Contents

Contents

The Province of Georgia had a more diverse economy than many of the other Southern Colonies, but was still heavily reliant on cash crops and plantation-based farming, especially from the 1750s onward.

Agriculture

During its early history, Georgia’s agricultural trade primarily involved small-scale subsistence farming.

The colony’s first settlers generally farmed their own land, planting crops such as wheat and corn, and occasionally raising animals, in order to support themselves.

However, this changed in the 1740s and 1750s as Georgia became more developed, especially after the colony’s ban on slavery was lifted in 1751.

With its warm climate, fertile soils, and long growing season, large numbers of agricultural plantations began to appear in Georgia. These large-scale farms were normally established in the coastal lowlands, which had the best soil for farming.

Plantation owners focused on growing cash crops – agricultural output designed to be sold, rather than consumed domestically.

In Georgia’s case, the biggest cash crop was rice, but indigo (used to create dye) was grown as well, plus smaller quantities of tobacco and silk. These raw outputs were often processed locally on the plantations, for example, milling rice into a final product ready for cooking, or fermenting indigo into a semi-finished product.

Once ready for export, these products were primarily sent to Europe through Great Britain, or to other British colonies in the Caribbean or America.

Further inland, settlers continued to grow crops and raise livestock, but these areas were generally poorer, and focused more on supplying provisions (for example, horses and oxen, which were used for transport) to the plantations.

Slave labor

Georgia’s cash crop plantations relied on slave labor.

Slavery was officially banned in Georgia in 1735, but as the plantation economy grew, demands for labor increased, and some landowners began to illegally keep slaves.

Facing pressure from settlers and with the colony struggling economically, Georgia lifted its ban on slavery in 1751, and the practice remained legal after the colony came under royal control in 1752.

As a result, from the 1750s onwards, large numbers of African slaves were brought into Georgia. By 1780, estimates recorded 20,831 people as Black in the colony – nearly half of the entire population.

The vast majority of these slaves worked on plantations, for example harvesting and caring for crops, sowing seeds, maintaining buildings, and fixing tools. Some slaves also worked in households and at ports such as Savannah, doing jobs such as cooking and cleaning, repairing ships, and unloading cargo.

Fur trade

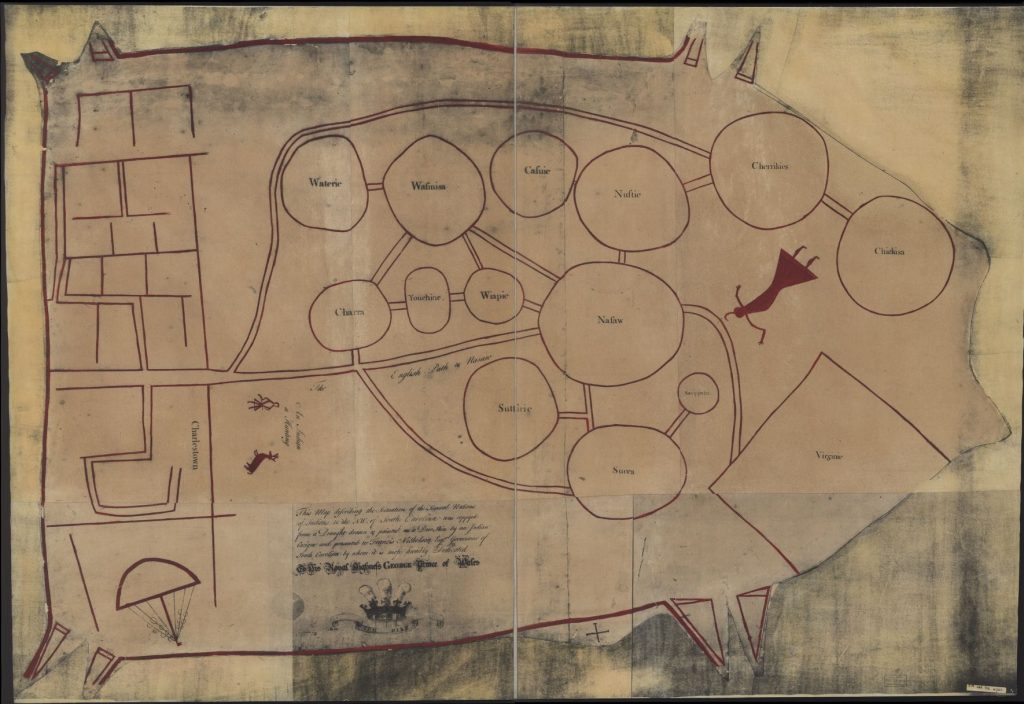

Georgia had a substantial fur trade, centered around the colony’s interior.

Deerskins and other pelts were purchased from Native American hunters, before being used to make leather products, or exported to Europe for use in high fashion.

Often, instead of cash, indigenous tribes were given tools, clothing, weapons, or foodstuffs in exchange for the furs they provided.

However, the industry was heavily influenced by the state of relations with native tribes. At times, alliances were formed and trade boomed, and at others, conflicts occurred with local tribes or along trade routes, resulting in a reduction in fur trading.

Lumber and forestry products

Georgia had millions of acres of pristine forests when it was first settled, giving rise to a significant lumber industry.

Trees were cut down to make houses, barns, barrels, and ships, though Georgia itself did not have a major shipbuilding industry.

Pine trees were also used to create goods known as naval stores – products used to make ships seaworthy.

This was a particularly profitable industry in Georgia due to the number of pine trees in the colony, especially along the coast.

Pine wood was used to create:

- Tar: a dark, sticky liquid made from burning branches/logs, used to protect ships’ decks, hulls, and ropes from the elements.

- Pitch: a more solid version of tar used for waterproofing (such as caulking gaps).

- Turpentine: a solvent made from pine sap used in paint and varnish, also used on ships for weather protection.

Imports

As a plantation-based economy, Georgia was extensively focused on producing cash crops to economically sustain itself.

As a result, the colony had little in the way of domestic manufacturing capabilities during the colonial era.

Therefore, it needed to import large quantities of certain goods from other colonies or internationally, including:

- Tools and machinery.

- Iron products such as horseshoes, buckles, and nails.

- Textiles such as clothes, including shoes.

- Oil and paint.

- Weapons and gunpowder.

- Foodstuffs such as flour and meat (especially from the Middle Colonies).

- Alcohol such as rum.

However, under trustee control, hard alcohol was prohibited in Georgia in 1735 and could not be imported, in order to discourage unruly behavior. This ban was lifted in 1742.

Most of Georgia’s imports came from Great Britain, though some products, such as rum, were a specialty of Britain’s other overseas territories in the Caribbean.

Ports and exports

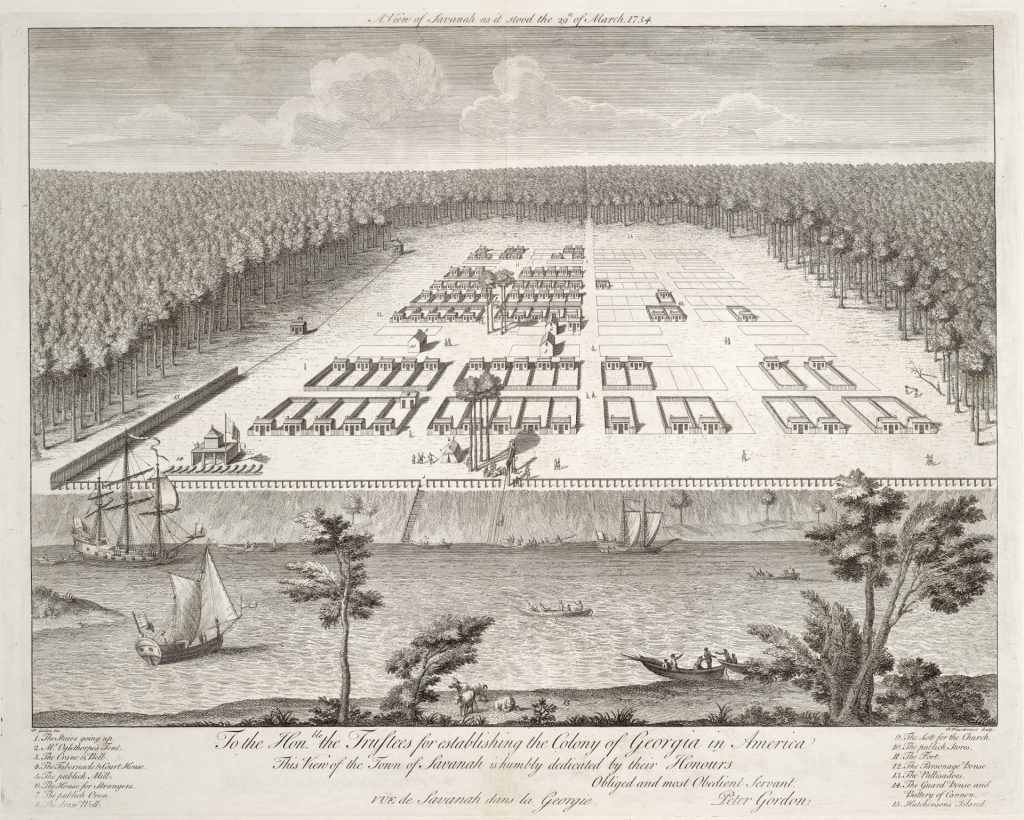

Much of Georgia’s exports moved through the Port of Savannah, which was the largest trade hub in the colony. However, exports also flowed through Sunbury and Darien, which acted as smaller, supplemental trade centers.

Crops would be shipped from nearby coastal plantations to the ports via the ocean or inland rivers, before being forwarded on to Europe, the Caribbean, or elsewhere in the Thirteen Colonies. Meanwhile, ships would arrive with crucial imports such as tools and textiles.

Major ports such as Savannah supported a sizable localized shipyard and maritime industry. Though the majority of ships were built in New England and the Middle Colonies, Georgia’s ports helped maintain them, and there was a large supporting industry around cargo, transport, and even services such as maritime insurance.

Economic subsidies

Of the Thirteen Colonies, Georgia was the one that most relied on government support for its economic survival, especially in its early history.

The colony first received a grant of £10,000 from the British government in 1733, which is about $2.8m in today’s money. Funding continued throughout the colonial era, with smaller amounts provided by the government from the 1750s onward.

The purpose of this investment was to establish Georgia as a buffer state between its other twelve American colonies and Spanish Florida, which posed the threat of invasion. The British Crown was willing to spend large sums of money in order to maintain this buffer state.

However, though Georgia eventually became more self-sufficient over time, it did not become as profitable as its other neighbors in the south, such as South Carolina.