Contents

Contents

South Carolina was officially Anglican during the colonial period, and from the early 1700s, the Church of England was the official church of the colony.

However, South Carolina was settled and inhabited by a wide range of different groups, and was religiously diverse during the colonial era.

Founding and early years

South Carolina was initially joined with North Carolina as part of the Province of Carolina, established in 1663.

The land was granted by King Charles II to eight Lords Proprietors, who had helped the king return to the English throne three years earlier.

The Proprietors were predominantly Anglican, like the king. However, Carolina was founded primarily as a profit-making venture, rather than as a society based on specific religious principles (unlike the Massachusetts Bay Colony or Pennsylvania, for example).

Therefore, to begin with, Carolina was set up to be religiously tolerant in order to attract settlers to the new colony.

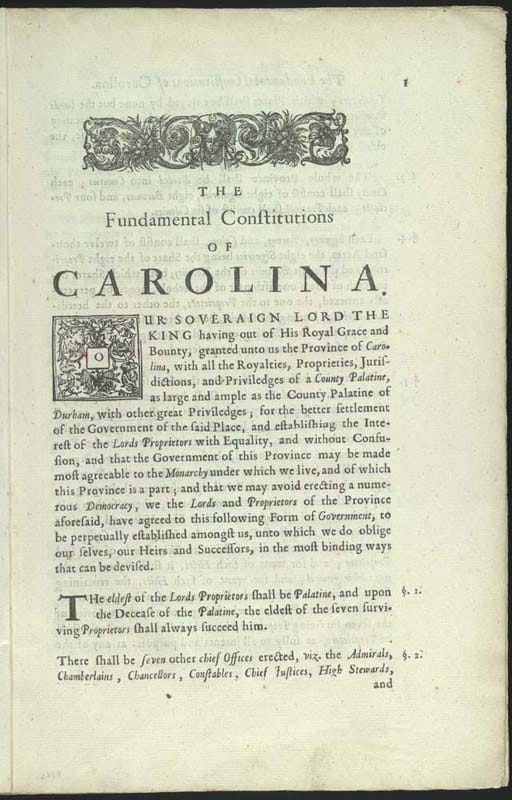

The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina (1669) established that “Jews, heathens, and other dissenters” were permitted in the colony, and that “any seven or more persons agreeing in any religion, shall constitute a church or profession, to which they shall give some name, to distinguish it from others,” effectively allowing for freedom of religion.

As a result, the first migrants to Charleston and South Carolina came from a wide range of different religious backgrounds. This included Anglicans, Quakers, Huguenots, and Jews.

Politically and socially, Anglicans and Quakers were the largest factions. Anglican parishes held a lot of influence, especially in the South Carolina Lowcountry.

Early 1700s: moving towards Anglicanism

By the beginning of the 1700s, Carolina was well-established, and was beginning to grow as a plantation colony. The population of South Carolina was estimated at 5,700 at the turn of the century, and by 1710, it had nearly doubled.

Large numbers of migrants were beginning to enter the colony, and settlers were moving west to find new areas to inhabit. In the backcountry, Scots-Irish Presbyterians were beginning to establish themselves.

It was at this point that Anglicans in Carolina tried to seize control of the colony, enforcing their own idea of how society should be run.

Under the 1706 Church Act, the Church of England was established as the official religion of Carolina. Parish taxes were implemented, requiring all people to fund the Anglican Church, regardless of their religion.

Anglican parishes were defined as the local government unit, and from 1716, Anglican vestries (parish leadership) became the only form of local governance in the colony.

Dissenters were denied public funding for their churches, and were also prevented from performing marriage ceremonies.

The new law also required politicians to swear an oath of office when being inducted into their roles. This effectively excluded Quakers from the South Carolina legislative assembly, as they were morally opposed to swearing an oath, instead preferring to affirm their truthfulness, without reference to God.

The Church Act was heavily influenced by English politics at the time, and aligned Carolina with the way things were done at home. England had recently undergone a campaign to remove dissenters from public office, which was spearheaded by Lord Granville, one of the eight Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina.

South Carolina still remained religiously diverse after the Church Act was passed, including after it officially separated from the North in 1712.

Dissenters and Jews were still allowed to vote and freely practice their religion after the Church Act was passed. However, due to ongoing conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Europe, and a fear of invasion from Spanish Florida, colonial leadership banned Catholic immigration to South Carolina in 1716.

There were Catholics in the colony, but they could not practice their religion openly, nor establish their own churches. Catholics were also effectively banned from holding public office in South Carolina, due to a requirement to swear an oath of loyalty to the British monarchy, rather than the Pope.

As a result, Catholics mostly kept to themselves and practiced their religion in private, and the number of Catholics in the colony remained very low over time.

Mid-to-late 1700s: the Great Awakening and increasing pluralism

In the 1730s and 1740s, a religious revival known as the First Great Awakening swept across the Thirteen Colonies, including South Carolina.

During this period, evangelical preachers traveled across British North America, promoting a radical, new style of Protestantism focused on liberty, individualism, and a more enthusiastic, engaging format of worship.

The effects of this movement were significant in South Carolina. Protestant groups split into New Lights, who embraced the new, evangelical style of religion, and Old Lights, who preferred more traditional, reserved religious practices.

Some members of the Anglican church moved towards Methodist and Baptist establishments, and the Presbyterian movement was split into New and Old Lights.

Many people who were previously “unchurched” began re-engaging with religion, and joined one of these Revival churches.

As a result, overall religious engagement in South Carolina began to grow, and pluralism also increased as members of other religious groups moved to the colony.

- The Methodist movement started in the middle of the century, fueled by the Awakening, before picking up in the late 1700s, predominantly in the backcountry.

- Similarly, the Revival led to the growth of the Separate Baptist movement, especially in rural parts of the colony. This sect originated from the Sandy Creek Revival movement in North Carolina, which began in 1755.

- The Jewish population increased slowly over time, and the first congregation was formed in Charleston in 1749.

- Numbers of Lutherans, who were predominantly German-speaking, began increasing from the 1730s, centered on a settlement at Purrysburg, in modern-day Jasper County.

- There were also settlements built by members of the Swiss and German Reformed Church beginning in the 1730s and 1740s. Many settled in the Saxe-Gotha Township in modern-day Lexington County.

On the other hand, after being excluded from politics, Quaker influence in South Carolina decreased during the 1700s. The sect still made up a significant proportion of the population, but their numbers declined as many moved to more tolerant colonies, such as Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

Despite its religious diversity, South Carolina continued to exclude Catholics from colonial life throughout almost all of the 1700s. The religion did not take hold in the colony until after the American Revolution, when restrictions were gradually lifted.

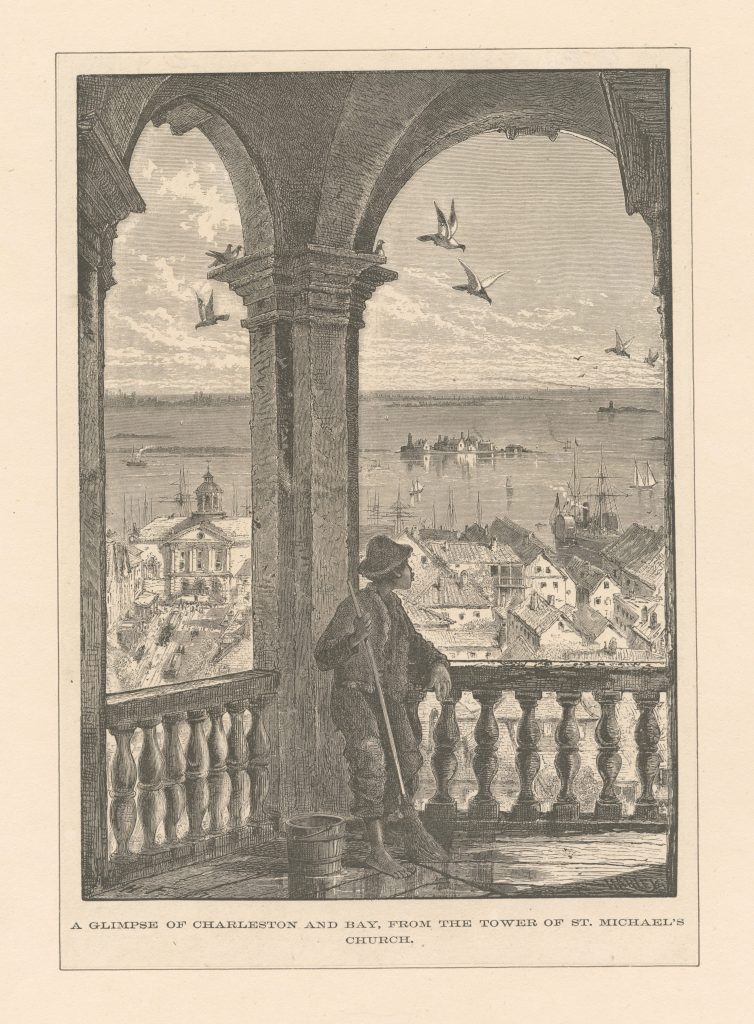

As the century progressed, South Carolina’s port cities, especially Charleston, became more developed, and more cosmopolitan.

These ports were trading hubs, populated and visited by merchants, sailors, and businesspeople from Europe, the Caribbean, and elsewhere in the Thirteen Colonies.

As a result, at the end of the colonial period, South Carolina’s cities were its most religiously diverse areas. While the backcountry and the rest of the colony also had members of many different sects, they predominantly stayed in their own small settlements, while some larger towns were dominated by one or two main religious groups.

Religion among slaves

By the mid-1700s, South Carolina was established as a plantation colony, powered by a slave labor force predominantly imported from Africa. In 1750, of the total estimated colonial population of 64,000, 39,000 were recorded as Black.

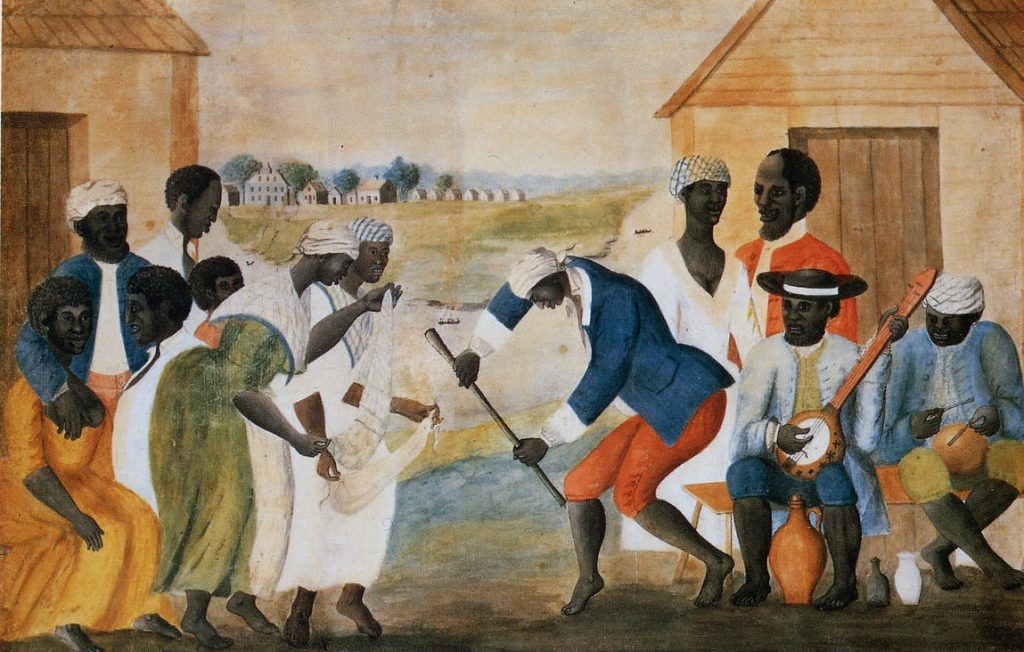

Slaves brought their own religious and spiritual beliefs with them from their homeland, and often continued to practice them in South Carolina.

At the time, West and Central African religion was centered around reverence for one’s ancestors; using magic, rituals, and herbs/natural medicines to promote spiritual healing and growth.

These elements were often combined with European influences to perform a type of religion known as hoodoo, which was commonly practiced by slave populations.

In some cases, slaves were dissuaded from practicing hoodoo, or were converted to Christianity, with many buying into the revival practices that came to South Carolina during the First Great Awakening. Gradually, as slaves began predominantly being born on the American continent, their religious practices moved away from hoodoo slightly, and more towards Christianity.

However, many plantation owners were wary of letting their slaves become Christian, especially as the revival movement began emphasizing the idea that all men were equal in the eyes of God.

Therefore, it was often the case that slaves were selectively taught specific aspects of Christianity that their masters believed would be beneficial, such as the importance of honesty and obedience.