Contents

Contents

In the sixth edition of “Les Caractères ” (1691), La Bruyè pronounced what we may call a funeral oration upon the fashions of the 17th century: “A fashion has no sooner supplanted some other fashion than its place is taken by a new one, which in turn makes way for the next, and so on; such is the fickleness of our character. While these changes are taking place, a century has rolled away, relegating all this finery to the dominion of the past.” La Bruyère might have added that fashion, like the phnix, rises from her own ashes, and that the supremacy of France, as the centre of fashions, was universally acknowledged – never more so than in the 18th century.

The moralists and philosophers, who set up to be the oracles of that age, never ventured to protest in very strong terms against the exaggerations and absurdities of dress, which they looked upon as a necessary, if not inevitable evil. The lawyer Alleaume, the imitator of La Bruyère, said in his “Suite des Caractères” that “The foolish set the fashions; the wise do not make themselves conspicuous by dressing in opposition to them. Ridiculous as certain fashions may be, it is still more absurd to studiously avoid their adoption.” Montesquieu (“Esprit des Lois”), while admitting that “fashions have their origin in vanity,” did not go so far as to condemn them altogether, as he considered them conducive to the commercial prosperity of the country. J.-J. Rousseau was even more severe on fashion, and on women who devoted most of their thoughts to it, for he declares that “an excessive love of dress is due rather to ennui than to vanity,” though he allowed that “costly attire proves social rather than personal vanity, for its use is solely a matter of habit.” He also allowed that the personal appearance of many women was set off by good dress, though he dogmatically added, “but none can require expensive finery.” Buffon, on the other hand, openly declared that “dress is a part of ourselves.” Voltaire was equally lenient in regard to fashions, but as he saw them continually changing, he denied that they were governed by good taste. In the “Questions sur I’Encyclopédie,” he argues that “taste is arbitrary in many matters, as with dress, jewellery, equipages, and everything that does not come within the domain of the fine arts; and in these cases it may more appropriately be termed fancy. It is fancy rather than taste which originates so many new fashions.” Whether fancy or taste, France had an almost complete monopoly of fashions during the 18th century, as was very cleverly shown by a celebrated caricature of the time of Louis XVI., in which the various peoples of Europe were represented with their national costumes. The Frenchman alone was naked, holding under his arm a parcel upon which was Written the following sentence: “As the latter is continually changing his tastes and fashions, we have given him the material, so that he can have it made up in the way he likes best.”

With all this, fashion had been almost banished from the Court during the last twenty years of the reign of Louis XIV., though it had found a refuge amongst the financial classes, and even with the wealthy representatives of the bourgeoisie, who were no longer under the subjection of sumptuary laws. These laws, often renewed and put in force from 1660 to 1704, had only been intended by Colbert as an indirect means of protecting French industry from foreign competition, one of the most stringent clauses being that which prohibited the use of all articles of apparel, such as English and Dutch laces, which were smuggled into the kingdom. However, whatever their object may have been, they were never strictly observed, and they soon fell into disuse, except so far as they related to the prohibition of stuffs into which gold or silver was worked. The decree of 1704 was the last ever issued in France with regard to female attire, and those which were promulgated in other countries were not any better observed than had been the case in France.

Male and female dress had undergone many characteristic modifications at Court since Madame de Maintenon’s moral influence had been so omnipotent with the King. The most marked change was in respect to the colour of the apparel, showy and variegated colours giving way to dresses of brown and sombre shades. Madame de Maintenon dressed like a penitent, generally wearing a large black coif upon the head, but as Louis XIV. had a great dislike for mourning, she wore dresses of some dark colour other than black, though even so her attire had a monastic look about it which harmonized with her general bearing and her manner. All ladies of her age copied her style, but the younger ones stood out as well as they could against these innovations. Thus they still wore as a head-dress the fontange (top-knot), which had been introduced in 1680, but they had effected several changes in its shape and style. St. Simon in his “Memoirs” satirically remarks: “The fontange was a structure of brass-wire, ribbons, hair and baubles of all sorts, about two feet high, which made a woman’s face look as if it was in the middle of her body. At the slightest movement the edifice trembled and seemed ready to come down.” The fontange had developed into this from a simple knot of ribbon tied in a knot across the forehead to keep up the hair which was brushed back to the crown of the head. In its perfected state, it was composed of pieces of gummed linen, rolled into circular bands, and used for keeping in place the bows, ribbons, feathers, and jewelled ornaments of this head-dress, which was also called a commode, while the various articles which were attached with pins to form the fontange were known by such eccentric names as the duchess, the solitaire, the cabbage, the collar, the musketeer, the palisade, the mouse, &c. The mouse, as we learn from a comedy by Regnard called “Wait for me beneath the elm ” (1694), was “a small bow of ribbon which is placed in the wood. I must tell you that a knot of frizzled hair which trims the lower part of the fontange is called the little wood.”

The fashion of wearing fontanges had lasted nearly ten years (which for a fashion is equivalent to a century) when Louis XIV., who had long conceived a dislike to these voluminous head-dresses, formally condemned them, Sept. 23rd, 1699, as is recorded by the Marquis de Dangeau in his diary. The Princesses and the ladies of the court obeyed without murmur, and though some of the elder ladies stood out for a short time, the example of the exiled Queen of England (the wife of James II.) led to their submission. St. Simon says The pyramids fell with amazing rapidity, and in the twinkling of an eye the ladies went from one extremity to the other.” By which he intended to signify that the new mode was to wear headdresses which laid quite flat upon the hair.

It was Mme. de Maintenon who introduced the use of falbalas (flounces), and even their abuse, for these flounces, plaited and slashed and puffed, which were so freely used for the petticoats and sleeves, made the dress look very heavy, concealing the good points as well as the defects of the wearer’s figure. Regnard, in his comedy already referred to, is as severe upon the falbalas as upon the fontanges, for he makes a valet in this piece say: “The Parisian ladies only invent fashions with a view of concealing their defects. The falbala corrects the imperfections of the waist and lower limbs, while the squinquerque (cravat) has been invented for ladies who have got a long neck and sunken throat.” But the falbalas lasted longer than the fontanges, which, left off at Versailles in 1699, did not entirely disappear in Paris till after the Regency. The falbalas were never given up, and the use of them was frequently carried to such an excess that a caricaturist of the Regency drew a sketch of a lady so enveloped in them that she looked like a turkey shaking its feathers and spreading out its comb. This caricature gave rise to a popular song called “La dinde aux falbalas,” but despite of both song and caricature, the falbala retained its popularity.

In many cases, the sudden discontinuance of a fashion was due to the most trifling circumstances; sometimes the Court set the example, and sometimes the town. Thus dresses looped up in front with knots of ribbon like window curtains, so as to show a rich petticoat made of some different material and trimmed with circular bands laid one above the other, were still worn at Court, long after the fashionable ladies of Paris had abandoned them for the andrienne, so called after Baron’s comedy (Nov. 6, 1703), in which Marie Carton Dancourt appeared in a long dress with a low body. Such a dress was too “fast” for the Court of Louis XIV. and Mme. de Maintenon, and, moreover, the brocaded stuffs, with their and arabesques, which were exclusively used for Court dresses, would have been too stiff and heavy for the andriennes, which were required to be made of silk or light satin, so that they might undulate gracefully at the least motion. It is true that the young Princesses and the ladies of the Court who were of about the same age, encouraged by the example of the Duchesse de Bourgogne, revolted against the ancient modes, and occasionally dressed after the new ones originated in Paris, but not on state occasions, when the rules of etiquette could not be transgressed in the smallest particular.

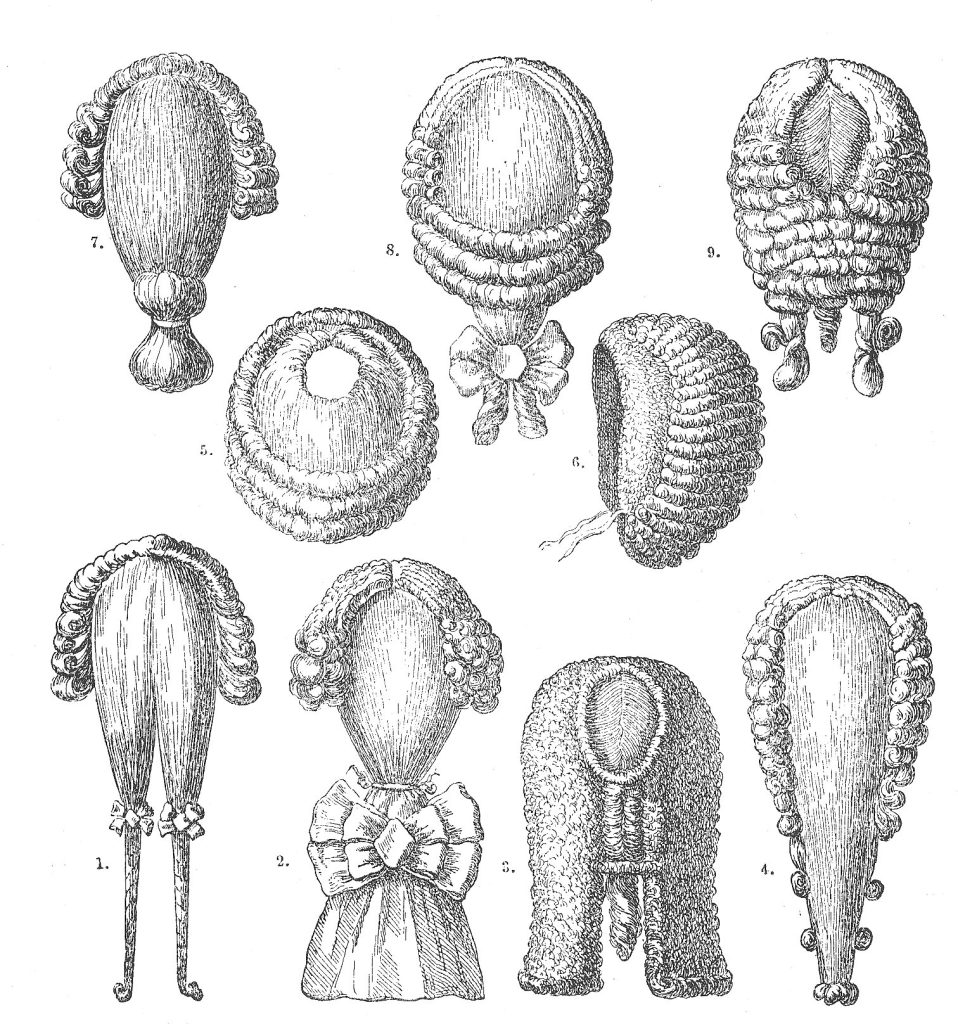

The King himself, absolute as his authority was, was compelled to submit, in some things, to the exigencies of fashion. He continued to wear his enormous wigs when the dimension and the shape of wigs changed. This almost universal change was brought about by the perfumed starch powder which men used for their false hair. In this instance, it was the old who set the fashion instead of the young, and only powdered wigs were worn for the future, whether the hair of which they were made was dark or light. Louis XIV. at first denounced the use of powder very vigorously, but he was assured that it modified the effects of age and softened the expression of the face to which the black wig imparted a hard and forbidding air. He allowed himself to be persuaded into the use of powder, but he would not alter the shape of his wigs, though the gentlemen of the Court had brought into fashion several new kinds: the cavalière for the country, the financière for the town, the square wig, the Spanish wig, etc. People even wore horse-hair wigs, which did not uncurl when exposed to the air. But powder was the special attribute of the dandies, who never appeared in public without being powdered down even to their justaucorps. Everybody rejoiced in a white head, and one courtier ventured to remark to Louis XIV.: “We all wish to appear old, so as to be taken for wise.” Powder led the way to the reduction in the size of wigs, from beneath which gradually emerged the natural hair, powdered and pomaded, gathered up at the back of the neck with a piece of black ribbon, and enclosed in a net which fell upon the coat collar.

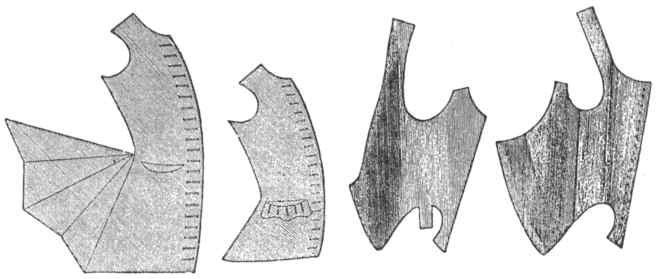

The fardingales of the 16th century reappeared at Court under the name of panniers, and they tended to increase the volume of petticoats and dresses which, narrowing from the waist downwards, took the shape of the round hoops, made either of whalebone, cane, or pliable wood, over which they were worn. The panniers, which were not preposterously large at first, imparted an air of dignity to Court dresses, and added grace to dresses with long trains; but the wives of the financiers and of the bourgeois, as soon as they got hold of the new fashion, carried it to excess. The panniers assumed such monstrous proportions that, to borrow the expression of a satirist, they made short women look like balls, and tall ones like bells. The hoops, or criardes as they were also called, did not displace the falbalas and flounces which, on the contrary, were used for every part of the dress. It was in vain that the critics and caricaturists waged war upon a fashion which caused obstructions at the theatre, in the drawing-room, on the public promenades, and especially in a carriage. But the ladies did not give way before this coalition, and the panniers lasted, with certain modifications, until the reign of Louis XVI. Of all shapes and sizes, they were an indispensable part of the dress, even when the wearer was in the most negligée toilette. The ladies also increased the volume of their petticoats by the use of bustles, and it was about this time that Chevalier d’Hénissart published two or three very severe satires upon the women of the bourgeoisie who indulged in such extravagance of dress (1713). The fashion of wearing panniers was also held up to ridicule, though without effect, in a comedy played before the young King (Louis XV.) at Chantilly, on the 5th of Nov., 1722, and the size of the panniers continued to increase. The Nouvelliste Universel of August 21st, 1724, describes them as follows: “They are linen bells, kept in place by whalebone hoops;” and the same newspaper follows up the attack by enumerating the inconveniences which they caused in all places of public resort. The reign of Louis XIV. once at an end, and Mme. de Maintenon’s black coif ceasing to cast its shadow over the Court, bright colours and stuffs of light material soon made their reappearance, and the dresses were made with a profusion of trimmings called prétentailles, numerous flounces, short open sleeves with engageantes, which had a treble row of embroidery, lace, guipure, ribbons and bows of all kinds. Amongst the curious names given to the various inventions of the fashionable dressmakers, we find guenpes (sic), fard, postiches, boute-en-train, jardinières, coiffures à la culbute, galante or à la doguine, nonpareilles, abbatans, rayons, maris, colinettes, crémones, sourcils de hanneton, mousquetaires, souris, battans, pouce, battans l’il, assassins, suffoquans, favoris, bouquets, bagnolettes, etc. (1724). This multiplicity of names for dress trimmings and head-dresses shows that the Regency, in encouraging everything in the way of pleasure and luxury, had inaugurated the reign of the coquettes. Dufresny declared in 1703 (as he might have done with still greater truth in 1715): “The contempt which women of high reputation profess for the coquettes does not prevent them from imitating these latter. They dress after them, and catch their way of talking. One must swim with the stream. The coquettes invent new fashions and new modes of speech, and they are all in all. He also compared women to birds who change their plumage two or three times a day, but this was moderation itself compared to the customs in 1746, when all fashionable ladies endeavoured to change their dresses four or five times at least. There was the morning toilette or négligée, the walking toilette, the theatre toilette, the supper toilette, and the night toilette. the last-mentioned not being the least sumptuous and complicated. The most singular vagary of fashion, the use of patches, was indulged in to such an extent that, as a contemporary critic declared, women’s faces looked like the signs of the zodiac. The patches of black silk were, in fact, cut into the shape of a moon, sun, star, comet, and crescent. They had been used in the time of Louis XIV to set off the whiteness of the skin, but only sparingly, and ladies of dark complexion took care not to put them on. They had almost died out of use when the Duchesse du Maine brought them into fashion again, and, thanks to her example, they came to be looked upon as the distinctive. sign of a beautiful skin and an indispensable accessory to the play of feature, retaining their vogue until the middle of the reign of Louis XV. It required a special knack to place these patches where they would best set off the face – upon the temples, near the eyes, at the corners of the mouth, upon the forehead. A great lady always had seven or eight, and never went out without her patch-box, so that she might put on more if she felt so inclined, or replace those that might happen to come off. Each of these patches had a particular name. The one at the corner of the eye was the passionate; that on the middle of the cheek, the gallant; that on the nose, the impudent; that near the lips, the coquette; and one placed over a pimple, the concealer (receleuse), etc. The masks, which the ladies of the 17th century employed less to hide their faces than to protect them from the sun and the wind, were no longer in use, except on certain delicate occasions when a lady did not wish to be recognised, either on horseback or in her carriage. But they were always taken off before going into a room where the lady who had been wearing the mask would meet persons of a rank superior to her own.

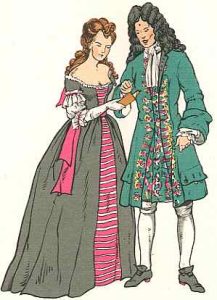

Though men’s dress had undergone fewer changes than that of women since the time of Louis XIV, it had lost a good deal of its heaviness and affectation; but fashion still delineated the characteristics of the time. The large coat embroidered with gold was still worn at Court ceremonies, sometimes open in front and sometimes buttoned up, with swordbelt or waistband; while the large wig, not yet powdered, flowed down over the back and shoulders. In private society, the coat was not so heavy and fitted closer to the figure; it was, moreover, shorter, and the sleeves were tighter. It was extended in the back by the insertion of whalebone, and had a double row of silk or metal buttons, which varied in shape and size according to the fancy of the day. In 1719 these buttons were so small that, at a comedy called “La Mode” (Théâtre-Italien) they were represented as having been made so diminutive that it required a microscope to discover them. The waistcoat, cut low in front, displayed the frill of lace or embroidered muslin and the cravat made of the same material. The breeches were no longer the plaited trousses, or voluminous canons, which formerly fell in folds over the white silk stockings. They were worn very narrow and led the way to the use of the eighteenth century breeches. The polished-leather shoes had very high heels and covered the instep. The nobles, the gentlemen and the Court people wore, as a distinctive mark, shoes with red heels.

If men’s fashions did not change very much, they were none the less very expensive. The Duc de Villeroy, on paying a visit to the Czar Peter I., in his capacity as governor of the young King (1717), had a coat embroidered in fine gold, with designs of various kinds of fruits and leaves. The Marquis de Nesle, who had sought the honour of being sent to meet the Russian Monarch on his arrival in France, started on his mission with an immense wardrobe of Court dresses, wearing a fresh one every day. Peter I. did not appreciate this delicate compliment, for he remarked to a courtier: “I am really very sorry that M. de Nesle has got such a bad tailor that he cannot find a single coat to his liking.” Twenty-seven years after this, the Court dresses were just as magniificent and even more expensive. Upon the arrival of the Infanta of Spain, Maria-Theresa-Antoinette, who had just been married to the Dauphin (1745), the costumes were so costly that many people hired them instead of purchasing them. Barbier states that the Marquis de Mirepoix paid his tailor £240 for the use of dresses which he only wore once. The Marquis de Stainville, the Envoy of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, ordered for the entertainments at Versailles a coat of silver cloth, embroidered with gold and fined with sable, the lining alone costing £1,000. This excessive expenditure was often encouraged, where it was not absolutely enjoined by the King himself, and Barbier, writing in December, 1751, states that the courtiers launched into the most reckless expenditure on the occasion of the fêtes given to celebrate the birth of the Duc de Bourgogne. “The King has let all the gentlemen and ladies of the Court understand that they must appear in gorgeous dresses, and not in plain black velvet. This led to a heavy expenditure. The Duc de Chartres and the Duc de Penthièvre were the most richly attired, the button-holes of their coats being sewn with diamonds; the other guests were dressed in gold materials of great price, or coloured velvets embroidered with gold or trimmed with Spanish lace.”

The magistracy and the higher bourgeoisie clung as long as possible to a simple and modest mode of dress, and Duclos records in his “Memoirs,” written about 1740: “Thirty years ago you would never have seen a pedestrian dressed in velvet, and M. de Caumartin, Councillor of State, who died in 1720, was the first gentleman of the long robe who adopted this custom . . . While the highest branch of the magistracy displayed so much modesty, the financiers could not well be ostentatious, and even the wealthiest of them lived very quietly. I have seen some of them who were content with a plain carriage, lined with brown cloth, such as Serrefort recommends to Madame Patin in the comedy of ‘Le Chevalier à la mode,’ (played in 1687) . . . In earlier times luxury of all kinds was not procured for money, for in some forms it was a mark of social superiority.” Thus the bourgeois dressed in accordance with their rank, wearing stout cloth, rateen or barracan according to the season, though, however the material might vary, it was invariably of a dark colour. They wore small wigs, either round or square, which were not frizzled, and to which powder was applied but sparingly. Their shoes were plain and thick-soled, and they wore stockings of black or grey wool, with the garter buckled below the knee. The female members of the bourgeoisie wore, with few exceptions, plain woollen or cotton dresses of some neutral shade, without any ribbons, or embroidery, or lace. The only item of costume which they took from the Court fashions was the pannier, which was universally worn. But dress soon ceased to be a distinctive sign of the wearer’s rank and profession, and Barbier complains in 1745 that money counts for everything in Paris, and that the middle-classes cannot keep their place.

The lower-classes, both in town and country, notwithstanding the daily changes of fashion which they saw going on around them, had not changed, in regard to dress, for the last century or two. They were poorly clad, in winter as in summer, but poorly provided with linen, and often going about with naked feet, but never without a covering to the head. Their garments often consisted of pieces of cloth of different colours sewn together, forming a coat which sometimes fell below the knee. They did not seem to feel this penury of raiment at all keenly, for the Marquis de Paulmy, in his “Précis de la Vie privée des Français” (1779), says: “Stout leather shoes are looked upon as a luxury by the poorer classes, who think themselves fortunate when they have shoes with thick soles. In some parts of the country, the peasants wear nothing but sandals, clogs, or pieces of rope wound round the feet, and in others men and women alike wear the sabot” (wooden shoe). Such contrasts, such striking anomalies between the dress of the lower orders and the middle-classes, were not to be seen in Paris and the large cities, where the poor dressed in the left-off clothes of the rich. The result, of course, was that the same clothes were worn in course of time, first when they were new and afterwards as they were old, by the two extremities of the social body. This was one of the most remarkable peculiarities in Parisian life “Everybody is well clad there, and seems as if he could afford to change his linen and coat twice a day.” Most Of the artizans dressed in imitation of their betters when they were not at work, and it was no uncommon thing to meet in the streets a lot of dandies, fashionably dressed and girt with a sword, who turned out to be barbers, printers, tailors, or shopmen. The females of the lower classes were always neatly dressed, sometimes with remarkably good taste, and the Paris grisette was renowned throughout the whole of the 18th century for her neatness of attire. Gorgy, in his “Nouveau Voyage Sentimental” (1785), says: “The girls employed in shops of various kinds aspire to be classed above the lower ranks of the people; their dress is plain and yet comely, and amongst them may be studied that sort of coquetry which Rousseau declares to be inherent in the female nature. It does not consist of a lot of gew-gaws which are but advertisements of the wealth of their wearers and the skill of their makers. These women wear only inexpensive dresses, with a little gauze and a few bits of ribbon, but they make the most of them, and produce considerable effect out of very little. Their coiffure is very simple, but it suits them so well that it seems perfect.” This corresponded very closely wi th J.-J. Rousseau’s opinions, for, in “Emile,” he writes : “Give a young girl who has good taste and sets little store on the fashion of the hour, some ribbon, gauze, muslin, and flowers, and she will make, without the aid of diamonds, lace and trinkets, a head-dress which will suit her a hundred times better than all the jewellery of Duchapt could do.” But a young girl who was capable of doing this would not have run counter to fashion.

The Marquis de Caraccioli in his “Voyage de la Raison” (1762), says: “To be in Paris without studying the fashions is to go about with one’s eyes shut. The squares, streets, shops, carriages, people, the whole place is full of them . . . When a fashion is first brought in, the capital goes mad over it, and nobody ventures to appear in public without it.” One of the fashions most in vogue during the reign of Louis XV. was the mode à la grecque, which, in reality, was a single name given to many objects totally dissimilar. First of all there was the coiffure à la grecque, a way of dressing the hair that had nothing of the ancient or modern Greek about it, for the hair, crumpled and gathered into a knot, was covered with a lace cap bristling with feathers and flowers. The name was afterwards applied (in 1764) to all articles of attire, and even to shoes. This fashion probably originated in some theatre, where it was doubtless introduced by the reigning actress. The modes, previous to this designation, were à la Ramponneau, and this name was derived from the celebrated guinguette of La Courtille. As a general rule, a name had no connection with the fashion which it was made to designate. For instance, the following is the description of the costume à la Joan of Arc, which the ladies of the Dauphine (Marie-Antoinette) were unable to bring into fashion even at Court: “Dress à l’austrasienne, a sort of polonaise very open in front over this a vest à la Péruvienne, surmounted by a contentement similar to the bows worn on sabots; trimmings round the collar of a demi-Medicis shape; Cretan cap, trimmed with flowers.”

The male costume à la Henri IV. for men did not fare any better, though the leaders of fashion, at the request of the Compte d’Artois and Marie-Antoinette, endeavoured to introduce it, as a Court-dress, at the private entertainments given by the Princes of blood. The Comte de Ségur, who took part in them, says: “This costume was well enough for young men, but it did not at all suit middle-aged men, especially if they were short and inclined to corpulence. The silk mantles, the feathers, ribbons, and brilliant colours, made them look ridiculous.”

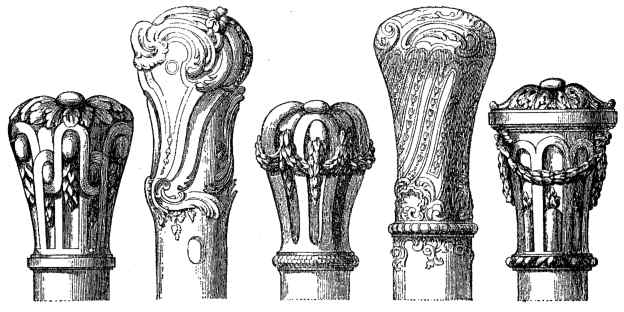

The two sexes seemed to compete with one another in fashionable matters, and, as a general rule, a name given to some article of female dress eventually came to be used for male attire. After the marriage of Louis XV. with Marie Leczinska (1725) the fashions were all à la polonaise. The campaigns of Hungary and Germany led to the introduction of hongrelines, which had been in vogue a century before. The marriage of the Dauphin to the Infanta of Spain (1745) led to a revival of Spanish fashions, which had never entirely died out at the French Court, where they had so often enjoyed high favour. Thus, in 1729, there was a revival of mantillas, not only in black and white lace or other light stuffs, but in velvet, satin, and even in fur. These mantillas were not worn upon the head, but the two ends were tied across the waist. The toilette of ladies who followed the fashions was completed by many accessory objects which were held to be indispensable to the dress of a lady of good condition or of bon ton; as for instance, trinkets, watches, caskets, fans, and even canes. Men had always carried canes, which were made of bamboo, ebony wood, &c., with the head made of metal or some other substance. The long gold-headed cane, once called cane à la Tronchin and afterwards à la Voltaire, was chiefly used by elderly men, magistrates and dignified personages.

The pliant canes, varying in length, were only suitable for young men in easy morning dress (en chenille). The younger ladies eventually took to using the long gold-headed cane, which they held in the middle, like the suisse at the door of a nobleman’s residence. This led to the introduction of very costly canes made of scented wood, tortoise shell and ivory.The fans, which were at first used for fanning, eventually became more ornamental than useful, and the commonest were made of scented wood, while the most expensive were of tortoise shell and ivory, incrusted with ivory and precious stones, and painted by artists of great talent. The pocket handkerchiefs, which were very small and were made of valuable lace embroidered with gold and coloured silks, also ceased to be more than a mere set-off to the whole costume.

The reign of Louis XV. gave a wonderful impulse to two branches of trade, which were looked upon as fine arts, viz., the boot and shoe trade and that of the coiffeur. The ladies’ shoe-maker was almost an artist, for he made such small shoes in every colour of leather, set off with gold and silver embroidery, and with high narrow heels, that they were the most elegant part of the whole dress. The price of these luxurious shoes with their buckles in gold or cut steel, was as great as that of many articles of jewellery. The prince of shoe-makers at that period was, thanks to the patronage of the Comtesse du Barry, a German called Efftein, who was succeeded by a Frenchman of the name of Bourdon. Men’s shoes were also ornamented with buckles carved and chased.

The fashions in head-dresses varied even oftener than those in shoes, and the number of ladies’ hair-dressers increased so much, that there were no less than 1200 of them in Paris in 1769, when the corporation of wig-makers proceeded against them for exercising their trade without due authority. The advocate of the persecuted hair-dressers published the following laughable protest in defence of his clients: “The art of dressing a lady’s hair can only be attained by a man of genius, and is consequently a liberal and a free art. Moreover, the arrangement of the hair and the curls is not the whole of our work. We have the treasures of Golconda in our hands, for we arrange the diamonds, the crescents, the sultanas and the aigrettes.” Having thus described his clients, he proceeded to demolish the master wig-makers, whom he thus caricatured: “The wig-maker works with the hair, the coffeur on the hair. The wig-maker constructs artificial hair, such as wigs and curls; the coiffeur merely arranges natural hair to the best advantage. The wig-maker is a tradesman who sells his materials and his work; the coiffeur merely sells his services.” The coiffeurs won the day, and one of them, Legros, founded an Academy of Hair-dressing, and published a large illustrated book called “The Art of Hair-dressing for French-women.” Another hair-dresser and rival of Legros, one Léonard, conceived the idea of substituting for the cap generally worn pieces of gauze and other light material artistically folded in the hair, and he succeeded in placing fourteen ells of gauze in a single head-dress. He was the fashionable hair-dresser when the young Dauphiness set the seal to his reputation by patronizing him. Marie-Antoinette had a regular hair-dresser called Larseueur, who was the reverse of clever, and though so good-natured that, rather than dismiss him, she allowed him to do her hair regularly, he had no sooner completed his work, than Léonard came to undo all he had done, and build up a new edifice.

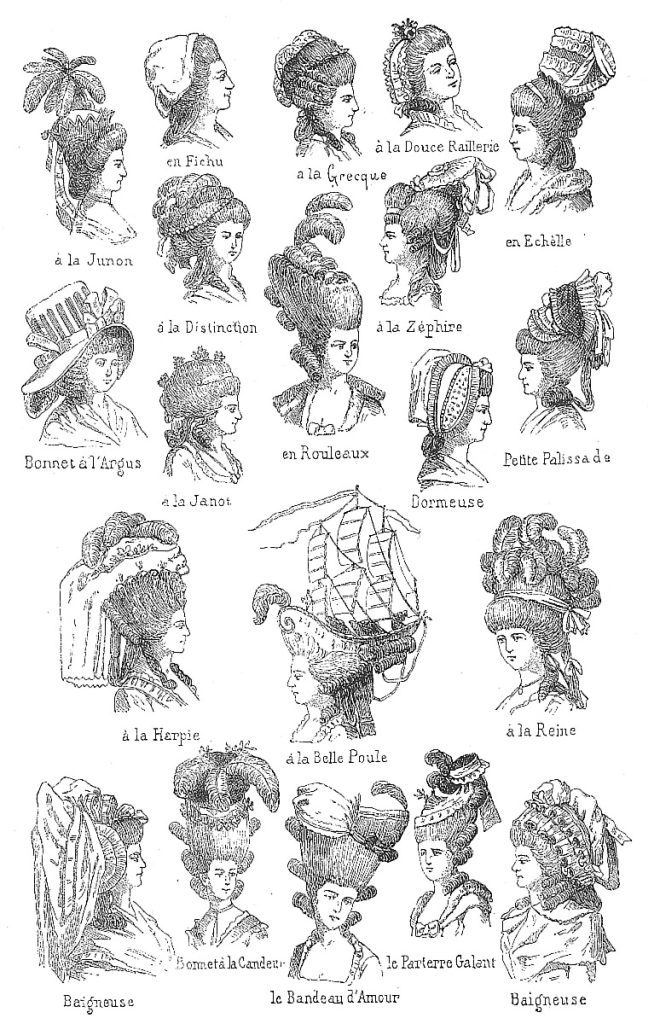

Léonard was the inventor of the wonderful modes of wearing the hair which were in vogue for more than ten years: the coiffure à la dauphine, in which the hair was gathered up and rolled into curls which fell on to the neck; the coiffure à la monte au ciel, remarkable for its extreme height; the full-dress coiffure, called loge d’opera (1772), which made a ladies’ face seventy-two inches high from the chin to the top of the hair, which was divided into several zones, each one arranged in a different way, but invariably completed with three large feathers attached on the left temple, with a bow of rose coloured ribbon and a large ruby; the coiffure à la queasco (1774), in which the three feathers referred to above were placed at the back of the head; the pouf coiffure, which was a heterogeneous composition of feathers, jewellery, ribbons, and pins. Into this wonderful coiffure entered butterflies, birds, painted cupids, branches of trees, fruits, and even vegetables. In the month of April, the Duchesse de Chartres, daughter of the Duc de Penthièvre, appeared at the opera with her hair dressed in a sentimental pouf, upon which was represented her eldest son, the Duc de Beaujolais, in his nurse’s arms, a parrot pecking at a cherry, a little negro boy, and the initials worked in hair from the heads of the Ducs d’Orleans, de Chartres, and de Penthièvre. It was popularly said that Marie-Antoinette was Queen of the coiffure before becoming Queen of France, and her husband’s accession to the throne was hailed with delight by the hair-dressers and milliners.

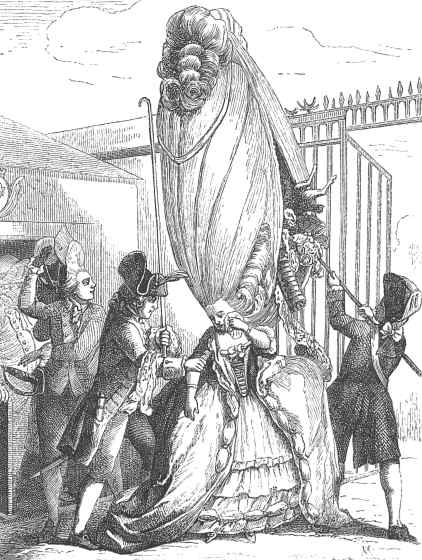

Soon afterwards appeared the head- dresses called au temps présent, which were caps trimmed with ears of corn, and crowned with two cornucopiæ. A colour called cheveux de la Reine was also invented, men and women’s hats aux délices du siècle d’Auguste, and a fresh attempt was made to revive the costume à la Henri IV. After Louis XVI. had come to the throne, Marie Antoinette exercised great influence, especially in everything connected with the fashions. Madame de Campan says in her “Memoirs” that the Queen had hitherto displayed great simplicity in her toilette, but her tastes became more expensive after her husband’s accession, and as she was copied by the ladies of the Court many of them exceeded their means so much that their husbands began to complain. The King disapproved this excessive luxury of dress, but he did nothing to check it. It may be said that the most insignificant events during his reign were seized upon as pretexts for bringing in some new fashions which, whenever they were patronized by the Queen, obtained universal vogue. She was very fond of plumes, and the mania for them was carried to such a point that their price increased ten-fold, and the choicest had been known to fetch as much as fifty louis. Soularie in his “Historical Memoirs of the Reign of Louis XVI.,” relates that “when the Queen passed along the gallery at Versailles, you could see nothing but a forest of feathers, rising a foot-and-a-half above the head, and nodding to and fro. The Princesses, aunts of Louis XVI., who could not make up their minds to adopt these new fashions and copy the Queen every day, called these feathers a horse-trapping.” As the height of the coiffures continued to increase, they at last reached such a pitch, says Madame de Campan, what with the strata of gauze, flowers, and feathers, that ladies found the roof of their carriage too low, and were either obliged to put their heads out of the window, or to ride in a kneeling posture. Nobody had so high a head-dress as the Queen.

It is impossible to describe in words these scaffoldings of hair, crimped, curled, frizzled, plaited, and surcharged with feathers, ribbons, gauze, wreaths, flowers, pearls, and diamonds. There were coiffures representing landscapes, English gardens, mountains, and forests, The fancy names given to them had rarely any analogy with their character or arrangement. The following are a few of the most eccentric of these names: the greques à boucles badines, the royal, the chien couchant, the hérisson, the hats à l’enigme, à la oiseau mont-désir, à la économie du siècle, au désir de plaire, the poufs à la Pierrot, the parterres galants, the caléches retrousées, the therèses à la Vénus pélerine, the caps au becquet, aux clochettes, and à la physionomie, the bonnets anonymes, the cornet-caps à la laitière, the baigneuses à la frivolité, coiffures à la candeur, au berceau d’amour, au mirliton, &c. When Marchand the lawyer, who was royal censor, published his book on head-dresses (1757), and, a few years afterwards his “Comédie des Panaches, as represented on the World’s stage, and especially in Paris” (1769), the head-dresses which he satirized were only worn by coquettes and eccentric ladies, but in the reign of Louis XVI., the most staid persons were carried away by the Queen’s example.

Satire, epigrams, and caricatures, secretly inspired by the King, were alike powerless against these extravagant head-dresses. For instance, there was a drawing which represented an architect-coiffeur who had constructed some scaffolding so as to be able to reach the top-storey of a head-dress, and another caricature advertised a portable ladder for hair-dressers to move around a lady’s head without disarranging the hair they were dressing. The police attempted to interfere in the matter, but all they could do was to prevent ladies from visiting a theatre if their head-dresses were large enough to obstruct the view. But, in spite of all this resistance, the principal feats of arms and politics were embodied in the head-dresses, and the successes of the French navy in 1778 gave rise to some twenty new modes of coiffure. One of them, invented after the naval combat in which La Belle-Poule had figured to great advantage (June 17th, 1778), consisted in the imitation of the frigate itself, with its masts, rigging and guns. All this will explain the infatuation of one hair-dresser who, in a pamphlet eulogizing his profession, wrote: “The coiffeur’s art is beyond question the most brilliant of all, inasmuch as it brings him in daily contact with the greatest, the most beautiful, and the most dignified people in the world.”

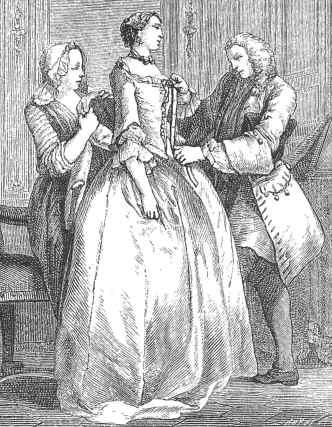

The toilette of a pretty woman was a sort of intimate reception, held in the sanctuary where the coiffure was elaborated. The goddess of the sanctuary received her small circle of intimates, dressed in a plain peignoir of embroidered muslin, and the hairdresser took an hour or more to complete his task.

During that time, the conversation went on without interruption, dealing with all the novelties of the day, though in the time of Louis XVI. it was considered good taste to give it a literary, scientific, and philosophical turn. The toilet-table was covered with all the new books, and those on serious subjects were latterly predominant. The gentleman of the house invariably sent to say that breakfast was served, and Madame’s reply generally was “not to wait for me.” The night toilet lasted almost as long as that in the morning, the only difference being that no company was admitted. Before retiring for the night, the lady’s-maid was consulted as to what should be worn on the following day.

We will not attempt to enumerate the fashions which succeeded each other so rapidly from 1781 to 1788, though the Queen, seeing the evils of this reckless luxury of toilette for which she was mainly responsible, endeavoured, but in vain, to moderate its excesses. The birth of the dauphin (October 22nd, 1781) was celebrated by the invention of head-dresses and costumes in commemoration of this auspicious event.

The Queen had already diminished the height of her head-dresses, wearing caps à la Henri IV., à la Gertrude, à la Colin-Maillard, etc. But all these were discarded for the coiffure à la Dauphin, and the coiffure aux relevailles de la Reine, who no longer controlled the changes of fashion which were guided by the caprices of the milliners and the hairdressers.There was a perpetual change in the materials used, but even these changes did not keep pace with the change of names which were invented rather to designate the colours and shades of the materials than to attract attention, such for instance as fleas’ bodies, fleas’ stomachs, Paris Mud, dandies intestines, suppressed sighs, indiscreet tears, etc. Henceforward, the Queen was not so much the originator of the fashions as she had been, though the famous Chanson de Marlborough was again brought into vogue because she had sung it (1782). The authors of the “Secret Memoirs” of Bachaumont say that “Since Marlborough’s ditty, everything new is à la Marlborough. Ribbons, head-dresses, waistcoats and hats, the latter particularly, are à la Marlborough.” When balloons were invented in 1783, everything was au ballon, à la Montgolfier, and so on. The success of “Le Mariage de Figaro” led to the invention of fashions named after personages in the piece: Chérubin, Suzanne, Basile, etc., and the popularity of the plays of Beaumarchais, Lemierre, Mercier and Monvel are attested by the fashions aux Amours de Bayard, à la Veuve du Malabar, à la Brouette die vinaigrier, à la Tarare, etc. The public newspapers published a description of some epicene animal said to have been found in Chili (1784), and all the previous fashions were eclipsed by the mode à la harpie (the name given to the animal in question ).

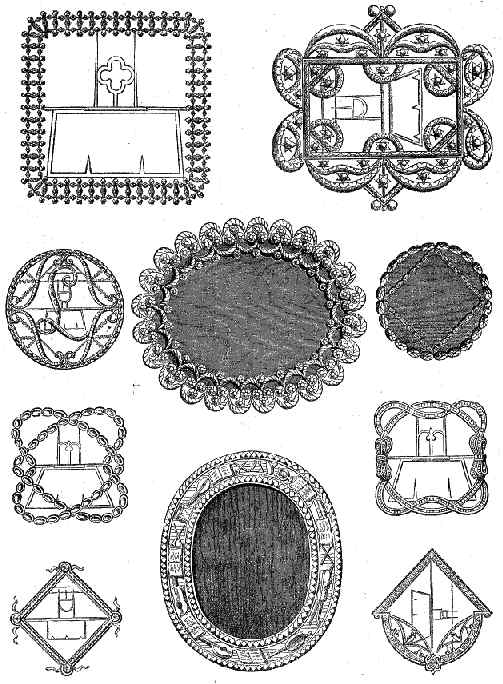

Men as well as women had been obliged to submit to the despotism of the tailor and the hairdressers. They wore their hair curled or plaited, in a pig-tail or rolled à la Panurge, and covered with pomade or powder. They still retained the small cocked-hat which they never wore but held under the arm or in the hand, and they adopted the use of hats, à la Hollandaise, à I’Anglo-Americaine, à la jockey, à I’Anglomane and à l’independant. Powder was used even by the cooks and footmen, and the republican, Sobry, in his treatise on “French Fashions,” asserts that powder in the hair is becoming as well as agreeable, and has been regarded as a prime necessity by all civilized peoples. Men’s costume was by no means in harmony with the gravity associated with a powdered head, for they wore a coat with the skirts running to a point and with an upright collar. This coat was either of wool or silk of some soft or showy colour, having, as a general rule, stripes of two colours, rose and blue, green and white, with a yellow or grey lining. Breeches made either of plush, rateen or rough cloth, a waistcoat of warped silk, and ribbed stockings completed the dress. A dandy looked more like a stage shepherd than anything else. Men were as fond of carrying gold-caskets, watches, rings, charms and buttons as the other sex were.The buttons used for the coat and waistcoat were of all shapes and of all materials; at one time in gold and silver with chased ornaments upon them; at another in mother of pearl and scented wood incrusted with precious stones; at another they consisted of gold and silver wrought into the shape of the wearer’s initials, and they were also ornamented with paintings under glass, insects, minerals, objects of natural history, and so on. Some of these buttons were two inches in diameter, and on them were painted comic riddles, the portraits of the twelve Caesars, the latest Kings of France, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, etc. The waistcoats upon which they were sewn were equally eccentric, hunting and military scenes, pastorals, and caricatures, being embroidered on them in silk of various colours. The dandies seemed to make themselves more conspicuous for their bad taste, in proportion as the ladies, under the influence of Marie-Antoinette, adopted simpler modes of dress. Mercier (1786) declared that “nothing can be more elegant and tasty than the present mode of female costume,” but he could not have said this of male attire. Though Louis XVI. was very plain and even careless about dress, he was not copied even by the bourgeoisie, and when he visited the HôteI Dieu in 1786 ‘(February 27), people were astonished and even pained at his unkingly appearance. Restif de la Bretonne says: “This fat man, as they called him, had a badly combed round wig, and wore a seedy frock-coat.”

The reform of the fashions, if not of all sumptuary profusion, began both at Court and amongst the public in 1783. Madame de Sartory wrote at that period (perhaps deceiving herself as to the progress of this reform which was very slow): “Luxury is no longer displayed in buildings and external decorations. The carriages are plain, while the servants are less numerous, the fine clothes out of fashion, expensive horses are no longer kept, diamonds are at a discount, and jewellery has fallen into discredit.” The time had arrived when the Queen, disgusted with politics, withdrew from the Court, and sought distraction in the rustic amusements of the PetitTrianon, where she showed herself in the costume of an Alpine shepherdess to the ladies of her suite and the members of the royal family, though the dressmakers betrayed her secret to the whole world. Madame de Sartory, author of the “Petit Tableau de Paris,” quoted above, says: “Women’s dress was never so plain as it is now. You see no dresses surcharged with trimmings, or sleeves with three rows of lace. A straw-hat with a knot of ribbon, a plain neckerchief, and an apron for house wear have taken the place of curls, and frizzles, and falbalas. The men are dressed still more simply, and have discarded their embroidered coats, and scarves, and epaulettes.”

The Court dress, with the panniers, the lappets, and the high headdresses were still worn on state occasions, but outside the Court everything English and American was brought into vogue. Straw hats attached with a piece of ribbon, short dresses of some light material, large aprons, enormous fichus, and shoes without high-heels were all the rage. Many women belonging to the upper bourgeoisie, and some of those appertaining to the highest classes of society, laid themselves out to be, or to appear to be very serious, and they assumed the air, and even, to a certain extent, the costume of the other sex. Mercier, writing in 1788, said: “Women actually go about in male attire; a frock-coat with three collars, the hair tied à la catogan, a switch-stick in their hands, shoes with low heels, two watches, and an open waistcoat.” The men, as if to outdo these austere and incongruous fashions, had taken to the black frock, left off powder, and again wore the cocked-hat, They vied with one another in their imitations of the English and Americans, and the ladies went mad over hats à I’Anglaise, and à la Jockey, dresses made of English poplins, moiré, tulle, and lawn. Steel and glassware had taken the place of diamonds, and French fashion, so rich and so magnificent, so capricious and so varied, so elegant and so gracious, had almost disappeared at the dawn of the Revolution. It was a kingdom whose subjects had withdrawn from it their allegiance