Contents

Contents

Connecticut Colony, also known as the Connecticut River Colony, was founded by English settlers in America in 1636.

History

Founding

Massachusetts Bay was one of the first English colonies in America, after it was formally settled by Puritans in 1630.

After initially struggling to survive in the New World, the settlers soon established themselves, creating primitive farms and housing, aided in some cases by the Native American population.

Soon, the Puritans looked further afield for locations for new towns, with more room, and more fertile soil.

Connecticut was considered for settlement, but in the early 1630s it was thought to be too dangerous, due to the threat of the Pequot Indians and potential for Dutch retaliation, who had established a trading post on the Connecticut River.

By 1636 though, space was running out in Massachusetts’ main settlements. In June of that year, a group of around a hundred settlers led by pastor Thomas Hooker travelled to the site of modern-day Hartford, and established a town.

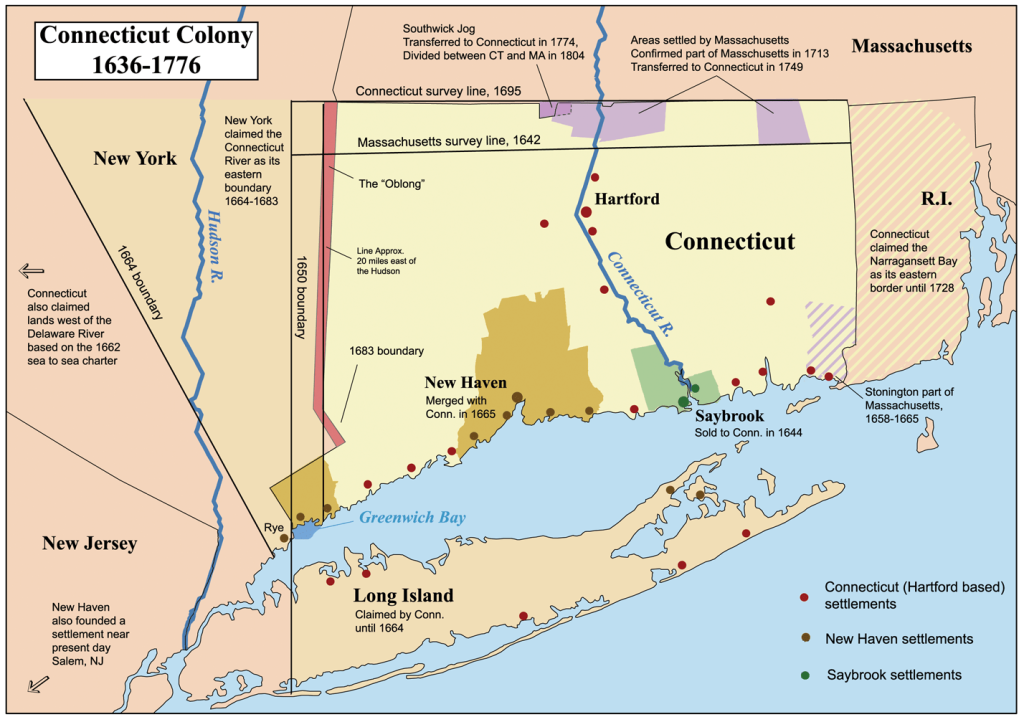

Though Hooker is widely considered the founder of Connecticut Colony, small settlements and outposts at Windsor and Wethersfield had already been established in 1633 and 1634 respectively.

In 1639, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut were signed, creating the first colonial constitution, and establishing the governance framework for the colony.

As outlined in the Orders, Connecticut was ruled by a governor – the first of whom was John Haynes – as well as an elected assembly.

Indian wars

In its early history, Connecticut was heavily involved in conflict against Native American tribes, especially the Pequot.

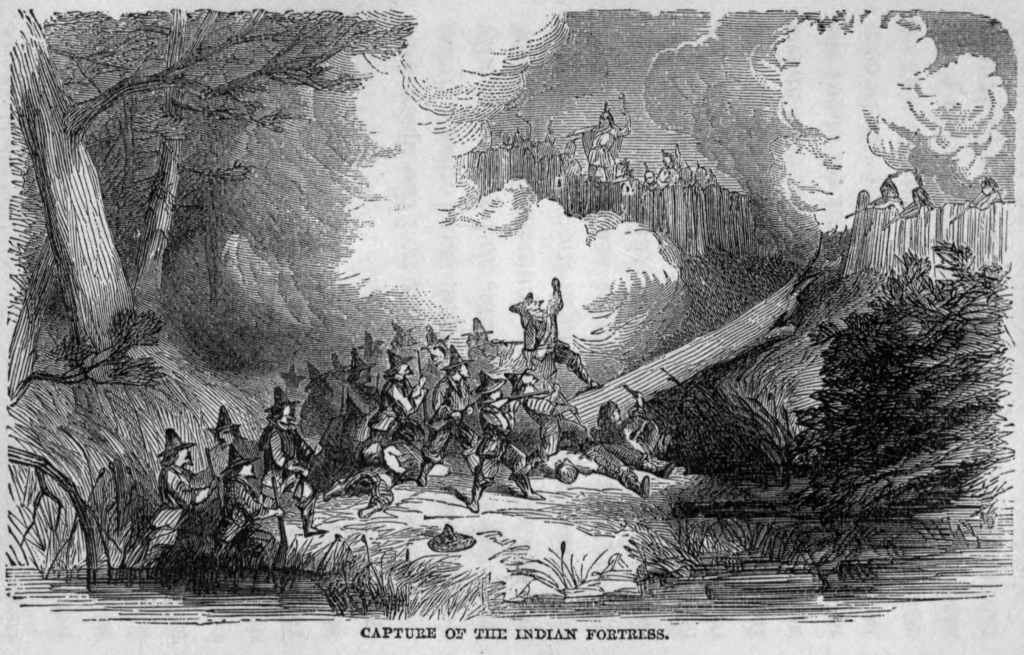

After an English settler named John Oldham was killed in July 1636, New England colonists attacked the tribes they believed responsible, beginning the Pequot War (1636-1638).

After massacring the Pequot near the Mystic River in Connecticut on May 26, 1637, killing or capturing 700 American Indians, the colonists continued hunting down the Pequot throughout Connecticut and New England, ending the war in short order.

Connecticut was also involved in King Philip’s War (1675–1676) between English colonists and an alliance of Wampanoag and other native tribes.

The war was devastating, killing thousands of colonists and Native Americans, and destroying significant amounts of crops and property. However, compared to elsewhere in New England, Connecticut was spared from most of the damage.

English relations

In 1662, Connecticut received a Royal Charter from King Charles II.

The Charter was quite liberal, similar to the one granted to the Rhode Island Colony. It gave Connecticut significant freedom to self-govern, and also defined quite expansive land claims, including the territory of New Haven – another English colony that never received a charter. Connecticut also now included the territory of the short-lived Saybrook Colony, which it had purchased in 1644.

In 1664, under the Connecticut Charter, New Haven was officially annexed by Connecticut, significantly enlarging the latter colony’s territory. Long Island, which was claimed by Connecticut at the time, was ceded to New York in the same year.

In 1686, the English Crown under King James II created the Dominion of New England, attempting to revoke the New England colonies’ charters, and uniting the settlements under the governorship of Edmund Andros.

The colonists resisted the Dominion, especially in Connecticut, as it threatened their rights to self-govern.

The British also tried to implement stronger trade and shipping controls, to raise revenue and encourage greater levels of trade with Great Britain. The colonists on the other hand wanted to retain the ability to trade with whoever they pleased, especially foreign colonies in the West Indies.

When Andros arrived in Connecticut on October 31, 1687, the colonists are said to have successfully hidden their charter in an oak tree, to prevent it from being seized. The tree later became known as the Charter Oak.

In 1689, following the Glorious Revolution in England, James II was deposed, Andros was overthrown, and the Dominion of New England collapsed.

Having saved its charter from being revoked or seized, Connecticut was able to immediately resume self-governance under its existing Royal Charter. The same could not be said of Massachusetts, which had to wait until 1691 for a new charter to be issued.

From this point on, Connecticut largely enjoyed the freedom to self-govern and trade with overseas territories under British salutary neglect, until the end of the French and Indian War in 1763.

Religion

Even though most of Connecticut’s early settlers were from Massachusetts Bay, where society and government were based on strict Puritanical principles, Connecticut was more liberal.

The colony was still based on a type of Puritan church governance structure known as Congregationalism, but religious dissent was more tolerated than in Massachusetts.

Voting rights in Connecticut were based on wealth and land ownership requirements after 1639, rather than being restricted to members of the church. However, all citizens had to pay taxes to the Congregationalist church, regardless of their religious beliefs.

Also, certain parts of post-1664 Connecticut Colony society held more extreme Puritan views.

New Haven Colony was initially established by John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton in 1638, in order to create a “Bible commonwealth,” with an even stricter religious foundation than Massachusetts Bay.

When New Haven was absorbed into Connecticut in 1664, its government was dissolved, giving non-church members the right to vote. However, local autonomy survived at the town level, meaning certain elements of hardline theocratic governance that existed in Connecticut’s former New Haven territories remained for some time.

Concerned with a growing lack of religious engagement, Connecticut civil and religious leaders consolidated the Congregational church system under the Saybrook Platform in 1708, setting up regional councils to oversee churches.

Over the next two decades, the elected assembly gave greater legal relief to religious dissenters, gradually allowing other denominations such as Anglicans greater freedom to practice their beliefs.

Economy

Connecticut had a mixed economy, primarily based on agriculture and maritime trade.

Initially, most settlers engaged in subsistence farming, before farms grew larger and the economy diversified as Connecticut matured.

The soil was suitable for agriculture in areas, especially in the Connecticut River Valley, allowing farmers to grow a wide range of different crops, including corn, wheat, and tobacco.

Over time, more farmers began to raise livestock such as cows, pigs, and sheep, and industries such as sawmilling, ironworking, and rum distilling began to take hold.

Apart from rum, the colony also produced smaller quantities of other goods such as lumber, preserved meats, and potash (a type of chemical used in the production of soap, glass, and other goods).

These goods were then exported to the West Indies and further afield through Connecticut ports such as New London and New Haven.

Though there was a strong shipbuilding industry in Connecticut, the colony’s main ports were not as busy as others in New England, such as Boston and Newport.

Many of Connecticut’s ports were too shallow for large ships to use, and the mouth of the Connecticut River was blocked by a high sandbar. Compared to colonies such as New York, Connecticut’s system of rivers and estuaries was not conducive to transporting large volumes of people or goods.

Slavery

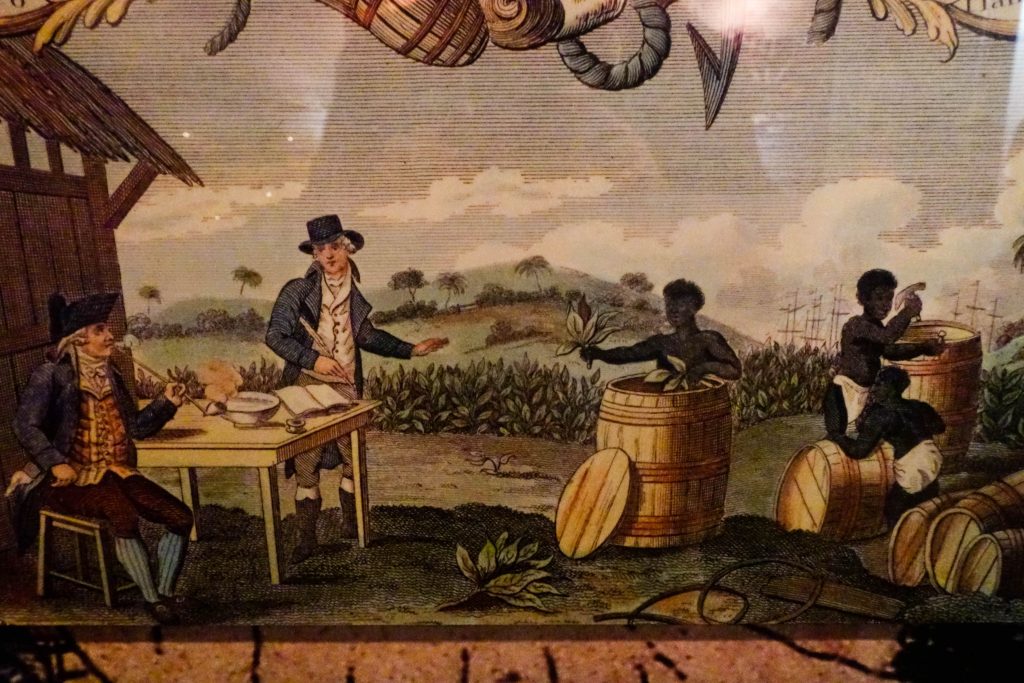

The Connecticut Colony had a long history of slavery, though it was not as pervasive as in the South.

As early as the Pequot War, Native American prisoners of war and civilians were enslaved, and used for household and agricultural duties.

Soon after, African slaves were brought into the colony, with some being traded for Pequot people.

Slaves worked in households, as well as on farms, and on docks and ports in Connecticut. New London was the center of the slave trade, where the majority of Africans were imported into the colony.

In 1784, a Gradual Emancipation Act was passed, stating that children born to slaves must be freed at 25. By 1790, there were about 5,100 slaves in Connecticut – about 3% of the total population.

Slavery was not abolished in Connecticut until 1848, making it the second-to-last of the New England states to officially do so (it took New Hampshire until 1857).

Facts

- Connecticut’s population was estimated at 1,472 in 1640, 75,530 in 1730, and 183,881 in 1770.

- Yale College was founded in Saybrook, Connecticut in 1701, originally to train colonial leaders and clergymen. It was called the Collegiate School until 1718.

- From 1647 to 1663, the Connecticut government executed 11 people who were found guilty of witchcraft, preceding the Salem Witch Trials by nearly 30 years.

- After the Pequot War, Connecticut, New Haven, Plymouth, and Massachusetts formed the New England Confederation to defend the region against threats from Native Americans, as well as French and Dutch settlers.

- During the American Revolution, Connecticut supplied a wide range of resources to support the Patriot cause, including men, food, and military equipment, giving it the nickname of the “Provision State.”