Contents

Contents

During its early history, Virginia was a predominantly Anglican colony, with the Church of England established as the official religion of the province.

Founding

Virginia was first settled in 1607 by Anglicans, a branch of the Protestant faith that was loyal to the Church of England.

Immediately, local churches were created, and this accelerated once the colony established itself and ensured its initial survival.

In 1619, the House of Burgesses was formed – the colonial government’s lower house – and in the same year, it formally established Anglicanism as the official religion of the Virginia colony.

In practical terms, this meant that:

- Taxes had to be paid to the local Anglican parish, no matter the resident’s religious denomination. There were no exclusions for religious dissenters (who followed other types of Protestantism), unlike in some other colonies.

- Church attendance was mandatory, and could be punished by fines.

- Each parish had a 12-man “vestry”, often made up of wealthy merchants or plantation owners from the local area. These vestries acted like a local government, with the power to hire and fire ministers, apportion funds to orphanages and social welfare programs, and enforce Anglican moral codes. Compared to most other colonies, Virginia was unique in that ordinary (though often very wealthy) people controlled the parishes rather than religious ministers or bishops.

Catholics and Quakers were subject to significant exclusions and discrimination, making it very difficult for them to live in Virginia during its early history.

For example, in the 1660s, fines were imposed on anyone who entertained a Quaker, attended a Quaker meeting, or possessed Quaker books or pamphlets.

Comparatively, the small number of Jews in colonial Virginia had an easier time, but were still effectively banned from voting or holding public office, because doing so required swearing an oath to the Church of England.

Virginia did not have a bishop. Instead, the Bishop of London had jurisdiction over the colony, and priests and ministers had to travel to England to become ordained.

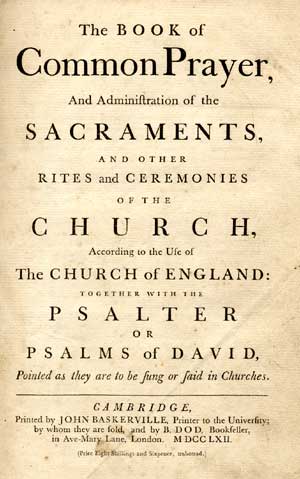

This, in part, led to a severe shortage of clergymen in Virginia, which often made it difficult for the Anglican ministry to organize services. At times, people were encouraged to worship at home using a guide to prayers and services called the Book of Common Prayer.

Anglican missions

Virginia’s first settlers also aimed to spread their religion among the Native American population.

The ministry wanted to reach the native populations quickly and spread Anglican ideals before missionaries from other denominations could. To do this, they planned to build schools, educating Native Americans to read so that they could study the Bible.

However, in the 1610s and 1620s, the Virginians were too focused on ensuring their colony’s survival to implement this plan. Later conflicts with Native populations and the Indian massacre of 1622 in Virginia led to the abandonment of most Anglican missions in the province, though some smaller native tribes and individuals did convert to Anglicanism during Virginia’s colonial period.

Later efforts by Anglican missionaries focused on enslaved African Americans, who predominantly worked on tobacco plantations in Virginia. These efforts were more successful by comparison.

18th century and increased dissent

In 1689, the Toleration Act was passed in England, which allowed people from other Protestant denominations to preach and worship in Virginia.

However, there were heavy restrictions on other denominations, and parish taxes still had to be paid to the Anglican Church, so Virginia remained a predominantly Anglican society throughout its colonial history.

Despite this, there was increased dissent and a slight increase in religious diversity in the Province of Virginia in the 1700s.

Presbyterians

Beginning in the 1740s, greater numbers of Irish and Scottish settlers started coming to the Thirteen Colonies, including Virginia.

The majority of these settlers were Presbyterians – another denomination of Protestantism.

Compared to Quakers for example, the Presbyterians were closer to Anglicans in terms of their beliefs, so they were not persecuted to the same extent.

Presbyterian migrants concentrated in certain settlements, especially around the Piedmont region. This allowed them to maintain influence over the church in certain areas through the vestry system, though they could not appoint Presbyterian ministers or significantly alter church services.

The Great Awakening and Baptists

In the 1730s and 1740s, there was a period of increased religious intensity and evangelical preaching in American Christian circles, known as the Great Awakening.

Through the mid-1700s, the effects of this movement drew people away from antiquated, strict Anglican services, which were often considered boring, and led them towards groups such as the Baptists, which were generally more progressive, with more evangelical, more exciting church services.

This led to increased religious participation and greater dissent against Anglican parish taxes, though they mostly remained in place until the American Revolution. The Baptists were particularly successful at engaging the slave population, converting many of them to the religion.

Despite their increasing influence, Baptists were still heavily persecuted in Virginia in the mid-1700s, with ministers occasionally jailed by Anglican-aligned provincial magistrates.

Methodist numbers also began to increase around the 1770s, but they remained a small minority in Virginia until after the Revolutionary War.

Lead-up to the Revolution

Conflict between Anglicans and Baptists was a problem for the Patriot movement.

Virginian Patriot leaders knew that they needed dissenters’ support in order to fight the British.

Therefore, mandatory parish tax contributions were ended in 1776 under Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, and the bill allowed for religious freedom in the colony.

The Anglican Church was eventually officially disestablished after the war was won, under Thomas Jefferson’s 1786 Statute for Religious Freedom.