Contents

Contents

The government structure and political environment in the Middle Colonies varied from colony to colony, but generally emphasized greater levels of religious freedom and citizen participation compared to other regions of British North America.

Government structure

Pennsylvania and Delaware were proprietary colonies, meaning that they were governed by an individual or a company that was granted the land by the King of England. The proprietor appointed the governor and administered the courts, subject to English law and the king’s oversight.

On the other hand, New York was a royal colony from 1685, meaning that it was ruled and administered by the Crown.

East Jersey and West Jersey began as proprietary colonies under Quaker and other investors, but were united into the royal colony of New Jersey in 1702.

Colonial law was based on English common law, with local exceptions made by the colonial judiciary. Juries were a key component of colonial courts, for both criminal and civil trials.

The county was the primary local government unit across the Middle Colonies. County officers included the sheriff, coroner, justices of the peace, and road and tax officials. In contrast, the New England colonies generally ran local affairs through town meetings, while the southern colonies commonly used parish grounds for many local government activities.

Townships did exist in the Middle Colonies, mainly as administrative units for roads, and school and church matters, but with fewer powers than New England towns.

In New York, there were also separate manorial courts within large estates established by Dutch and English land grants. This meant that the lord of the manor could self-police their estate, especially in terms of petty disputes, such as issuing minor fines, creating local by-laws, and administering small debts.

Certain cities such as New York, Albany, and Philadelphia created their own municipal charters in the late 1600s, establishing mayors, common councils, and municipal courts. These charters also regulated markets, wharves, sanitation, street paving, and local policing.

Politics

Each colony was ruled by a governor, who represented either the proprietor(s) of the colony or the British Crown. Below them was the governor’s council, who advised the governor, and often sat as an upper legislative chamber, meaning that they reviewed, amended, or rejected bills passed by the elected assembly.

The elected assembly acted as a lower house, representing the local population, and was elected by popular vote – though only certain people could participate in elections.

The colonial governments were funded by property taxes, poll taxes (usually levied at a flat rate per-person, regardless of wealth), excises on liquor and trade, and court fees, among other smaller sources of revenue.

Elections

In each colony, only free males aged 21 years or older were permitted to vote. They also often had to meet other wealth-based requirements, which varied by region:

- New York: £40 freehold (land ownership). From 1777, £20 freehold or a rented tenement that cost at least 40 shillings per year.

- New Jersey: “£50 clear estate” (real or personal, meaning real estate, or personal property such as cash, livestock, or slaves) and about a 1-year county residency. “Clear” means that a person’s wealth must exceed £50 if they were to pay off all their debts.

- Pennsylvania: no fixed freeholds, must be a taxpayer.

- Delaware: similar to Pennsylvania in some areas, others required either 50 acres of freehold (with some under cultivation) or a £40 personal estate.

Candidates often had to meet higher wealth or land ownership requirements.

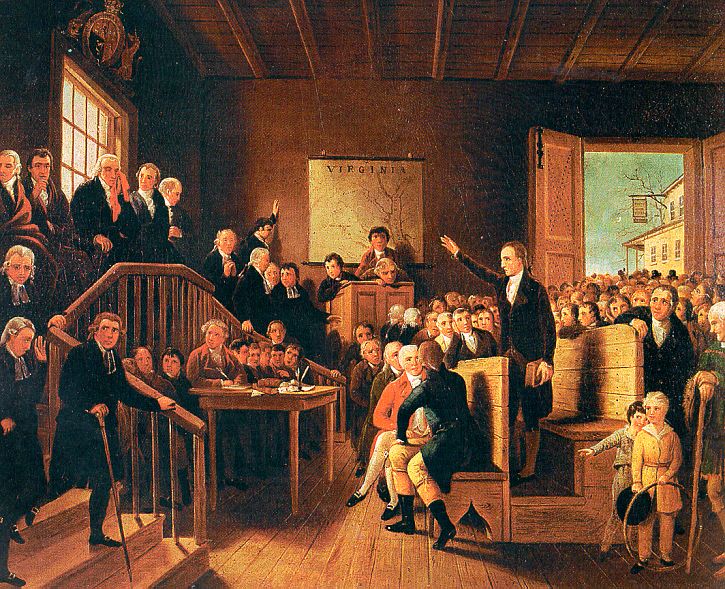

Votes were sometimes cast by ballot, especially in Pennsylvania and Delaware. In other colonies, voting was carried out orally and in public, with participants stating their choice in front of a crowd of onlookers and government officials.

In certain parts of the Middle Colonies, especially along the Hudson, this system gave the owners of large estates significant political power. They could carve out small plots of land and give them to loyal parties to effectively create voters, or deny freeholds to those who would vote against their interests.

The elected assemblies

The elected assemblies were very powerful, as they controlled taxation and government spending. They were known to sometimes make life difficult for the proprietor or governor, using their influence over financial affairs.

By modifying and amending laws, the assemblies could control colonial finances in line with electors’ interests, a mechanism that became known as “the power of the purse.”

For example, in New York, the assembly fought to keep the governor and other top officials’ salaries annual and conditional, rather than fixing them permanently. This meant that colonial officials had to constantly ensure they did not get on the wrong side of the elected assembly.

In Pennsylvania, elected politicians would withhold money until the governor agreed to ignore written instructions from the proprietors (the Penn family) that were deemed at odds with the colonists’ interests.

The situation in Pennsylvania became so bad that the assembly petitioned for royal government in 1764, in an attempt to remove the Penns from their position as proprietors.

However, when the British passed the wildly unpopular Stamp Act in 1765, followed by the Townshend Acts in 1767-68, the petition fizzled out, as Pennsylvania realized that the British posed an even greater risk to their liberties than the Penn family.

Separation of church and state

The Middle Colonies were unique in that they were much more tolerant of a wide range of different religions compared to most other areas of the Thirteen Colonies. This meant that political participation was open to people of different religious groups, rather than being restricted mostly to Puritans as was the case in most of New England.

Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey allowed politicians, jurors, and voters to affirm their loyalty to the colony rather than swearing an oath to God before performing their duty. This enabled Quakers to participate politically, as their principles forbade them from taking part in religious oaths.

There were also no mandatory parish taxes in most of the Middle Colonies, meaning that citizens did not have to fund a certain religious establishment in order to vote or hold most local offices. Though, New York did favor the Church of England in some counties.