Contents

Contents

North Carolina was officially an Anglican colony. However, in practice, there was strong freedom of religion in the settlement, and Quakers became a dominant force in the colony’s early history, despite a period of conflict with Anglican sects around the turn of the 1700s.

Founding

In 1663, King Charles II issued a land grant to eight Lords Proprietors in British North America, covering territory that would later become North Carolina.

Initially, North and South Carolina were a single region, called the Province of Carolina.

The early administration of and life in the colony were relatively disorganized, and this was reflected in North Carolina’s religious makeup.

By law, the Church of England was officially established as the religion of the colony. However, settlements were spread out, and Anglican infrastructure was weak, meaning that in reality, religion was practiced informally by local laypeople in each town or village.

Though there was an official religion, the 1669 Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina provided for the acceptance of various different religions, including those outside of Christianity, for the sake of the prosperity of the colony.

But since the natives of that place, who will be concerned in our plantation, are utterly strangers to Christianity, whose idolatry, ignorance, or mistake gives us no right to expel or use them ill; and those who remove from other parts to plant there will unavoidably be of different opinions concerning matters of religion, the liberty whereof they will expect to have allowed them, and it will not be reasonable for us, on this account, to keep them out, that civil peace may be maintained amidst diversity of opinions, and our agreement and compact with all men may be duly and faithfully observed… and also that Jews, heathens, and other dissenters from the purity of Christian religion may not be scared and kept at a distance from it, but, by having an opportunity of acquainting themselves with the truth and reasonableness of its doctrines, and the peaceableness and inoffensiveness of its professors, may, by good usage and persuasion, and all those convincing methods of gentleness and meekness, suitable to the rules and design of the gospel, be won ever to embrace and unfeignedly receive the truth; therefore, any seven or more persons agreeing in any religion, shall constitute a church or profession, to which they shall give some name, to distinguish it from others.

This allowed various religious groups to establish themselves in the colony, including after North and South Carolina were each assigned their own deputy governors in 1691.

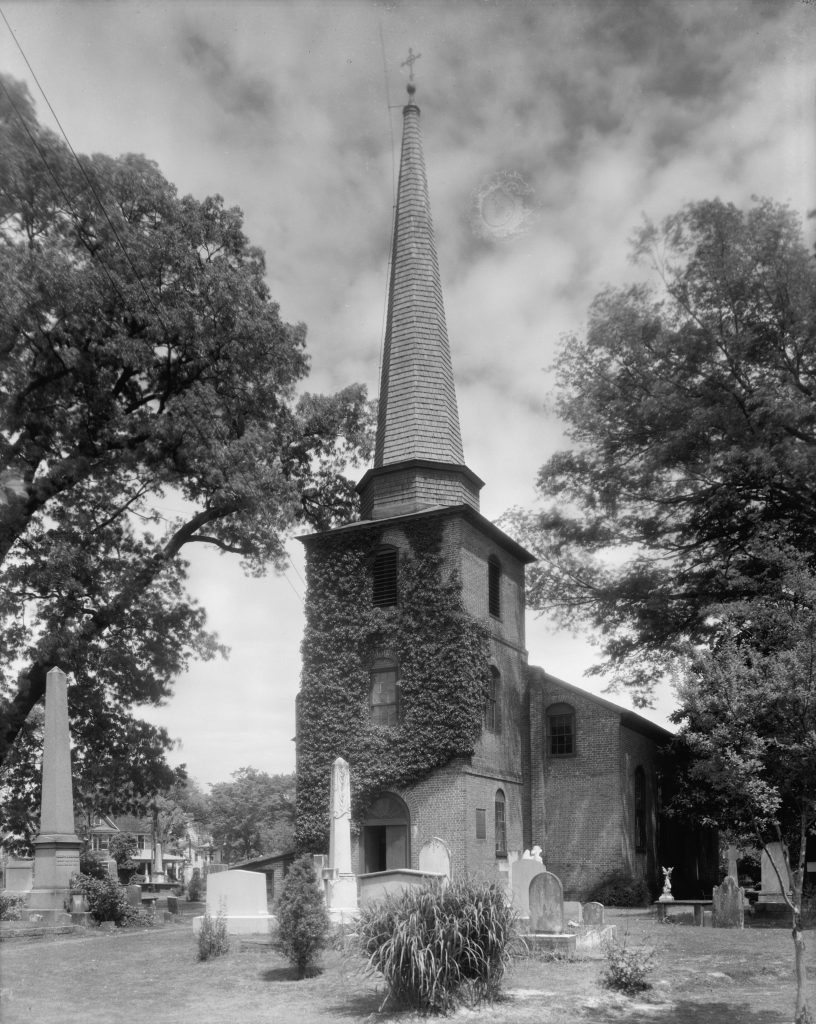

Initially, there were some Anglican congregations, but there was a lack of ministers and clergymen, and very few churches existed.

In the late 1600s, large numbers of Quakers emigrated to North Carolina, especially around the Albemarle region. They were attracted to the colony for its religious freedom, often escaping other parts of British North America that persecuted Quakers for their beliefs.

By the 1690s, Quakers had become the dominant religion in North Carolina, including in government. In 1694, John Archdale, a Quaker, became governor of Carolina.

Religious conflict at the turn of the century

In the early 1700s, as North Carolina’s population grew, and its governance and administration became more organized, Anglicans fought with Quakers for political control of the colony.

Henderson Walker, an Anglican, was placed in charge of North Carolina in 1699. He soon established Anglicanism as the official religion of the colony, and implemented the Vestry Act in 1701, levying mandatory taxes on all citizens to help fund Church of England parishes.

Quakers soon regained control of the legislative assembly and repealed the Vestry Act, but conflict continued between the two sides. In 1703, Sir Nathaniel Johnson passed a law excluding religious dissenters (non-Anglicans) from Carolina, which, fortunately for the Quakers, the assembly also soon repealed.

In 1704, when Queen Anne ascended the throne in England, colonial politicians were required to swear an oath to the Crown. However, Quakers are morally opposed to swearing oaths, instead choosing to affirm their allegiances.

This was not allowed under colonial law, so all Quakers lost their positions in the Carolina assembly. However, the law requiring oaths was repealed in 1708, once again making it possible for Quakers to participate in politics.

Cary’s Rebellion

In 1711, this conflict between Anglican and Quaker-aligned factions came to a head in an armed conflict known as Cary’s Rebellion.

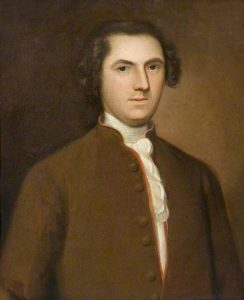

Thomas Cary was the deputy governor of North Carolina from 1705 to 1706, and again from 1708 to 1711. During his second term, he predominantly sided with Quakers on local political issues, such as allowing their politicians to affirm rather than swear an oath to take office.

In early 1711, the Lords Proprietors sent Edward Hyde to take over the role of deputy governor from Cary. Cary had lowered rent rates that settlers owed the proprietors to use their land (known as quitrents) in Bath County, and he was not their choice to lead the colony, having come to power through factional maneuvering.

Seeing that Hyde would side with the Anglican faction, Cary refused to hand over his position, citing the fact that the Carolina Governor could not officially confirm the appointment, as he had died recently.

Hyde then organized a force to try and capture Cary, who went into hiding, but was able to raise a small army of his own to fight Hyde’s men. This led to a series of small-scale battles, before Virginia sent military assistance to Hyde, eventually forcing Cary to flee North Carolina. He was captured and sent to England, but was not prosecuted for his actions.

Religious conflict continued in Carolina, but died down once the province was officially split into North and South in 1712.

Mid to late 1700s: regional religious diversity

From this point onwards, North Carolina continued to host a wide range of different religious sects, most of which called a specific part of the colony home.

The Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s led to an increase in popularity of evangelical forms of Protestantism, especially in inland areas where the Church of England was less established.

This period of religious revival laid the groundwork for an explosion in popularity of the Baptist movement in the middle of the century, centered around Sandy Creek Baptist Church, which was established in 1755.

The Baptists’ emphasis on individualism resonated strongly with the colonists, causing it to quickly take hold in the North Carolina backcountry.

These inland regions, such as along the Piedmont, also became home to a range of European migrants, who moved to North Carolina throughout the 1700s.

- Scottish/Irish settlers were predominantly Presbyterian.

- German settlers were members of the Lutheran and Reformed Churches.

- Moravians (a Protestant denomination whose members mostly originated from Germany and the Czech Republic) settled around the Wachovia Tract, around the modern-day area of Forsyth County.

As the 1700s progressed, Quaker influence declined as military conflict became more commonplace in North Carolina, beginning with informal skirmishes and battles between colonists and native populations, followed by the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the North Carolina War of Regulation (1766-1771), and eventually the American Revolution.

The Quakers were pacifists, refusing to fight in wars, and resigning in protest when military actions were funded or authorized. Though their political influence waned, large numbers of Quakers continued to live in the Albemarle and Bath County regions of the colony.

Eastern coastal areas continued to be dominated by Anglicans, and they slowly became the dominant religious force in North Carolina as Quaker influence declined. However, Anglican parishes continued to suffer from staffing and resource shortages up until the Revolutionary War.