Contents

Contents

The Province of New Hampshire was initially settled mostly by Puritans, but was more accepting of other denominations compared to colonies like Massachusetts, and gradually became more religiously diverse as the 1700s progressed.

Founding

New Hampshire was initially settled in 1623, beginning at Hilton’s Point (now Dover) and Odiorne’s Point (now Rye).

At the time, many of America’s early settlers were Puritans – a type of Protestantism that requires strict adherence to Christian moral codes.

Established in 1630, Massachusetts was governed under Puritan principles, with laws drafted based on religious scripture, and little separation between church and state.

As a result, in the 1630s and 1640s, some moderates moved to New Hampshire, leaving Massachusetts in order to escape the colony’s theocratic governance system, as well as for economic opportunity, seeking farmland and lakes for fishing.

However, the majority of those who migrated were still Puritans, and the initial religious makeup of New Hampshire reflected this.

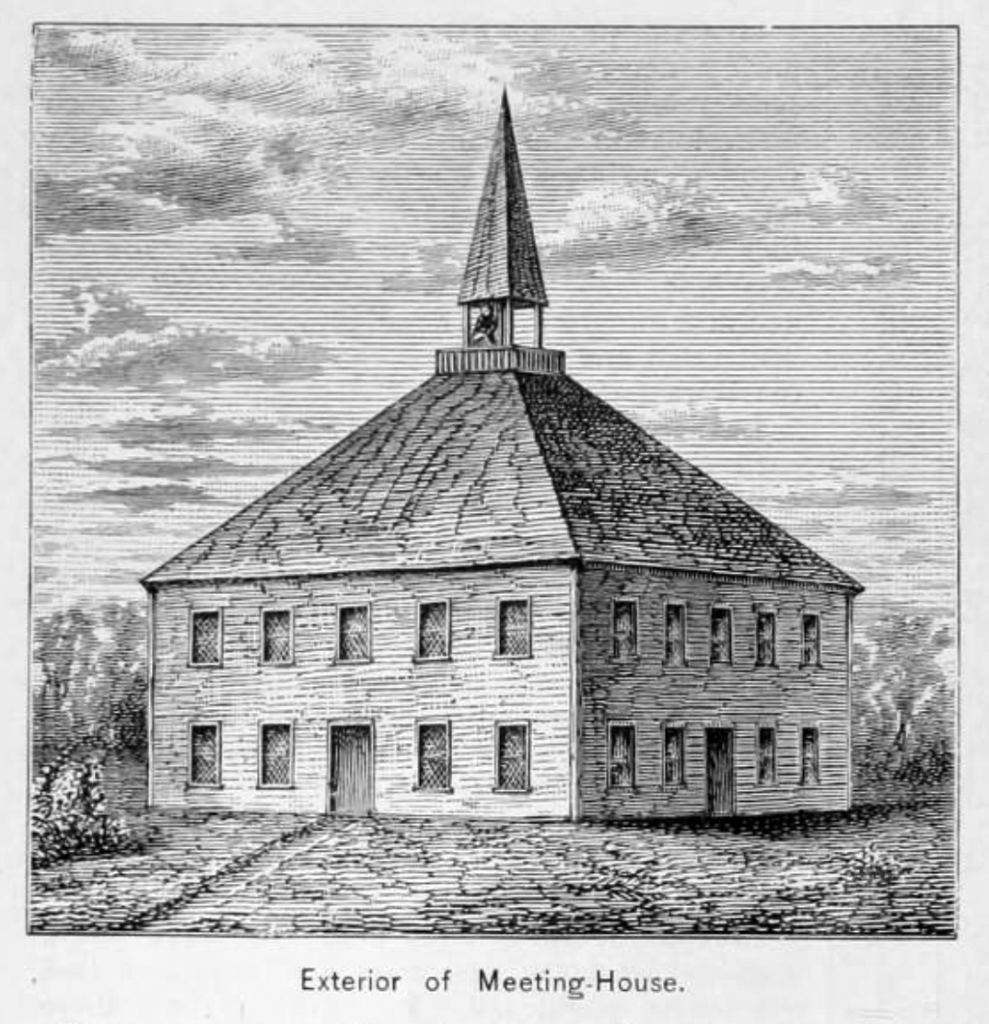

Early town life was centered around the Congregational church and its meetinghouse, with compulsory parish rates – taxes that had to be paid to the ministry, no matter the resident’s religious denomination.

Religious dissenters (who did not support the local church) were eventually allowed to apply for parish tax exemptions in some areas, as long as they still practiced the Protestant faith, and instead paid tax to their own minister.

Due to religious conflict in England and Europe at the time, Protestants and Catholics did not get along. It was thought that Catholics were potential enemies of the state because their loyalties lay with a foreign power – the Pope – rather than with the English Crown.

To participate in society (vote) or run for office, New Hampshire residents were required to swear their allegiance to the English monarch, meaning that Catholics were effectively excluded from the province during the colonial era, similar to in most of the other Thirteen Colonies.

Catholics were not eligible for dissenter tax exemptions, nor were Jews or other non-Protestants.

Religious diversity increases

As New Hampshire grew, so did its diversity, and the range of practiced religions in the province.

From 1714, New Hampshire law allowed towns to select their own church minister of any Protestant denomination. There was no single colony-wide official church, though the province was still dominated by Congregationalism.

This meant that certain settlements dominated by other sects could pay taxes to their own church, rather than being forced to fund a different denomination, as was the case in Massachusetts.

In the late 1710s, New Hampshire’s majority-English early settlers were joined by large numbers of Scottish and Irish, who were predominantly Presbyterian, and created settlements named after cities in their home countries, such as Londonderry.

Around the same time, the Presbyterians were joined by Baptists and Methodists, as well as Quakers. Anglicans were centered around Portsmouth, and organized the first Church of England parishes in New Hampshire.

The Great Awakening

From the 1730s to 1750s, American Christianity underwent its first “Great Awakening” – a period of increased religious interest and intensity, commonly known as a revival. This period of revival was especially strong in New Hampshire.

An evangelical priest named George Whitefield toured New England, giving emotional speeches to huge crowds who lined up to provide conversion testimonies – sharing how religious conviction helped them overcome problems or changed their life.

Many churches in New Hampshire embraced revivalism, as local ministers copied the new, exciting style of sermon. Baptists and Presbyterians were particularly energized by the awakening, sometimes forming new congregations based on revival styles of worship.

However, there were many who preferred the old, calmer, more traditional way of worshipping and conducting sermons. Certain groups separated to perform sermons their own way, forming “New Light” (progressive, evangelical) and “Old Light” (conservative, traditional) sects.

Due to the religious split that occurred, conflict arose over parish tax rates in New Hampshire.

When ministers embraced revivalism, more conservative residents no longer wanted to financially support their congregation. The reverse was also true when residents were overcome with revival energy, but their ministers did not adapt their sermons accordingly.

Though it caused conflict, the Great Awakening also increased religious diversity in New Hampshire, in that it led to the formation of a much broader range of different Protestant sects that were practicing in the colony.