Contents

Contents

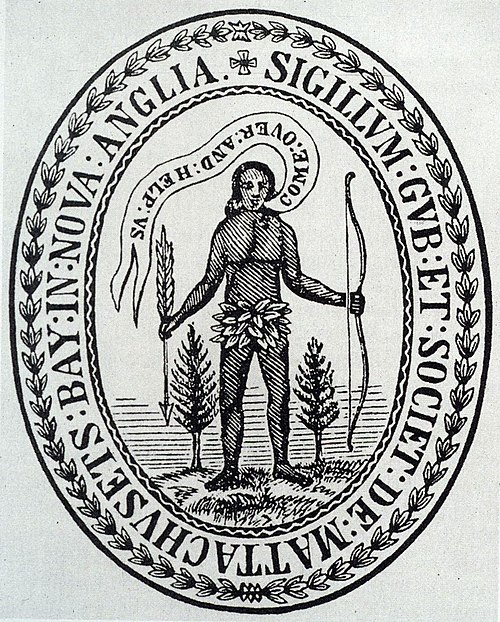

Massachusetts Bay was a Puritan theocracy, with religion affecting many aspects of the colonists’ lives and society.

Founding

Massachusetts was settled by English Congregational Puritans in 1628.

Puritanism was a form of Protestant Christianity that aimed to purify the Church of England, by removing what they saw as elements of Roman Catholic practices.

They wanted to implement strict discipline and conformance to Christian moral codes across all aspects of society, including government, education, and the justice system. Massachusetts would be their “city upon a hill” – a model Puritan society away from the more progressive types of Protestantism that dominated England at the time.

Congregationalism is a type of church governance system that most of the colony’s early settlers practiced, whereby local churches were largely autonomous, rather than being overseen by a central figure such as a bishop or higher minister.

1630s to 1660s: establishing Puritan society

As the Massachusetts Bay Colony began to establish itself in the early 1630s, Puritan churches were soon established as towns were settled, beginning with Salem and Boston.

Residents were required to pay taxes to the local ministry, regardless of their religious denomination. Congregational Puritanism was the official religion of the colony.

Anglicans and other Protestant denominations were specifically discriminated against. Voting rights were restricted to male members of the approved church until 1664, and initially, Quakers were specifically forbidden from the colony by law.

Church membership was also hard to attain as it required baptism and proof of having undergone a conversion experience – a moment of profound religious discovery – in which an individual discovers God and the power of Christianity in their life, and formally converts to Puritanism.

Mary Dyer, a Quaker missionary and former Puritan, was hanged in Boston Common in 1660 for entering the colony as a member of a disallowed religion. The British put an end to Massachusetts’ practice of whipping, beating, and executing Quakers with two decrees enacted in 1661 to 1665, though they were still legally persecuted by local magistrates on a regular basis.

Education was prioritized to ensure that the population could read the Bible, and strict adherence to Puritan values was required. Harvard College was founded in Cambridge in 1636 specifically to train church ministers.

The Puritans were heavy believers in spiritual and divine forces, and often sought to understand God’s will through things they experienced on a day-to-day basis. As a result, droughts, epidemics, and weak/strong harvests were marked with public fasts or thanksgivings, meaning that Puritan principles severely affected everyday life.

Dissenters were not tolerated, and were often banished from the state when they were seen to question Puritan values. For example, Roger Williams was exiled in 1635 when he argued for greater separation of church and state, leading him to establish Rhode Island as a safe haven for others trying to escape Massachusetts’ strict religious law.

In 1662, church membership began to fall as second-generation migrants struggled to fulfil the requirements to join.

The church therefore implemented the Half-Way Covenant, which allowed the children of those who were baptized but not converted to undergo baptism and become partial members of the church.

This move was controversial, but succeeded in boosting membership numbers.

1670s to 1690s: Puritan hysteria and the Salem Witch Trials

In the late 1600s, Massachusetts came under increasing threat from Native American raids and border conflicts with nearby colonies.

Social tension and fear also increased due to poor harvests and smallpox epidemics.

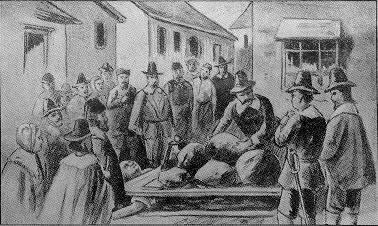

In 1692, two young girls in Salem came down with an unknown illness. When the cause of their condition could not be assessed, and others presented with similar symptoms, three women in the village were accused of witchcraft.

The witch hunt continued, and by May 1693, 19 people had been hanged, and another died by torture after refusing to enter a plea.

Soon, doubts arose around the evidence presented in the trials, and the possibility that some of the witchcraft accusations were fueled by family feuds.

Victims’ relatives immediately petitioned to overturn the convictions, and the Massachusetts government began to slowly repeal them over the next 20-30 years.

1700s to 1770s: gradual softening of Puritan devotion

Beginning in the 1700s, exemptions to parish tax laws were opened for a very limited number of other Protestant denominations.

Anglicans could redirect their taxes to their own ministry, rather than being forced to support the Congregational Puritan church. It would take until the mid-1700s for this freedom to be opened to Quakers.

In the 1730s and 1740s, evangelical preachers such as Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield toured Massachusetts, delivering powerful, emotional sermons, promoting increased spiritual intensity and Christian devotion.

In Christianity, this period of religious revival is known as the first “Great Awakening,” and led to a split between “Old Light” followers who preferred the traditional ways of worshipping, and “New Light” believers who bought into the progressive, evangelical ways of Whitefield and other preachers.

In Massachusetts, this led to a fragmentation of the relatively concentrated Congregational church. Public religious debate became normalized, and tax diversion programs for dissenters were expanded.

The Great Awakening also pushed many believers away from Puritanism towards the Baptist faith, which led to another small decrease in the Congregational Church’s influence.

From 1750 until the American Revolution, Puritan influence continued to decline at a slow pace, but Massachusetts continued to be dominated by Puritan values and the Congregational Church throughout its colonial history. Only in 1833 was Congregationalism removed as the official church of Massachusetts.