Contents

Contents

The Colony of New Jersey had a diverse economy, predominantly focused on agriculture and maritime trade, and with a number of smaller manufacturing and natural resources industries taking off in the mid-1700s.

Agriculture

New Jersey was known as one of the “breadbasket” colonies in British North America.

The region had fertile soils and a relatively warm climate compared to New England, leading to a longer growing season.

Many settlers lived on farms, especially in the western half of the colony, growing crops such as wheat, maize, and barley, and also raising livestock such as cows, pigs, and sheep.

Much of New Jersey’s agricultural output was exported elsewhere in the Thirteen Colonies and internationally, especially to Britain, and especially from the mid-1700s onward.

The colony had a network of gristmills powered by rivers, allowing it to export products such as flour as well as raw grains to other trading partners.

The majority of farms were owned by independent landowners, who worked on their own fields, sometimes employing laborers to help with growing and harvesting. There were few large manor-style farms owned by a single proprietor, unlike in nearby colonies such as New York.

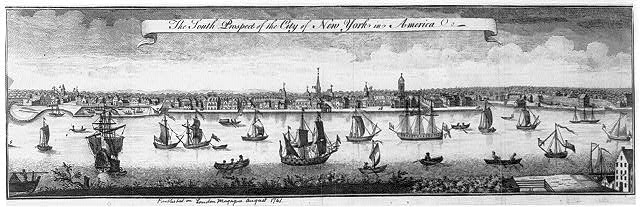

Ports and naval trade

New Jersey did not have major ports of its own in the colonial period.

However, as Benjamin Franklin described, the colony was “tapped at both ends,” meaning it was in close proximity to New York and Philadelphia in the northeast and southwest – two of the most active Atlantic ports in the Thirteen Colonies.

As a result, most of New Jersey’s agricultural exports flowed through these ports, rather than being sold in or shipped from the colony itself.

Despite this, the New Jersey ports of Burlington and Perth Amboy were home to a small but significant shipbuilding and maritime industry, beginning around the turn of the 18th century.

Mining and minerals

In South Jersey, bog iron was mined around the Pine Barrens area, beginning in the 1730s.

Clumps of the raw material, known as bog ore, were extracted from swamp bottoms before being washed, dried, and smelted in furnaces to create an intermediate material known as pig iron.

The Pine Barrens were the perfect place for this industry due to the huge areas of forests available in close proximity to swampy, low-lying marshlands. Trees were cut down to make charcoal, which fuelled the blast furnaces used for smelting.

Mining, refining, and smelting operations would usually occur at the same facility, before pig iron was transported to a manufacturing center, or exported to a different colony.

Also, in the north of the colony, hard-rock iron was mined using more traditional methods, such as at the Ringwood Manor Iron Complex in Passaic County, beginning in the 1740s.

This involved tunneling underground to extract iron ore, before the rock was crushed, processed, and smelted to produce a better quality (but harder to extract) grade of pig iron compared to what was produced from bog ore in the south.

Pig iron was used to create items such as nails, barrel hoops, horseshoes, and eventually munitions for the Revolutionary War.

Lumber

Apart from supplying wood used to make charcoal, South Jersey’s forests also supported a much broader lumber industry.

Around the Pinelands, trees were chopped down to harvest timber used to build houses and ships, produce barrels, and create a range of other products.

Water-powered sawmills were set up along rivers and streams to process lumber into sheets of timber that could be used in final production.

Glassmaking

New Jersey is considered the birthplace of glassmaking in America.

The industry began in the colony with the Wistarburg Glass Works, founded in 1739 in Salem County. It relied on local supplies of sand as a raw material, as well as wood from nearby forests to use as fuel.

The glassworks produced a range of different products, including bottles, window panes, and even glass globes for Benjamin Franklin’s experimental electrostatic machines.

Other small-scale industries

- William Bradford established a papermill near present-day Elizabeth, NJ, in 1726. This was built primarily to support the printing of his newspaper, the New York Gazette.

- New Jersey had large supplies of clay, especially along the Delaware River corridor, and this led to the establishment of a sizable brickmaking and pottery industry in the area.

- The New Jersey coast supported a strong fishing and oyster industry, and whaling was also performed from the colony in the mid-1600s until around the turn of the century. Whalers set up lookouts on bluffs in areas such as Cape May in southern New Jersey, before sending out small boats to harpoon the whale, club it to death, and bring it to shore. Whale oil was used for fuel or as lubricant, while whale baleen (which looked and felt similar to bone but was actually composed of keratin, the same material as fingernails) was used in clothing, including corsets and hats.

Labor

In its early years, the New Jersey economy predominantly relied on indentured servants to work on farms and docks, and to provide labor as it was needed in other industries in the colony.

Indentured servants were people who agreed to work for free for a set period in return for their transport to the Thirteen Colonies.

However, over time, labor demands grew, and New Jersey began importing slaves from Central and West Africa in the late 1600s.

There were already slaves in the colony from its time under Dutch control, but the practice began to grow in popularity in the first half of the 1700s. By 1738, there were an estimated 3,981 slaves in the colony.

The majority of New Jersey’s slaves worked on farms, but many worked as servants in houses, at lumberyards, and in bog iron production and mining as well.