events of 1776

- Chapter 7 - Franklin

- Chapter 8 - The Privateers

- Chapter 9 - La Fayette

- Chapter 10 - The Ambition of the Comte de Broglie

- Chapter 11 - America and the French People

- Chapter 12 - Progress of the Negotiations

- Chapter 13 - France Sends a Plenipotentiary

- Chapter 14 - The French Fleet

- Chapter 15 - La Fayette to the Rescue

- Chapter 16 - The Arrival of Rochambeau

- Chapter 17 - The Sinews of War

- Chapter 18 - The French Troops in Americ

- Chapter 19 - The Expedition of de Grasse

- Chapter 20 - The Yorktown Expedition

- Chapter 21 - Yorktown and de Grasse

- Chapter 22 - Closing Years of the War

- Chapter 23 - French Impressions of America

- Chapter 24 - American Envoys in France

- Chapter 25 - Negotiations for Peace

- Chapter 26 - Conclusion

On Friday the 6th of February, 1778, plenipotentiaries met in Paris to sign a treaty for which there had been no precedent in history, and of which there has been no imitation since. Three of them represented a government that was independent only in its own estimation; they were called Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee, and were delegates of the new-born “United States of North America”; the fourth represented the oldest monarchy in Europe, and was Conrad Gerard de Rayneval, destined to be later the first diplomat ever accredited to America.

Article II of the treaty provided that “the essential and direct end of the present defensive alliance is to maintain effectually the liberty, sovereignty and independence absolute and unlimited of the said United States.” By other articles France pledged herself not to lay down her arms until this independence had been achieved, and, whatever be the delay, cost, or losses, to neither claim nor accept anything for the help thus provided. She even specifically consented that the harshest of the conditions of the 1763 treaty of peace with England be maintained: if conquests were made ” in the northern part of America,” the conquered land would be annexed to the United States, and not to the country which had settled Canada and possessed it until that peace.

A treaty of commerce had been signed on the same day, and in the same spirit, France reserving for herself no advantage but subscribing an agreement to which any nation, England included, would be welcome to be a party when it chose. France, wrote Franklin, has “taken no advantage of our present difficulties to exact terms which we would not willingly grant when established in prosperity and power.” France, grumbled Mr. de Floridablanca, prime minister of Spain, when the treaties were read to him, “is acting like Don Quixote.”

The treaties signed on the 6th of February, 1778, were certainly unprecedented. So much so that, in some minds, and for a long time (in that of John Adams, for example, to the last), doubts remained. Was that really possible? Were there no secret articles? No, there were none. Would France keep her word, and, if success was attained, reserve for herself nothing on a continent two thirds of which had been hers? She would, and did, keep her word. Even Washington had had his doubts and had wondered when, time and again, plans were submitted to him for an action in Canada, whether there was not in them “more than the disinterested zeal of allies” (Nov. 11, 1778). The event proved that such fears were groundless.

Extraordinary events have extraordinary causes. This was a unique one; how did it come about?

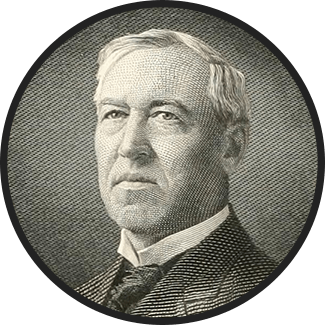

The answer will be found in the volume to which the finishing touches were being put by Mr. James Breck Perkins when death removed him from the place he so worthily filled among lovers of historical studies, and from Congress, where his sense, experience, and wisdom as chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs will long be remembered. There are in his book no better chapters than those in which he makes clear what took place and why.

Two principal motives explain what happened: a chief one which has usually been more or less neglected, and a secondary one to which historians usually give the foremost place.

The latter is the obvious one of France’s animosity against her old enemy, Great Britain, the winner at the Plains of Abraham, the deviser of the harsh conditions of 1763. But because it is obvious and needs neither research nor even thought to be put forth, that has often been alleged as the chief, if not the unique, motive for what took place. Two distinct influences, in fact, acted together to bring about the alliance of France with the New Republic: that of statesmen and that of the nation. Among certain statesmen, as among many officers, the desire for reprisals was a potent factor, and the rebellion of the colonies was welcomed, chiefly because they rebelled against England. Among the French people at large it was quite otherwise: the rebellious colonies were popular, not especially because they wanted to throw off an English yoke, but because they wanted to throw off a yoke.

It must not be forgotten that the period of the War of Independence was not coincident with one of Anglophobia in France, but on the contrary with one of Anglomania. Everything English was admired, and, when possible, imitated: manners, literature, philosophy, sport, parliamentary institutions, and above all, writes one of the earliest French supporters of the colonists, Segur, “the liberty, at once calm and lofty, enjoyed by the entire body of the citizens of Great Britain”; Frenchmen “were crazy about the English institutions.” It was the period when people would go to London in order to “learn how to become thinkers,” and to learn also how the stiff rules of old should be discarded, whether the matter was of the laying out of a garden, of the government of empires, or the writing of a tragedy. The year of the Proclamation of Independence was also the one during which the complete works of Shakespeare, translated by Le Tourneur, took Paris by storm, and were published by subscription, the King and Queen heading the list. “All the youth of Paris is for Le Tourneur,” wrote indignant Voltaire.

The anti-English sentiment existed indeed only within somewhat narrow limits. Even among military men that sentiment was not a universal one: examining the causes why so many young officers, and he himself among them, longed to play a part in the great struggle, Segur enumerates the usual motives, such as a “desire of glory and of rank,” the service due to the King and country, and concludes that, above all, they were impelled “by a yet more exalted principle, a sincere enthusiasm for the cause of American liberty.” Of a desire to humble the old enemy not a word: people were rushing “to the field of battle,” says he further, “in the name of philanthropy.”

Liberty, philanthropy, natural rights, those were the magic words that were then stirring not only writers and thinkers, but the very masses in France. The day of unbending dogmatism and heavy yokes had passed; privileges subsisted, but had scarcely any defenders left; the aspirations were immense for a greater equality, more breathing space, simpler lives, more accessible knowledge, free discussion of common interests. Montesquieu, Rousseau, Voltaire, the encyclopedists, had said their say; it had sunk deep into the nation’s mind. Those who could read had read the books, the others had been talked to about them. The power of public opinion and of illiterate masses had wonderfully increased, more even perhaps than is shown in the present work. Peace had not yet been signed at Versailles when Necker published his epoch-making “Compte Rendu,” enabling the whole nation to be judge of its own interests; peace had just been signed when he printed his “Administration des Finances de la France,” of which, in spite of the opposition of his successors in office, eighty thousand copies were sold. The days indeed were not far off when the nation would show that it had ideas of its own, and would draw the famous Cahiers of 1789, some being compiled by mere peasants who offered excuses for their rough mountaineers’ orthography.

Add to this that, while old ideas, old rules, the old Regime in its entirety, were losing ground, youthful enthusiasm and ardor pervaded the nation. Two years before American Independence was proclaimed, the correspondence of Grimm and Diderot tells us of the effect on the French public of “those general and exaggerated maxims that fire the enthusiasm of youths and would make them run to the world’s end, and abandon father, mother, brother, to come to the assistance of an Esquimau or a Hottentot.”

Now the time had come to run to the world’s end and, like La Fayette, leave wife, child, and the pleasures of an easy life, for something greater indeed than the fate of any Hottentot. What was at stake was in fact what the French of the new generation held dearest. All the reports that came concerning Americans showed them lovers of liberty, practisers of equality, accepting no privileges, tolerant of all creeds, leading honorable and simple lives, in their poetic solitudes.

Deane, Lee, and Franklin appear in Paris, and seem “sages, contemporaries with Plato, or republicans of the age of Cato and of Fabius” (Segur). In the eyes of Voltaire the insurgents are animated by the truest philosophical principles, they fight for “reason and liberty.” The constitutions of the principal states are translated into French a little later under the supervision of Franklin, and the admiration is unanimous for those “charters of liberty.” French officers leave Versailles, the soldiers leave their villages and their garrison towns: what they find on reaching America fulfills, in most cases, their anticipation. They prove friendly judges; what they observed is thus described by one of them: “Indigence and brutality were nowhere to be seen; fertility, comfort and kindness were everywhere to be found ; and every individual displayed the modest and tranquil pride of an independent man who feels that he has nothing above him but the laws.”

No wonder, when all this is considered, that French public opinion was wrought up to the highest pitch and that it played, as it did, a decisive part in the grand drama. The animosity against England still harbored by some statesmen and soldiers in this period of Anglomania, would never have achieved the momentous results that were at stake. The King hesitated, his ministers (Vergennes excepted) fell into periodical doubts; Necker, who held the purse- strings, was a confirmed Anglophile; official reports on America were not all as rose-colored as the private letters of a La Fayette, a Segur, or a Chastellux. But public opinion never wavered. “During the five years that the war continued,” says Mr. Perkins, “the French people remained constant in the cause.” “On all sides,” wrote that same good judge, Segur, “public opinion urged a regal government to declare itself in favor of republican liberty, and even murmured at the irresolution and delay. The ministers gradually yielding to the torrent were, at the same time, alarmed at the prospect of a ruinous war.”

Ruinous it was indeed, costing the French treasury seven hundred and seventy-two millions of dollars; but public opinion remained faithful to the struggling states. The people groaned under the weight of taxation, but never grumbled at the expense for such a cause. Peace came, France kept her word; she did not try to recover any of her possessions on the American continent; she made a pro-American peace, not an anti-English one. Public opinion again was fully satisfied: what it wanted had been secured; there were no protests against the moderation shown towards the adversary; the joy was universal. Years after the war the same pro-American feelings which had apparently taken deep root still prevailed, as shown by the French National Assembly’s adjourning at the news of the death of Franklin; the French army going into mourning at the death of Washington, and the glowing eulogies of the new republic still sent home by its French visitors. Talleyrand came to America in 1794, so as to become acquainted, be Says, with “that great country whose history now begins.” His impressions are most favorable to a people “that shall one day be a great people, the wisest and happiest on earth.” He observes, it is true, in 1797, that the bulk of the trade goes to England, so that “Independence, far from having been hurtful, has proved, in many respects, helpful to that country.” But he observes this with perfect equanimity. “Americans,” writes General Moreau, in 1806, from Philadelphia, “are good people…Their progress in trade and navigation is truly wonderfu…One enjoys in their country the most boundless liberty, and there is no abuse…Men who have lived under such a government will never allow themselves to be shackled again.”

On all this, the author of the present work has much to say that should be remembered, and never, perhaps, has the question of how and why what happened could take place, been so clearly put before the American reader. The existence of an anti-English feeling in certain French milieus is not denied and it receives no less than its due in the first chapters. But the other side of the question is then placed in such full light that few readers will fail to agree with Mr. Perkins’s conclusion that “public opinion became, at the last, the most potent factor in controlling the decision of the French government…It was the popular enthusiasm for American liberty which penetrated the council chamber and influenced the ministers in their decision, even if they failed to recognize such a motive.”

Those views are the worthier of notice since Mr. Perkins never allows himself to be led astray by enthusiasm or sentimentality. No excessive indulgence marks his judgments on men or deeds, be they French or American. This probity in his views is on a par with the austerity of his style, an austerity which, far from deadening, enhances, on the contrary, the dramatic interest, and the romantic charm, not to say the poetry of the events.

Once more, under this trusty guide, the reader follows, scene by scene, the progress of the momentous drama, with its alternatives of success and defeat, fights by land and by sea, lucky or fruitless negotiations, fleets crossing and recrossing the ocean, cities taken and lost, great New York impregnable with its fortifications and its eleven thousand English and Hessian regulars, the key, as it seemed, of a situation that was in reality to be decided under the bastions of a small borough along the Chesapeake. Before us appear soldiers and sailors of fame: Wayne, Greene, Rochambeau, d’Estaing, de Grasse, Paul Jones, La Fayette, the grand image of Washington towering above all the rest; but room is found for many others great and small, evoked before the reader in the clear light of the author’s lucid style: circumspect and steady Vergennes, who favored the insurgents from the first, and remained to the last “consistent and upright,” Gerard and La Luzerne, my cool-headed predecessors, impetuous Beaumarchais, who has his statue in Paris for that product of his brain, “Figaro,” and deserves a memorial in America too for that other product of his brain, “Hortalez and Co.” The hard pilgrimage is told us of American negotiators sent by an optimistic congress “to various European courts, but few of them were received,” and they secured, at best, promise of friendship for the time when the danger should be over. “The affairs of the colonies,” wrote Frederick II to one of his ministers, “are yet in too great a crisis; so long as their independence is not more firmly established, all immediate commerce under my flag seems to me too perilous and fraught with too great inconveniences for me to run such risks.” He thought, however, that the French would do well to run any risks, and, at the time when they had not yet taken sides, expressed himself as shocked at their “pusillanimity.”

France and the States went their way, which led them to Yorktown and to one of the most honorable treaties of peace ever concluded – so honorable because it was so just and moderate.

In a sort of postscript Mr. Perkins carries the story down almost to our own days, recalling the difference of feeling toward America which, for well-known causes, existed in France, between the Imperial Government and the nation, at the time of the War of Secession. Once more on the eve of a transformation accompanied by terrible woes, the nation manifested how eagerly her wishes went to the maintenance of the then only great republic; a popular subscription was opened (of two cents per bead, so that the poorest might take part) for a medal to be struck in commemoration of the life and death of Lincoln, “honest man,” as the inscription reads, “who abolished slavery, reestablished the Union, saved the Republic, without veiling the statue of Liberty.”

In the midst of the conflicting judgments passed on the part played by France in the War of Independence, from that of Mr. de Floridablanca, who considered us quixotic, to those of Jay or Adams, who could never believe that we had no concealed plans, posterity will probably ratify the conclusions of Mr. Perkins’s whole study, well condensed by him in the following admirable words: “The arguments on which statesmen based their action were not justified in the future. But the instincts of the French nation were right: they assisted a people to gain their freedom, they took part in one of the great crises of modern progress, they helped the world on its onward march… The reward is not to be found in more vessels sailing laden with wares . . . but in the consciousness of the unselfish performance of good work, of assistance rendered to the cause of freedom, and to the improvement of man’s lot on earth.”

J. J. JUSSERAND.

WASHINGTON March, 1911.