Contents

Contents

Jacobites were people in the United Kingdom who supported the return of King James II to the British throne, restoring the House of Stuart to power. James is written as Jacobus in Latin, giving rise to the name Jacobites.

After the Glorious Revolution in 1688, James II fled to France, and the British parliament appointed Mary II and William of Orange as joint monarchs of the country.

The Jacobites argued that monarchs could only rule with divine authority from God, and that the parliament’s decision to appoint a Protestant monarchy was illegitimate. Many Jacobites were Catholics, and in Scotland, many were loyal to the Stuart dynasty, which had ruled the country for decades.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Jacobite movement had a presence in England and Ireland, and had strong support in the Scottish Highlands.

On 19 August 1745, James II’s grandson, Charles, started a Jacobite uprising in the Highlands, capturing Edinburgh and heading south, expecting significant support from English Jacobites. Despite reaching as far south as Manchester, the support never materialized, and the Jacobites were driven back into Scotland.

Post-rising Jacobite immigration to America

After the Jacobite Rising of 1745, the Jacobites faced significant persecution from the British, who feared another rebellion. Many were arrested for treason, and more than 100 Jacobites were executed. As a result, some fled to the Thirteen Colonies in the late 1740s, with Jacobite immigrants settling in New York, as well as North Carolina.

At the time, the Thirteen Colonies were majority Protestant, and as a result, most Jacobites kept their political beliefs to themselves. However, they still played a part in colonial culture, by engaging with political and legal issues, spreading Scottish culture, and participating in the military.

It’s important to note, large-scale Jacobite immigration to America began much earlier than 1745. There was another failed Jacobite rising in 1715, which caused many to leave for America. As of the mid-1750s, it was likely that there were at least 20,000 Scottish immigrants in the Thirteen Colonies.

The Seven Years’ War

Post-1745, there was a period of assimilation of Scottish and English society.

After the Jacobite Rising, the British tried to destroy Highlander and Scottish clan culture, such as through the Heritable Jurisdiction Act of 1746, which diminished clan chiefs’ power.

They also established military bases (forts) in Scotland, providing employment opportunities for the Highlanders, leading to further integration of the British and Scottish.

By the time the Seven Years’ War started in 1756, a significant portion of the British Army was made up of Highlander units.

These soldiers fought alongside the English in America against the French, and after the war ended in 1763, many Scottish veterans stayed in America. They were offered land grants by King George under the Royal Proclamation of 1763, allowing them to settle long-term in a number of the Thirteen Colonies.

The American Revolution

Given that the Jacobites had attempted to overthrow the British monarchy, you might expect them to have supported the Patriot cause in America.

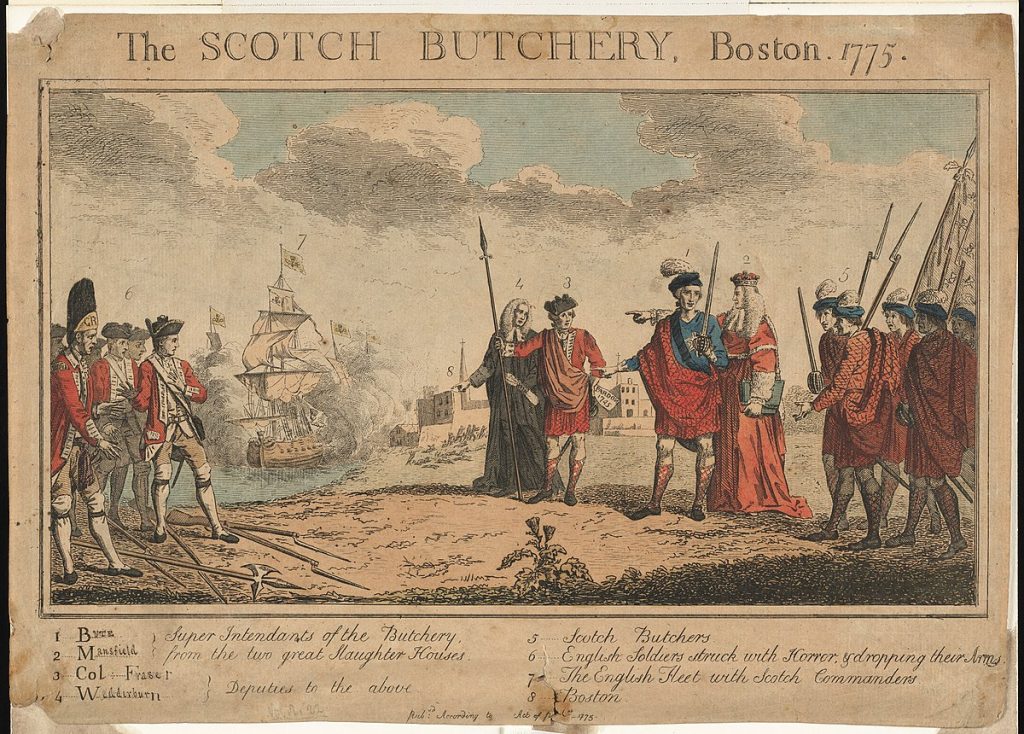

However, the majority of American Jacobites were Loyalists, and the same can be said for the broader Scottish population in America at the time as well.

Most Scots were new to the colonies, and wanted a stable system of government, based on biblical ideals. Above all, Jacobites were Monarchists – they believed in the King’s divine right to rule. The idea of a republic was not compatible with Jacobitism.

The Jacobites wanted America to remain loyal to the crown, and to see a return to the House of Stuart, rather than a transition to an independent republic.

Also, King George III was considered a friend of the Catholics, and sympathetic to the Jacobites. He was not as hard-line as many of the other Protestant leaders that preceded him – he repealed the Dress Act of 1746 for example, allowing Highlanders to wear kilts and other traditional garments once again.

As a result, most Scottish soldiers in America fought on the side of the British, such as Allan Maclean, who participated in the Jacobite Rising of 1745. He went on to become a British Army general, who fought in the French and Indian War, before leading the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) against the Continental Army at the Battle of Quebec in 1775.

However, there are also notable examples of Scots who fought for the Patriot cause, such as John Paul Jones.

Hugh Mercer was another Jacobite who participated in the 1745 rebellion, before becoming a Continental Army general. He was later killed in action at the Battle of Princeton.

Scottish military units

The Scottish were regarded as fierce, disciplined fighters during the American Revolution, and they played a significant role in the conflict.

Apart from the 84th Regiment of Foot’s role in defending Canada, the 71st Regiment of Foot (Fraser’s Highlanders) fought for the British in the south, and the 42nd Regiment of Foot (Black Watch) played a role at the Battle of Fort Ticonderoga and the Battle of Long Island.

On the American side, Scottish immigrants played a role in certain local militias, and made up a significant proportion of the Pennsylvania Line, who fought at the Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton.