Contents

Contents

The New England colonies were largely dominated by the Congregationalist Puritan movement, with a close connection between church and state, and little tolerance for religious dissenters.

The exception was Rhode Island, which was founded as a safe haven for different Protestant denominations and other religious groups.

Founding and early years

New England was first permanently settled by the British with the establishment of Plymouth Colony in 1620, New Hampshire in 1623, and Massachusetts Bay in 1630.

Plymouth was settled by Pilgrims, while New Hampshire and Massachusetts were settled predominantly by Puritans, and the same is true of Connecticut, which was founded in 1636.

The Puritans were a hardline sect of English Protestants who aimed to “purify” the Church of England. They wanted to remove perceived elements of other undesirable religious groups in the church, especially Catholicism.

They believed in complete devotion to the bible, morality, and church life, with a strong emphasis on the family unit and traditional gender roles.

The Puritan movement was especially hardline in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where Puritans came in their tens of thousands to build a model society based on these principles.

Compared to the other two initial New England settlements, the leadership of Massachusetts was the most strict and least tolerant of religious dissenters.

New Haven Colony was founded in 1638 as a “Bible Commonwealth,” and also had incredibly strict religious governance prior to merging with Connecticut in 1664. In saying this, post-merger, governance structures mostly remained unchanged at a local level, meaning this part of New England remained extremely conservative.

The Pilgrims in Plymouth Colony had a similar set of beliefs to the Puritans, but had separated from the Church of England entirely, rather than attempting to purify it. They were smaller in number and generally more accepting of religious outsiders compared to the Puritans.

While New Hampshire was Puritan-controlled, it was not set up as a model society in the same way that Massachusetts and New Haven were. Instead, the colony was intended as more of a profit-making venture for its proprietor, Captain John Mason.

Religious life in New England

In most areas of New England, society was largely organized based on religious principles.

The Congregational Church was the official religion of the colonies, and citizens had to pay mandatory taxes to help fund the church, regardless of their faith.

Religious dissenters (including other Protestant sects) were seen as a threat to society, and were often prevented from voting or running for office, though this was not the case in Connecticut or New Hampshire.

In more conservative areas such as Massachusetts, restrictions on non-Puritans were tighter, and religion affected many aspects of daily life.

- The government enforced religious law and strict morality, such as adhering to sabbath rules.

- Dissenters, especially Catholics and Jews, were effectively banned from the colony for their religious beliefs. Quakers were at times expelled, and some were even executed as dissenters in the 1650s and 1660s.

- Events that occurred in society were commonly seen as a sign from God. For example, if there was a poor harvest, this was seen as a sign that God was angry, and stronger devotion to Christ was needed.

Though church and state were closely linked, there were some levels of separation: church ministers could not hold elected office, for example.

Except for the enforcement of moral codes, the Puritans generally believed in limited governance. They thought that human beings had the potential to be sinful, and therefore government officials could overstep their authority if given too much power.

However, in Massachusetts, religion was used as the basis for lawmaking and justice. This was most famously illustrated during the 1692-1693 Salem witch trials, where 19 people were executed for practicing witchcraft, allegedly acting as agents of the Devil.

Rhode Island offers a moderate alternative

Roger Williams was a religious dissenter who was banished from Massachusetts Bay. A Puritan minister, he was expelled for arguing in favour of liberty of conscience and religious freedom in the colony.

In 1636, he moved west, purchased land from Native American tribes, and founded Providence as a safe haven for people fleeing Puritan religious persecution.

The new settlement was established with religious tolerance as a founding principle, and there was no official state church, unlike in the rest of the New England colonies.

Different religions could establish their own churches and worship freely, and were not required to pay taxes to other religious institutions. Religion and moral law played a much less important role in everyday life in Rhode Island compared to the rest of New England.

As a result, the colony quickly attracted settlers from a wide range of different religious groups, including Quakers, moderate Puritans, Catholics, and Jews. The first Baptist Church was established in the Thirteen Colonies in Providence in 1639.

Missionary efforts

New England was home to the most significant effort to convert indigenous populations to Christianity in the Thirteen Colonies.

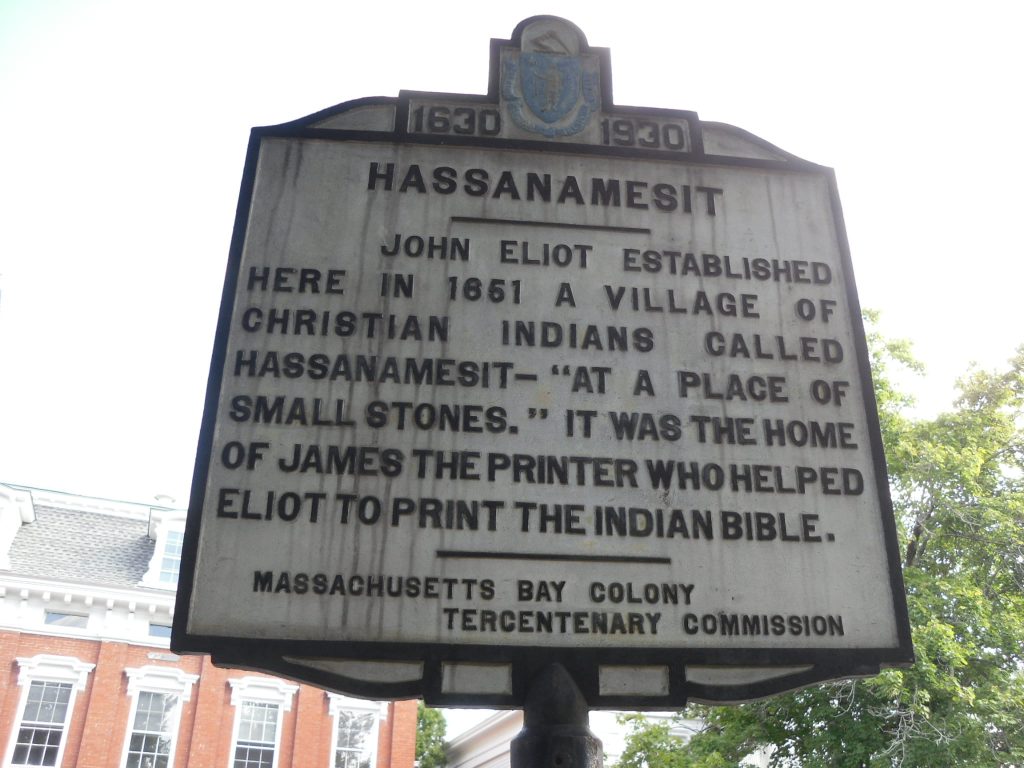

Beginning in 1646, small villages were created in New England known as “praying towns,” where missionaries would teach Puritan beliefs to Native Americans. These settlements were initially successful for the Puritans, converting large numbers of indigenous people to Christianity.

In total, there were 14 praying towns built in New England over the next 30 to 40 years.

However, during King Philip’s War between colonists and native tribes, which began in 1675, many of these towns’ residents were rounded up and interned, and the majority of the settlements were abandoned.

Congregational influence fades

Towards the mid-to-late 1600s, Puritan influence began to decrease in New England, for two main reasons.

The first was that as time went on, newer generations of Puritans were more moderate. They did not have the same level of dedication to traditional principles compared to those who made the journey from Europe.

This led to the implementation of the Half-Way Covenant in 1662, making it easier for people to meet the membership requirements of the Congregational Church.

The second was that at the end of the 1600s, the English began to restrict the power of New England’s Puritan governments.

First, the Crown attempted to consolidate control of the entire region under the Dominion of New England in 1686, undermining the Puritans’ governance structures, though this was short-lived.

Soon after, the 1691 Massachusetts Charter allowed the English to appoint their own governor of the colony, and permitted different Protestant sects – not just Puritans – to freely practice their religion, run for office, and vote.

The new charter also merged Plymouth into Massachusetts, ending the small settlement’s time as a separate region. From this point on, Pilgrims became an even greater minority in the Thirteen Colonies.

Towards the end of 1600s, greater numbers of Anglicans moved to New England, leading to greater levels of religious pluralism.

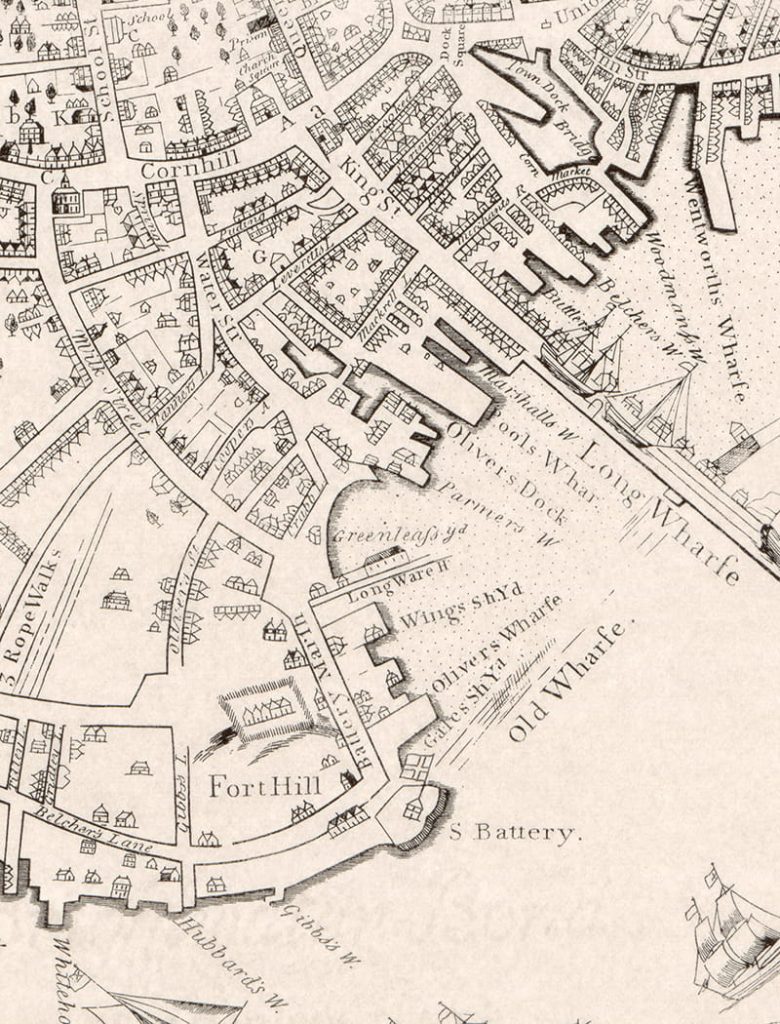

This was especially true as New England’s ports, such as Boston, grew into thriving Atlantic trade hubs. This brought in a diverse range of people into these cities, including traders, sailors, and merchants, as well as slaves, who practiced their own spiritual beliefs from their African home nations.

Despite this though, New England remained the most religiously conservative area of British North America throughout its colonial history, and the Puritan movement remained influential long into the 1700s.

The Congregational Church remained a strong force in Massachusetts and Connecticut in particular throughout the region’s colonial history. However, New Hampshire had greater levels of tolerance and pluralism, partly because its settlements were more spread out, making them harder for the church to oversee.

The Great Awakening

While the Congregational Church was influential throughout the 18th century, it became divided in the 1730s and 1740s as a result of the First Great Awakening.

This was a period of intense religious revival that spread throughout New England and the wider Thirteen Colonies around the early-to-mid 1700s.

Evangelical preachers traveled from colony to colony, challenging established church structures, and promoting a more free-spirited, individualistic style of worship.

Many aspects of the Awakening challenged the Puritan style of Christianity, which involved modest, traditional formats of sermon, and a much less emotional, more community-focused style of worship.

Despite this though, many members of the Congregational Church, especially younger populations, bought into the preachers’ messaging. This split the Congregational Church into “Old Lights,” who maintained the traditional way of doing things, and “New Lights,” who adopted a more evangelical, individualistic style of sermon and attitude towards religion.

1740s to 1770s

While the religious diversity of New England continued to increase over time, unlike the Southern and Middle colonies, the region did not experience large amounts of immigration from groups such as Anglicans, Scots-Irish, Baptists, and Lutherans in the 1700s.

Apart from the effects of the Great Awakening, the increase in pluralism in New England over time was largely due to internal migration between the Thirteen Colonies.

As New England’s governance became less theocratic, the region became more open to groups such as Baptists and Quakers, many of whom moved to the region to work in its ports and shipbuilding industries.

To learn more about religion in the New England Colonies, read our dedicated articles on this subject for Massachusetts and New Hampshire.