Contents

Contents

New York Colony had a diverse, varied religious history, in large part due to the range of different groups that settled in the province under both Dutch and British rule.

New Netherland: the Dutch Reformed Church and Liberty of Conscience (1621-1664)

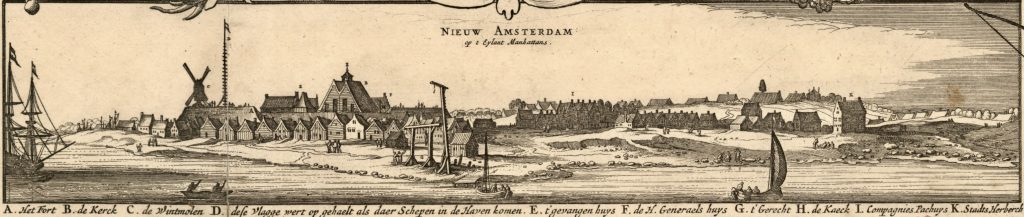

New York City was first settled in modern-day Manhattan and named New Amsterdam, existing within the Dutch colony of New Netherland. The settlement was founded by the Dutch West India Company (WIC) in 1621, which had been granted the sole right to operate trade in Dutch colonies throughout the New World.

The religion of New Netherland was influenced by two main factors: the WIC and religious tolerance in the Netherlands.

The WIC and the Dutch Reformed Church

When the WIC was chartered, the official religion of the Netherlands was the Dutch Reformed Church. This was a Calvinist Protestant denomination.

One of the purposes of the WIC was to spread the teachings of this Church. In New Netherland, the WIC therefore declared that the Dutch Reformed Church was the only denomination permitted to publicly practice their religion.

To promote the Church, the WIC ensured its religious holidays were observed and funded the organization, paying the salaries of church ministers in Manhattan as early as 1628. However, colonists would later have to fund the ministers’ salaries themselves.

Membership of the Dutch Reformed Church was strictly controlled and had onerous induction requirements, which only about 20% of the population could fulfill. Nevertheless, services at churches throughout the colony were well attended, even by those who were not members.

Religious Tolerance and Liberty of Conscience

Although the Dutch Reformed Church was the official religion in New Netherland, citizen worship was not mandated.

At the time, the Netherlands was remarkably diverse, and rejected the imposition of a single religion on its inhabitants. New Netherland largely mirrored this.

Some of the first settlers in New Netherland were Walloons, a group of French-speaking Protestants. Only about half of the population was ethnically Dutch, with the remainder made up of Franch, Germans, Scandinavians, and a small Jewish minority.

The WIC was generally pragmatic and profit-driven. Recognizing that enforcing religion could damage the economic growth of the colony by driving these people away, it adopted the Dutch concept of Liberty of Conscience.

Liberty of Conscience meant that people were free to practice other religions in their homes, but not publicly. Although this was progressive for the time, it was still heavily restrictive.

Significant minority communities of several different religions formed in New Amsterdam. Most would arrive together and form enclaves, i.e. insular communities, made up of their ethnicity and religion.

- Quakers: sometimes known as the Religious Society of Friends, a Protestant group.

- Jewish people, mainly from Brazil and Germany.

- Lutherans: Protestants, generally German, following the reform efforts of Martin Luther.

Since religion was such an important part of daily life at the time, the ban on public worship was very restrictive for these communities.

Persecution and the Flushing Remonstrance

In the mid-1650s, a new governor, Pieter Stuyvesant, came into power in New Netherland. He took a harder line against religious tolerance, leading to calls by Baptists, Lutherans, Jews, and Quakers for more freedoms.

The fear that this dissent could undermine the authority of the WIC led Stuyvesant to crack down. In 1656, the Dutch had William Wickenden, a Baptist minister, and William Hallett, sheriff of Flushing, arrested for baptizing Christians. Robert Hodgson was arrested for preaching Quakerism.

This increase in persecution was met with stronger calls for reform.

On 27 December 1657, 30 Dutch citizens in Flushing signed the Flushing Remonstrance. It called for the end of religious persecution in the colony and was mainly motivated by concern over the treatment of Quakers.

Stuyvesant’s response was swift, replacing the government of Flushing and arresting four signatories of the Remonstrance, three of whom were released after recanting the petition. In 1658, Stuyvesant banished a group of Quakers for attempting to convert others.

Shortly thereafter, John Bowne, an English settler in New Amsterdam, began to allow Quakers to meet on his property. He converted to Quakerism in 1659 and was arrested in 1662.

His sentence was banishment to the Dutch Republic, where he petitioned the directors of the WIC to order Stuyvesant to end religious persecution. They did so in 1663.

British Rule: Anglicanism, public tolerance and ‘irreligiousness’ (1664-1775)

Articles of Surrender

After taking over New Netherland in 1664 and renaming it New York, the English guaranteed the population “liberty of conscience in divine worship and church discipline”. The English further granted privileges to the people of New York, allowing existing Christian churches in the region to remain.

This meant the English did not impose their religion on the Dutch, force them to emigrate, or take their land, which would have been quite normal when taking over a colony at the time. As a result, there was no immediate overhaul of society and religion.

The Duke’s Laws and Catholic Tolerance

In 1665, Governor Richard Nicholls laid out the Duke’s Laws, which included provisions regarding religion. These did not differentiate between Protestant denominations, freeing Protestants to practice publicly.

Under the Duke’s Laws:

- Native Americans were discouraged from practicing their religion.

- Practice of Catholicism was banned.

- Each town was encouraged to have a minister and a Protestant church (regardless of denomination), which should be capable of holding 200 people.

- Procedures were provided for proof of religious qualifications by those purporting to be men of the church, and for the appointment of overseers and wardens of the church to provide for upkeep and salary for the minister via levies on the townspeople.

In 1674, Governor Sir Edmund Andros was directed by the Duke of York (who ruled the colony via his governors) to “permit all persons of what religion soever, quietly to inhabit within the precincts of your jurisdiction.”

The Duke may have intended this to introduce tolerance of Catholics in the colony, but there is little evidence that his instruction had this effect.

In 1683, Governor Thomas Dongan, an Irish Catholic, and the colonial assembly, passed the “Charter of Liberties and Privileges”. This allowed all Christians to practice their religion, and Dongan had English Catholic clerics open a school in New York and observe Mass.

Toleration of Catholics did not last. In 1688, the Glorious Revolution in England led to a crackdown on Catholic practice, which was also enforced in New York. The school was closed, and Dongan was removed from office.

In 1689, Jacob Leisler, a merchant and former WIC soldier, led a revolution against the governance of New York. His new government suspended “all Roman Catholics from Command and Places of Trust,” removing Catholics from public office.

In 1691, Leisler was removed by the new King of England and replaced with Governor William Sloughter. As a result, persecution of Catholics was entrenched, specifically rejecting the liberty of Catholics to worship.

Promotion of Anglicanism: the Ministry Act of 1693

In 1693, Governor Benjamin Fletcher wanted to improve the standing of the Church of England in New York. He ordered the Colonial Assembly to pass an Act providing for the creation and financial maintenance (by public taxation) of a sizable Anglican ministry in the colony.

The Assembly passed the Ministry Act that year, but intentionally did not specify that it provided only for an Anglican ministry.

Although this guaranteed at least one Protestant minister would be present in certain cities and counties of the colony, it did not force Anglicanism on people or restrict the practice of other religions. The popularity of Anglicanism grew as more settlers arrived from England, but this did not reduce tolerance of other religions in New York.

“Irreligious”

In a 1695 publication, the Reverend John Miller, an Episcopal minister, claimed that New York was “irreligious”. He argued that many of the colony’s ministers were unqualified, irresponsible, and harmed the reputation of religion and the Anglican church.

Miller complained that there was such a diversity of religions resisting the imposition of the Anglican church that the King should send an Anglican bishop and use force to crack down on other denominations. This, of course, did not happen.

Continuing Tolerance

Up until the American Revolution, New York Colony continued to allow a variety of denominations of Protestantism and Judaism to worship freely. Traditional communities continued to form enclaves, for example:

- Dutch immigration had reduced since the English takeover, meaning the resident Dutch population grew increasingly isolated and entrenched in their Dutch Reformed religion, even as the Netherlands itself evolved. The Dutch enclave in New York notably brought over the tradition of Sinterklaas, which evolved into Santa Claus.

- A large tranche of Lutheran German immigrants arrived in 1710 and maintained their religion, forming their own isolated community. They spoke German and married amongst themselves, with only some learning English to make business transactions easier.

- The Presbytery of New York was formed in 1717. In the 1720s and 1730s, an increase in Scottish and Irish immigration led to the growth of Presbyterianism, a Reformed Protestant denomination with roots in the teachings of the Scottish reformer John Knox.

The First Great Awakening

The “irreligiousness” observed by John Miller was not limited to New York. By the early 18th century, secularism was becoming more common throughout the Thirteen Colonies.

This led to calls from religious leaders for a return to devotion and piety. To draw people in, ministers adopted evangelism and public preaching about the consequences of the rejection of God.

In New York, this began mainly in the Dutch Reformed Church in the 1720s and 1730s, with the encouragement of Pietist minister Jacob Frelinghuysen. While many colonies saw mass gatherings in open spaces, the religious diversity of New York meant the early revival took place through smaller meetings.

George Whitefield, an Anglican priest, traveled the colonies starting in 1740. He visited New York multiple times and preached to large crowds, often to Presbyterians, despite his Anglican origins.

The revival led to a split in the Presbyterian church, known as the Old Side-New Side Controversy. The Old Side rejected the revival, wishing to maintain traditional religious practices, while the New Side embraced the changes and shifted in favor of evangelism and a focus on personal religious experience.

The Presbytery of New York ended up in the middle of the split, before siding with the New Side in 1745. They therefore left the Synod of Philadelphia and created the Synod of New York. In 1758, the two organizations reunited, creating the Synod of New York and Philadelphia, which had three times as many New Side ministers as Old Side ministers.

Catholicism

For Catholics, meanwhile, persecution continued. In 1700, under Governor Bellomont, an Act was passed requiring that Catholic priests depart the colony by November 1, 1700, or face the threat of life imprisonment.

In 1741, rumors of Catholic incitement of a slave revolt caused hatred and suspicion. John Ury, an Anglican, was executed in the false belief that he was a Catholic and a Spanish spy.

Nevertheless, some Catholics remained in New York. Ferdinand Steinmeyer, a German Jesuit (a type of cleric of the Catholic Church), led Mass for a Catholic community in New York City after 1756. The services were held in a variety of private places, such as houses.

Only after the Revolution was the 1700 law against Catholic priests repealed, allowing Catholic Mass to be held in public.

Judaism

The Jewish population continued to grow throughout the 1700s, as a mix of Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews.

The city’s first Jewish Synagogue, Congregation Shearith Israel, following the Sephardi tradition, gained its first building in 1730, although it had been founded originally in 1654.

The Jewish population reached around 300 in 1750. This was 2.3% of the population of New York City.

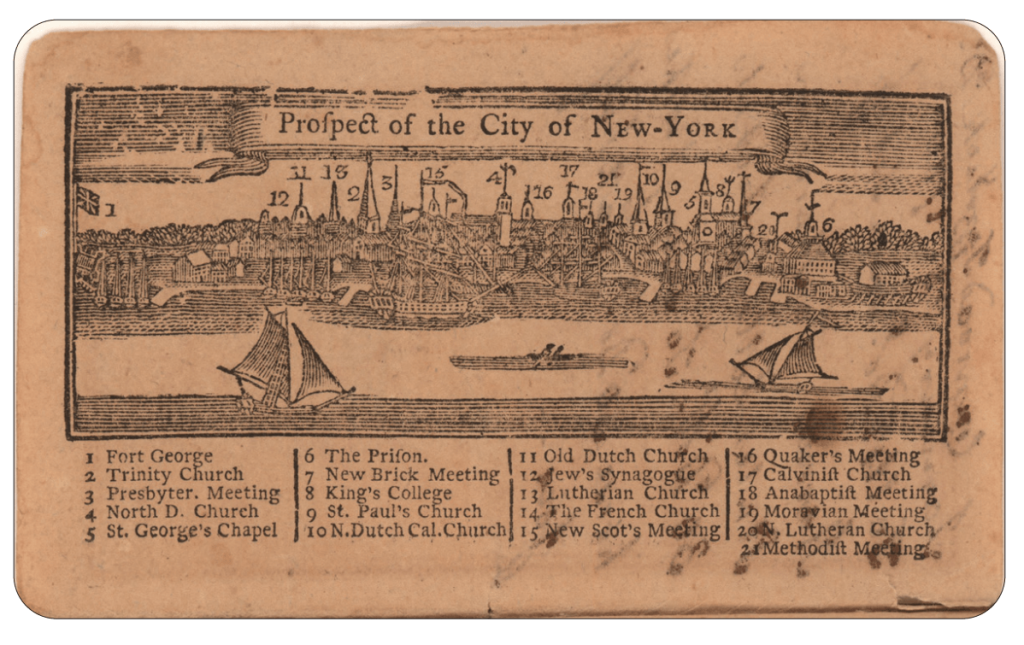

The above woodblock carving of the New York skyline highlights its religious diversity in 1771, showing churches of the Dutch Reformed, Anglican, Presbyterian, Lutheran, French Huguenot, Congregational, Methodist, Baptist, Quaker, Moravian, and Jewish faiths.

End of the Anglican Church

After the Revolution, the majority of Anglican clergymen in New York were Loyalists, which was unsurprising given that they had sworn allegiance to the King. Since prayers for the King and British Parliament, part of Anglican tradition, began to be seen as treason after the Declaration of Independence, change was necessary.

Therefore, in 1784 and 1785, the Episcopal church of the United States was formed. Its clergy, mainly former Church of England members, met in New York and Philadelphia to draft a constitution for the Episcopal Church to maintain the Anglican tradition while removing its devotion to the British.

In 1787, Samuel Provoost, an Anglican priest born in New York who had supported American independence, was consecrated by the Anglican establishment in England as the first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York.

The Episcopal Church preserved many of the beliefs of the Anglican Church and was formed as its direct evolution, but rejected the Anglican devotion to the British.