Contents

Contents

The colonial Pennsylvania economy was diverse, though it had a particularly heavy emphasis on staple food crops such as wheat and maize.

Agriculture

The soil in Pennsylvania was particularly fertile compared to elsewhere in the Thirteen Colonies, especially New England, which suffered from rocky soils and harsh winters.

While the Southern Colonies’ plantations primarily focused on cash crops such as tobacco, Pennsylvania produced large amounts of staple food crops, such as wheat, rye, and corn, much of which was sold to other colonies or exported to Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Thanks to the amount of food it produced, Pennsylvania was known as the “breadbasket” of the New World, alongside the other Middle Colonies (New York, New Jersey, and Delaware).

Flour was milled locally and exported in large quantities, and was the largest single economic output in Pennsylvania during the colonial period.

Farmers predominantly owned their own land rather than leasing it, and would also raise livestock such as pigs, cows, and sheep.

These farmers would often use indentured servants as laborers, who agreed to work for free for a specific period of time in return for their passage to North America.

African slave labor was also used, though this was less common than in the Southern Colonies or in provinces with large numbers of leasehold farms on large manors, such as New York.

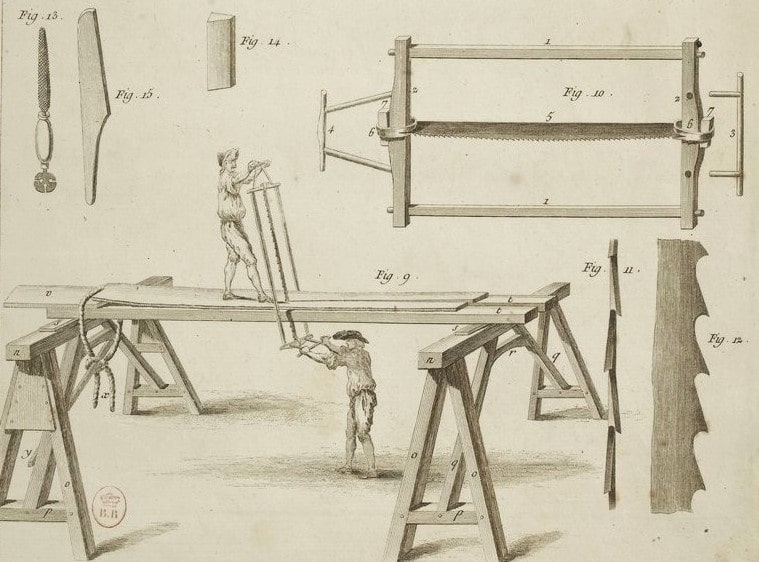

Lumber and forestry products

The Province of Pennsylvania had access to large amounts of forests, leading to the establishment of a thriving lumber industry.

The industry began around Philadelphia and its surrounding counties, before moving out into the interior of the colony, especially along the Delaware River, as local timber supplies were depleted by logging.

The harvested timber was processed at sawmills in Philadelphia and then exported as a raw material, predominantly to Europe, or used in a wide variety of different end products, such as ship hulls and masts, barrels, and houses.

Wood was also used as charcoal to fuel iron furnaces in Pennsylvania or burned to create potash – a highly sought-after industrial chemical in the colonies and in Europe at the time.

Maritime trade and shipbuilding

Most of Pennsylvania’s exports passed through the Port of Philadelphia, which became a hub of maritime trade.

For merchants, Philadelphia Harbor was perfectly positioned on the Delaware River, providing quick access to large population centers throughout the Middle Colonies. As a result, the port became increasingly active throughout the colonial era, surpassing Boston as the busiest port in British North America in the 1750s.

The port helped support a wide range of ancillary industries, such as warehousing and ropewalks – large buildings where rope would be cut, twisted, and finished for use on ships’ rigging.

Philadelphia was also a leader when it came to shipbuilding. The colony had ample access to large amounts of good-quality lumber, as well as a thriving port and large amounts of shipbuilding talent.

As the Revolutionary War started, Philadelphia was instrumental in building gunboats and frigates for the Continental Navy, such as the famous USS Randolph, except during its occupation by the British from September 1777 to June 1778.

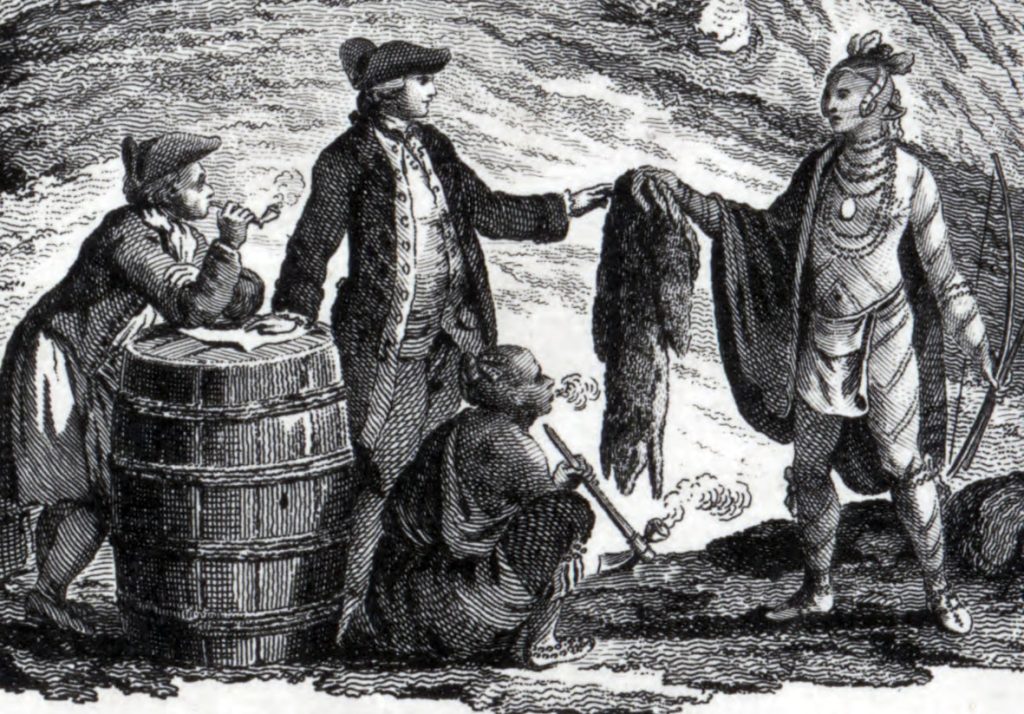

Fur

During its early history in particular, Pennsylvania fur traders would turn a profit by exchanging food, textiles, and weapons with Native American tribes in return for animal pelts, especially from beavers and otters.

These furs could then be exported to Europe and sold as fashion items, often for a considerable price.

Soon though, the fur trading industry suffered from issues with overhunting, leading hunters to search inland for greater numbers of beavers, otters, foxes, and even bears, leading to longer expeditions and fewer furs available to sell.

As early as 1700, declines in animal populations led to a decline in the fur trade more broadly in Pennsylvania, and the colony began to focus more on other industries instead.

Iron

Like many of the other Middle Colonies, Pennsylvania had a strong iron industry beginning in the early 1700s.

Iron ore was mined locally throughout the colony, with major deposits including the Cornwall Ore Banks (Lebanon County) and along the Schuylkill Highlands in Berks and Chester Counties.

The metal was processed locally at furnaces and forges in Pennsylvania, supporting a diverse industry of mining and processing, often located near the mine sites.

Initially, finished iron products such as barrel hoops, anchors, and buckles were manufactured domestically. However, after the British passed the Iron Act to protect their domestic ironmaking industry, the metal was more often exported as a raw material – specifically as ingots of pig or bar iron.

To learn more, read our article on the broader economy of the Middle Colonies.