Contents

Contents

The Middle Colonies were religiously pluralistic, home to a diverse range of different religions, including Quakers, Presbyterians, Lutherans, and Mennonites, as well as a small minority of Jews and Catholics.

Early history

When New England was first settled, many of its early colonies, especially Massachusetts, were designed as Puritan model societies. As a result, there was very little separation of church and state, and almost complete intolerance for other religious sects.

By contrast, the Middle Colonies were extremely diverse, and had much greater levels of religious tolerance.

Having been originally settled by the Dutch under the name New Netherland, New York was home to a large number of members of the Dutch Reformed Church when it was captured by the English in 1664.

When they took control, the English put laws in place to organize settlements into parishes. Towns were encouraged to have a Protestant church, and the Ministry Act of 1693 introduced taxes to fund these institutions.

Later on, as more English migrants moved to the region, New York became even more diverse. The Anglican Church grew, and Scots-Irish Presbyterians also moved to the colony.

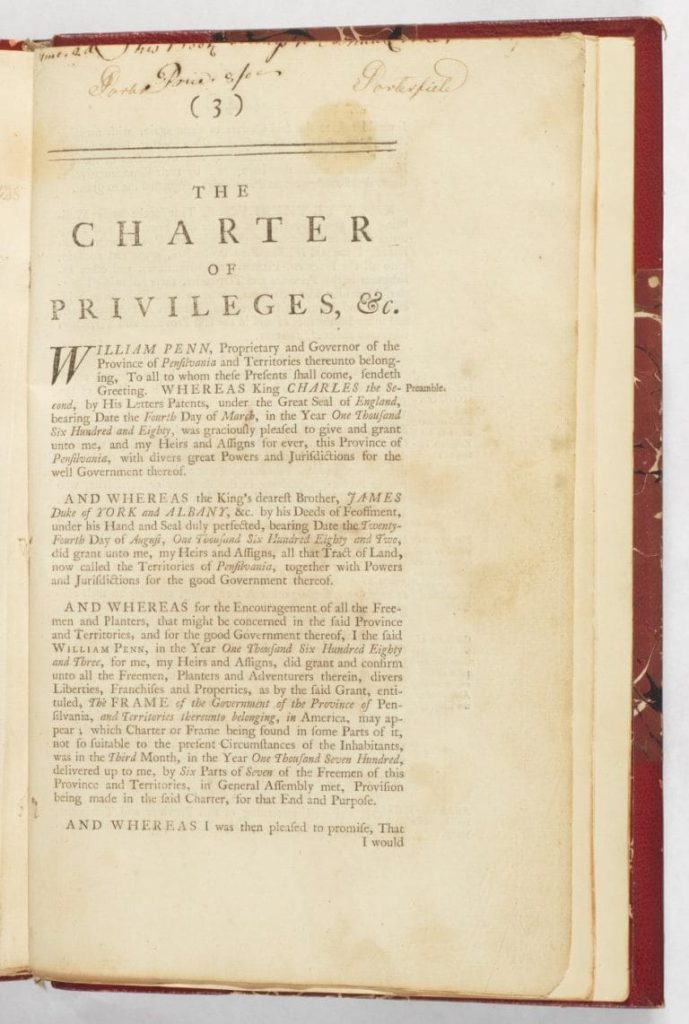

Pennsylvania was founded on Quaker principles of “liberty of conscience,” meaning that all monotheistic religions (that recognized one God) were permitted to worship freely.

Around the turn of the 1700s, this attracted large numbers of different religious groups to the colony, including Scots-Irish, Anabaptist/Pietist groups, and Lutheran and Reformed communities, especially from Germany.

Delaware was similar to Pennsylvania, as it was effectively part of the larger colony until 1704, and continued to be influenced by the same principles after gaining independence.

It was a tolerant colony with a large Quaker population during its early history, though the area also began to attract significant numbers of Anglicans, Mennonites, and eventually Methodists over time.

Delaware was also formerly under Dutch and Swedish control, meaning there were large numbers of Lutherans and Dutch Reformed Church members in the colony.

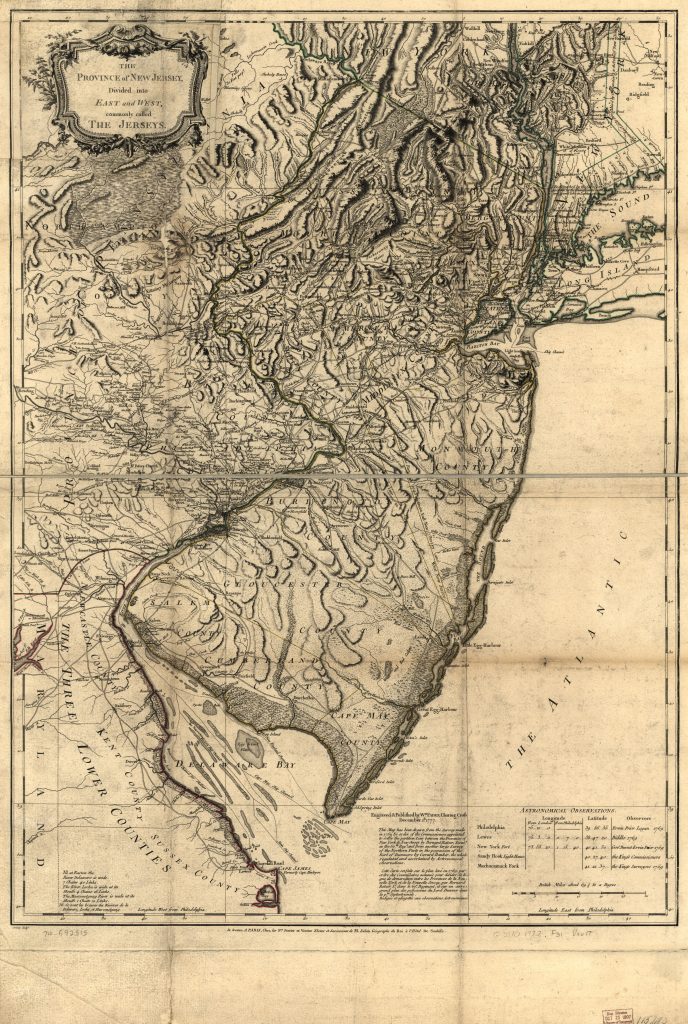

Like Delaware, New Jersey was heavily pluralistic, with Quakers, Dutch Reformed, Lutherans, and Presbyterians settling in large numbers in different parts of the colony. Quakers predominantly settled in the west, while the east of the colony was more diverse.

Anglicanism gained influence in New Jersey over time, but the colony never had an official religion.

There were also Jewish minorities in the Middle Colonies, especially in New York, where the first Jewish settlers arrived during the period of Dutch control. However, they were relatively small in number compared to the Protestant majority.

Catholics also featured in the Middle Colonies during its early history, predominantly in Pennsylvania. Like the Jewish populations, they were also limited in number.

Religious restrictions

Despite the religious tolerance of the Middle Colonies, people of certain faiths were still discriminated against.

With few exceptions, Protestants of all denominations were allowed to worship freely and run for government office in the Middle Colonies. This was different from some areas of New England, such as Massachusetts, where Quakers, Mennonites, and other non-Puritan Protestant denominations were discriminated against and prevented from participating in politics.

Though Anglicanism grew over time, mandatory parish taxes were generally rare to see in the Middle Colonies, meaning that other religious sects were not normally forced to fund the Church of England.

However, the Middle Colonies all required elected representatives to swear their belief in and allegiance to Jesus Christ, which prevented Jewish people from running for office.

With these restrictions in place, Catholics could technically join the legislative assembly at times, but in reality, they were distrusted by the Protestant majority, and were often excluded from society and prevented from worshipping freely, especially in New York.

Catholics were most tolerated in Pennsylvania, which allowed for liberty of conscience, and the Quaker majority was welcoming of non-Protestant monotheistic religions.

Religious conflict

Due to the diversity of the Middle Colonies, there were occasional disagreements and conflicts between different religious sects.

In New York, which was the most Anglican of the Middle Colonies, there were attempts to implement church taxes in the 1690s. These efforts were resisted by Protestant dissenters, including Quakers.

New York also moved against Catholicism specifically around 1700, in response to growing tensions between Protestants and Catholics in Europe. This led to Catholics being banned from voting, and their priests were threatened with life imprisonment if they were to perform their religious duties.

In the mid-1700s, frontier defence was becoming a real issue for Pennsylvania, especially during the French and Indian War.

Quakers and Moravians opposed the militarization of the colony, and as pacifists, refused to fight against the Native American tribes. As a result, a large number of Quakers resigned from the Pennsylvania government in 1756.

Hostility towards pacifist sects also helped fuel the Paxton Boys crisis from 1763 to 1764, when a Scots-Irish militia massacred the Conestoga tribe and then marched towards Philadelphia, targeting indigenous peoples sheltered by the Quakers and Moravians as they went.

Many members of these sects spent significant effort on missionary work with Native American tribes in the early to mid-1700s, which also led to conflict with Presbyterian groups that viewed the indigenous population as a threat to the colony.

The First Great Awakening

In the first half of the 1700s, religion changed significantly and became even more diverse in the Middle Colonies, as the First Great Awakening swept across British North America.

During this period, evangelical preachers traveled across the Thirteen Colonies, challenging the long-established, rigid ways that Christianity was practiced at the time.

They emphasized a more individualistic, open approach to religion, with energetic, fast-paced sermons, and encouraged religious participation among poor and marginalized groups.

This movement was designed to re-engage the public with religion, and it was very successful in the Middle Colonies.

In New Jersey, the preachings of Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen fundamentally changed the Dutch Reformed Church, re-energizing church services, and successfully engaging younger worshippers in the mid-1720s.

Beginning in 1739, George Whitefield, a famous preacher from England, traveled throughout Delaware and Pennsylvania, and thousands of people turned out to hear his speeches.

In Philadelphia, he preached from the old courthouse on Market Street at 2nd Street (in today’s Old City area). It is said that “his voice was distinctly heard on the Jersey shore, and so distinct was his speech that every word was understood on board of a shallop (a small boat) at Market Street wharf, a distance of upwards of four hundred feet from the court house.”

In the Middle Colonies, the Great Awakening split many branches of the Presbyterian movement into separate traditional and evangelical factions, called the Old Side and New Side respectively.

While many Presbyterians bought into the evangelical style of worship, especially younger and poorer groups, many others continued to practice the more modest, more traditional form of their religion.

Towards Revolution

From the 1750s onwards, the Church of England and traditional Presbyterian institutions continued to gradually lose influence, as Middle Colony society continued to move away from the established churches.

Freedom of religion and diversity in belief continued to increase as the populations of the colonies rose. This accelerated as greater numbers of slaves were imported into New York and New Jersey in particular, bringing with them their own spiritual practices from their homeland.

There were limited missionary efforts to convert slaves to Protestantism, but many African Americans who did convert blended their homelands’ methods of worship with elements of Christianity.

In the second half of the 1700s, Jewish and Catholic populations in the Middle Colonies remained relatively low, though they were growing. The first synagogue was built in New York in 1730, and the first Catholic church in the Middle Colonies was established in Philadelphia in 1733, followed by a second one in Bally (PA) in 1741.

By the 1770s, religious worship placed a significantly greater emphasis on individualism and the equality of all men in the eyes of God compared to a century earlier, in large part thanks to the Great Awakening.

This played a small but significant role in the eventual lead up to the American Revolution, causing the colonists to resist the divine authority of the British Crown when faced with unfair taxation without representation.

To learn more about religion in the Middle Colonies, read our dedicated articles on this subject for New York Colony, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.