Contents

Contents

During the Revolutionary War, both sides used political cartoons to portray their perspective of events from the battle, mock the enemy, and promote the righteousness of their cause. Some cartoonists also expressed opposition to the war, and criticisms of military commanders.

These political cartoons were often published in newspapers or printed pamphlets as war propaganda, and were sometimes seen by hundreds of thousands of people.

Below, we’ve provided some examples of political cartoons produced during the American Revolution, and explained their context, and the political messaging being conveyed.

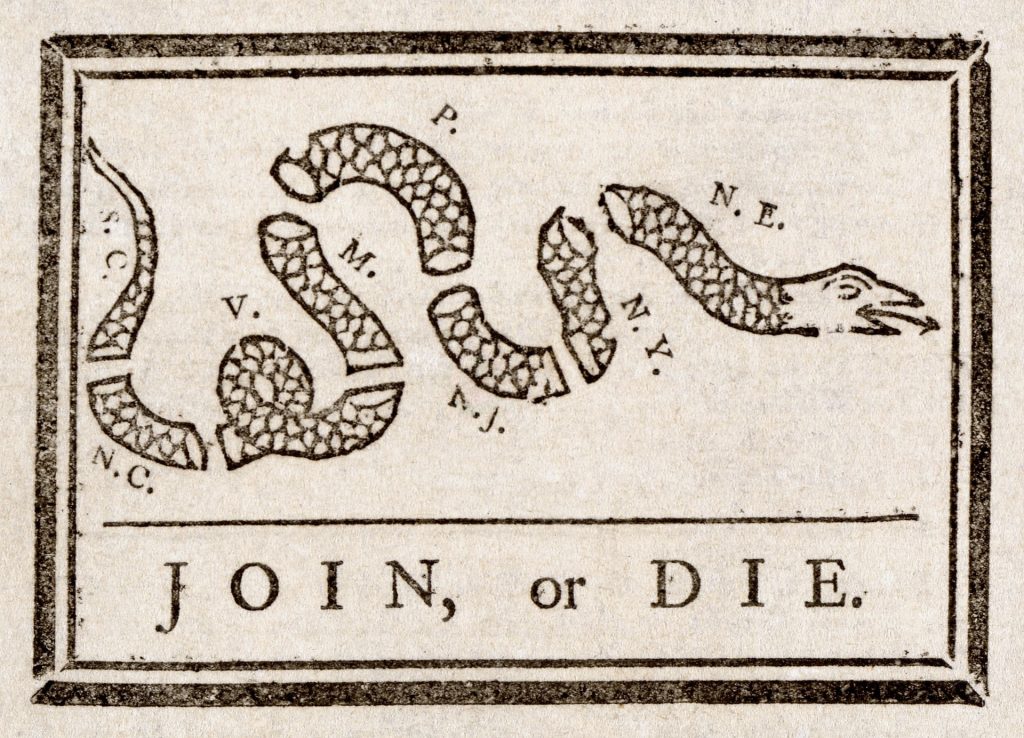

1. Join or Die by Benjamin Franklin, 1754 (American)

This cartoon was published in 1754, long before the American Revolution, but Benjamin Franklin’s imagery continued to be used throughout the Revolutionary War.

Believed to be the first political cartoon in American history, in this work, Franklin was imploring the colonies to stick together, to protect against the French and their Native American allies during the French and Indian War. The rattlesnake is depicted cut into pieces, symbolizing the disunity of the colonies at the time.

The rattlesnake imagery became much more popular during the Revolutionary War, when it was used to symbolize colonial unity and resistance. Its most famous usage was arguably on the Gadsden Flag, used by the Continental Navy, but the snake also found its way into political cartoons on both sides of the conflict.

2. The bloody massacre perpetrated in King Street Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regt. by Paul Revere, 1770 (American)

On March 5 1770, British troops opened fire on an angry mob outside the Boston Customs House, killing five people and wounding six more.

The Patriot and Loyalist sides immediately tried to put their own spin on the event. Patriots called it the “Boston Massacre”, and Paul Revere produced an engraving of the incident, which was printed and distributed in the weeks and months after the killing.

Revere’s depiction of the event is considered to be highly sensationalized, when compared to eyewitness accounts.

He portrays the British in a line, with their Captain, Thomas Preston ordering them to open fire on cowering civilians. In reality, the volley of shots was more of a panicked response to the harassment of the crowd, and Preston did not give the order to open fire.

3. The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man, or Tarring and Feathering, by Philip Dawe, 1774 (English)

On January 25, 1774, John Malcom, a British customs officer and staunch Loyalist, was kidnapped by an angry mob in Boston, after he struck a boy with his cane, knocking him unconscious.

Malcom was kidnapped from his house and tarred and feathered. He was then taken to the Liberty Tree, beaten up, and threatened with hanging.

Philip Dawe later published this cartoon depicting the event, portraying the colonists as lawless savages, and showing them forcing him to drink tea, which did occur by some accounts. The Boston Tea Party is shown in the background.

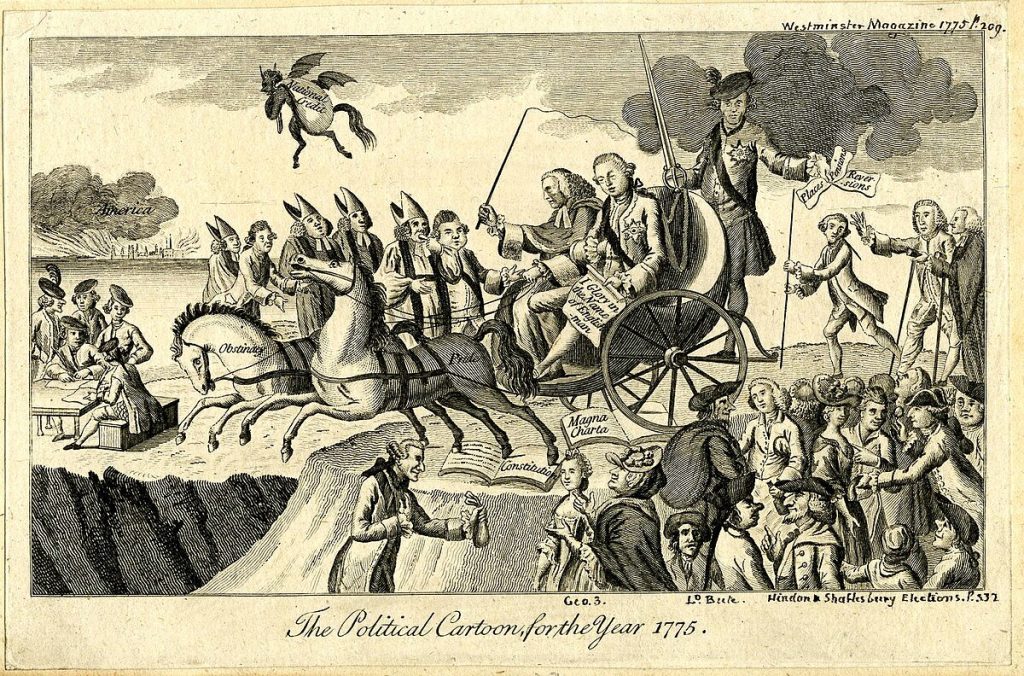

4. The political cartoon for the year 1775, unknown artist, 1775 (English)

This is an example of a British cartoon displaying opposition to the Revolutionary War, released in 1775. The artist and its origin are unknown.

It depicts the British monarch, King George III, and Lord Chief Justice, Lord William Mansfield riding a horse-drawn carriage towards an open chasm. The horses are labelled “Pride” and “Obstinacy” (meaning, stubbornness) and they are trampling over the British constitution and the Magna Carta, inferring that warmongers in parliament are disregarding British law.

Although Lord Mansfield was not Prime Minister, he had significant power as Lord Chief Justice, and he was known for his belief in the absolute sovereignty of the British Parliament, including their right to tax the colonies without their consent. In 1829, John Quincy Adams described him as “more responsible for the Revolution than any other man”.

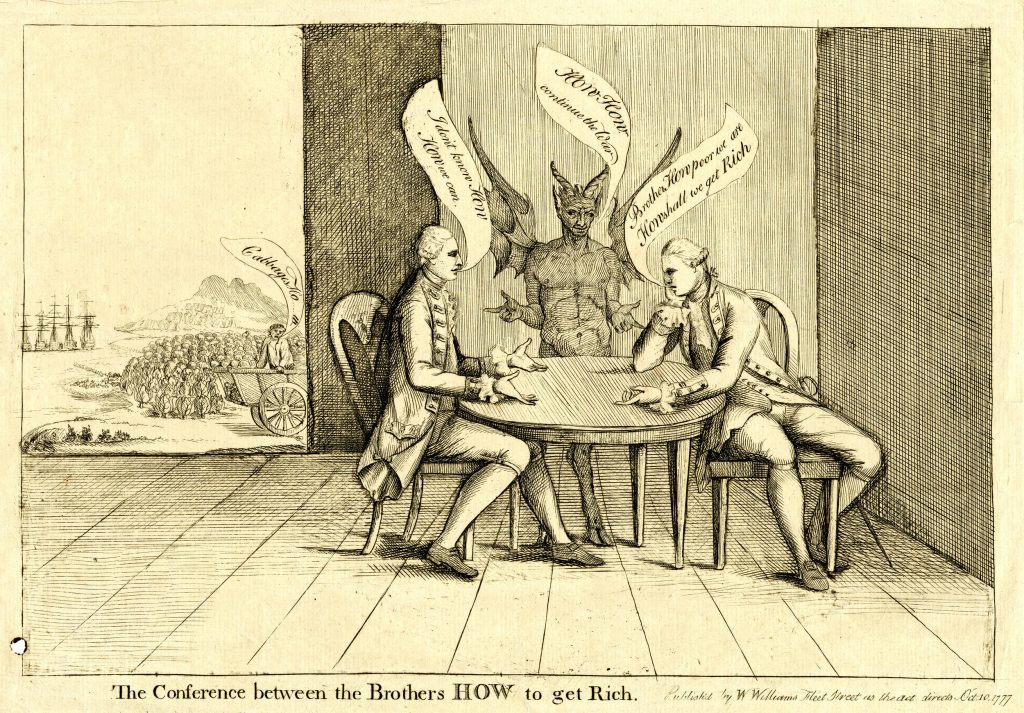

5. The Conference between the Brothers HOW to get Rich, by W. Williams, 1777 (England)

This is another anti-war cartoon, published in Great Britain.

It depicts Richard Howe, British Army leader, and his brother William, commander of the British Navy, sitting at a table, with the Devil between them.

William, pictured on the right in naval attire, ponders “…how shall we get rich” and the Devil responds “How, How, continue the war”. “How” is used as a play on words with the brothers’ surname.

At the time, Richard and William Howe were two of the most important British military leaders during the American Revolution. However, their military strategies were questioned by some in Britain, and the cartoon’s author implies that they are only fighting for their own self-interest.

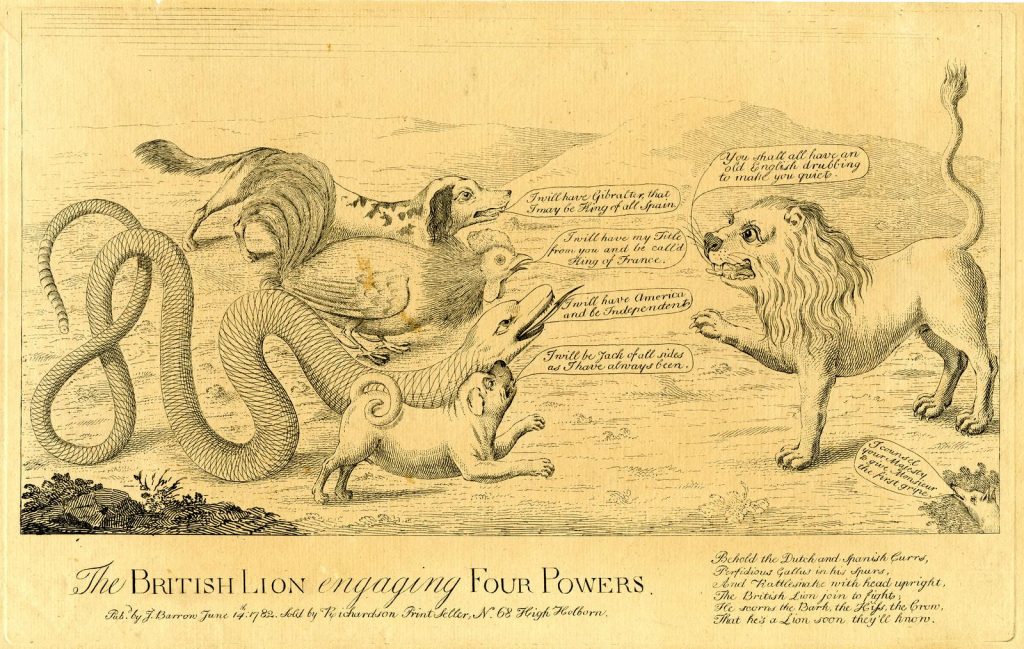

6. The British Lion engaging four powers by J. Barrow, 1782 (English)

In this cartoon, the artist criticises Britain’s enemies in the late 18th century. As well as the American Patriots, Spain and Holland are also included, portrayed as dogs. France is also included, depicted as a rooster, its national bird, while England is depicted as a lion.

The animals on the left are shown as wanting something from England. For example, Spain states that it will have Gibraltar, and the American serpent says it will achieve independence. Holland is criticised for playing both sides of the war – its animal, the white pug, states “I will be Jack of all sides as I have always been”.

In response, the lion retorts “You shall have an old English drubbing to make you all quiet”.

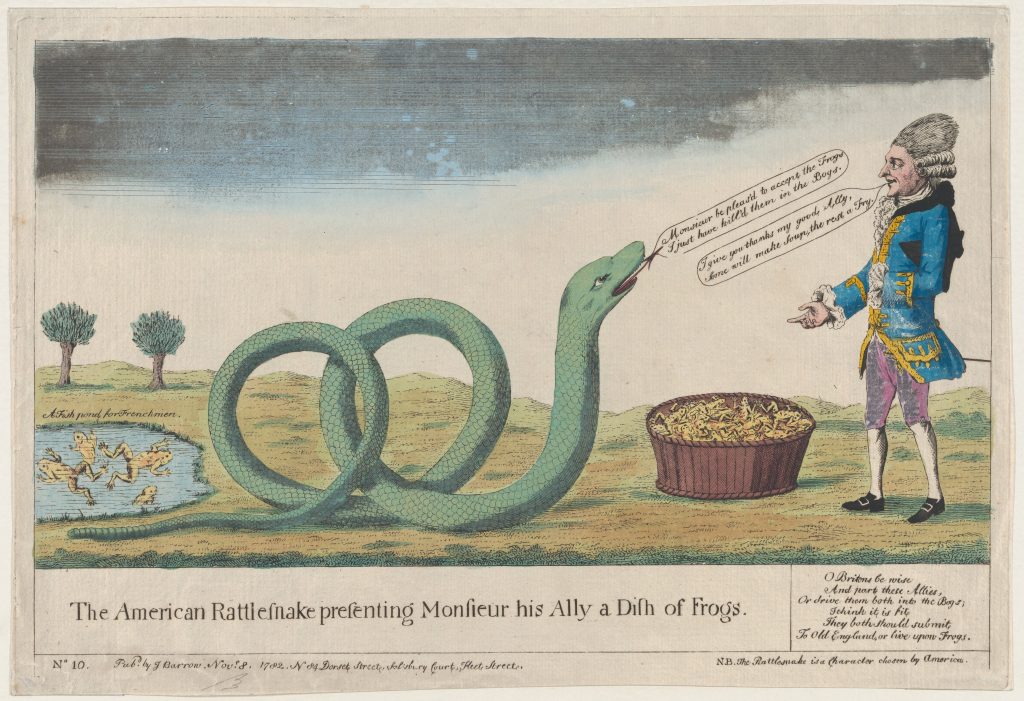

7. The American Rattlesnake Presenting Monsieur His Ally a Dish of Frogs, by j. Barrow, 1782 (English)

While the colonists used the rattlesnake to symbolize unity, self-defense, and resistance to oppression, the British focused on the snake’s biblical implications to paint the Americans as sly, treacherous, and evil.

This cartoon is an attempt to mock the Franco-American alliance, which came about in 1778 as a result of Benjamin Franklin’s diplomatic efforts.

The snake says “Monsieur be pleas’d to accept the frogs / I just have killed them in the Bogs.”

The unnamed Monsieur, portrayed as a stereotypical Frenchman, replies “I give you thanks my good Ally, / Some will make Soup the rest a Fry”.

Underneath the cartoon, a poem is written:

O Britons be wise

And part these Allies,

Or drive them both into the Bogs;

I think it is fit

They both should submit

To Old England, or live upon Frogs.

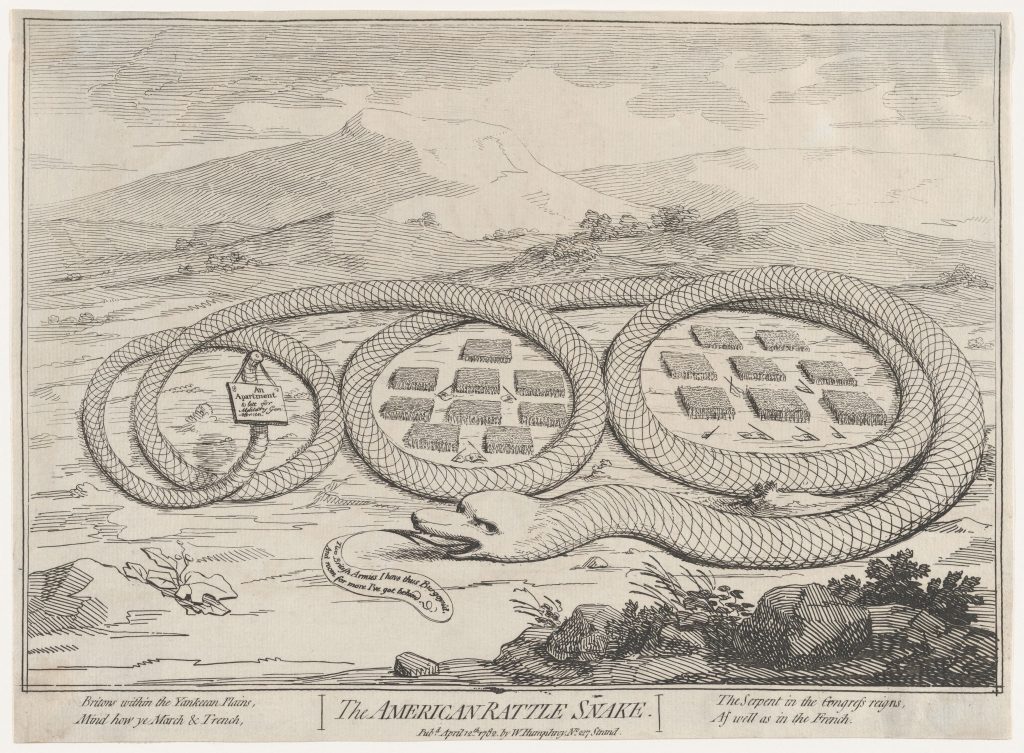

8. The American Rattle Snake by James Gillray, 1782 (English)

This cartoon shows British attitudes towards the conflict at the end of the war.

Gillray depicts the American rattlesnake encircling two groups of British forces, representing the armies of Burgoyne and Cornwallis, who surrendered in 1777 and 1781 respectively.

The snake says “Two British Armies I have thus Burgoyn’d, And room for more I’ve got behind,” and the flag on its tail advertises “An Apartment to lett for Military Gentlemen”.

Gillray is criticizing the lackluster performance of the British Army. The snake warns that remaining British troops should tread carefully, or they may also find themselves entrapped.

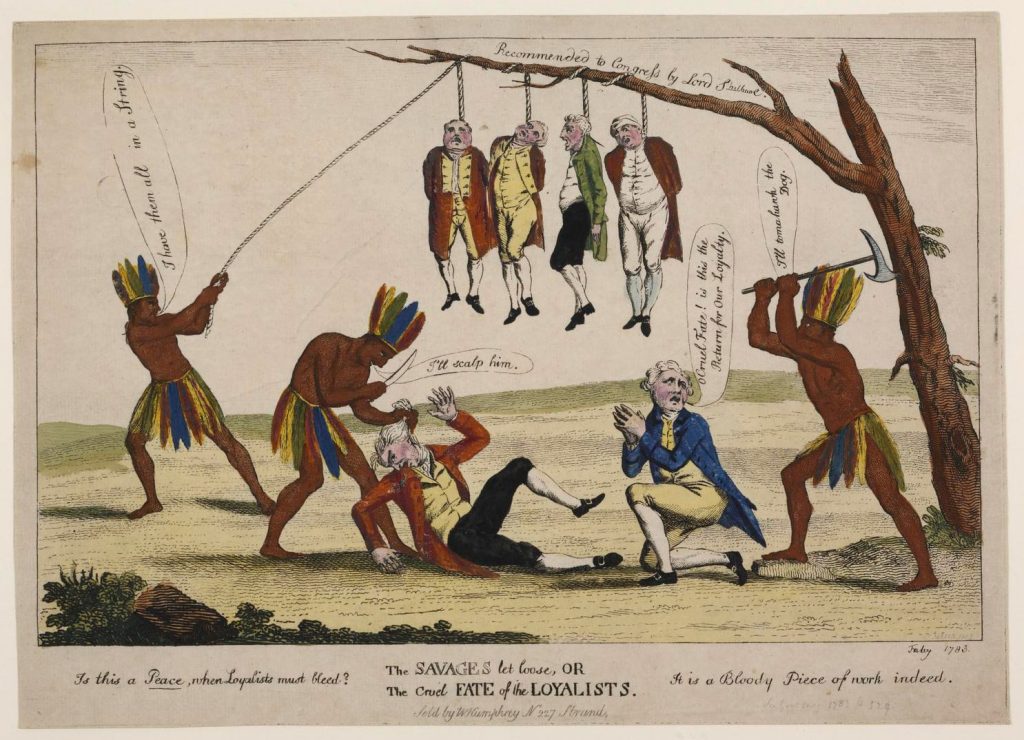

9. The Savages Let Loose by William Humphrey, 1783 (English)

After the American victory in the Revolutionary War, many Loyalists had their property confiscated, or faced mob violence. Many had to flee the country.

This etching paints the author’s view of the violence experienced by Loyalists after their defeat at Yorktown. It depicts the Americans as Native Indians, and shows them hanging and scalping white Loyalists. The inscription below the cartoon asks “Is this a Peace, when Loyalists must bleed?”.

According to most historians, Loyalists did experience violence and lived in fear after the war ended, forcing many to leave for Great Britain, Canada, and other countries. However, they did not face mass execution or violence to the extent the cartoon implies.