Contents

Contents

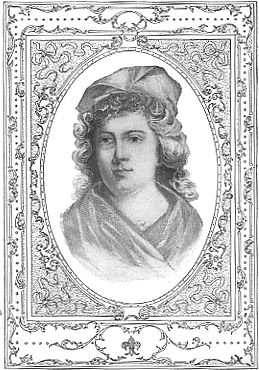

Sarah, the only daughter of Benjamin Franklin, was born at Philadelphia on the eleventh of September, 1744. Of her early years no particulars can now be obtained; but from her father’s appreciation of the importance of education, and the intelligence and information that she displayed through life, we may presume that her studies were as extensive as were then pursued by females in any of the American colonies.

In 1764, she was called to part with her father, who was sent to Europe for the first time in a representative capacity. The people of Pennsylvania were at that time divided into two parties – the supporters and the opponents of the proprietaries. The sons of Penn, as is known, had left the religion of their father, and joined the Church of England; and the bulk of that persuasion were of the proprietary party. The mass of the Quakers were in opposition, and with them Franklin had acted. After having been for fourteen years a member of the Assembly, he lost his election to that body in the autumn Of 1764, by a few votes; but his friends being in the majority in the House, immediately elected him the agent of the province in England.

The proprietary party made great opposition to his appointment; and an incident occurred in connection with it that shows us how curiously the affairs of Church and State were intermingled in those days. A petition or remonstrance to the Assembly against his being chosen agent, was laid for signature upon the communion-table of Christ Church, in which he was a pew-holder, and his wife a communicant. His daughter appears to have resented this outrage upon decency and the feelings of her family, and to have spoken of leaving the church in consequence; which gave occasion to the following dissuasive in the letter which her father wrote to her from Reedy Island, November 8th, 1764, on his way to Europe: “Go constantly to church whoever preaches. The act of devotion in the common prayer-book is your principal business there; and if properly attended to, will do more towards amending the heart than sermons generally can do; for they were composed by men of much greater piety and wisdom than our common composers of sermons can pretend to be; and therefore I wish you would never miss the prayer days. Yet I do not mean you should despise sermons, even of the preachers you dislike, for the discourse is often much better than the man, as sweet and clear waters come through very dirty earth. I am the more particular on this head, as you seemed to express a little before I came away some inclination to leave our church, which I would not have you do.”

The opinion entertained by many that a disposition to mobbing is of modern growth in this country is erroneous. In Colonial times outrages of this character were at least as frequent as now. Dr. Franklin had not been gone a year before his house was threatened with an attack. Mrs. Franklin sent her daughter to Governor Franklin’s in Burlington, and proceeded to make preparation for the defence of her castle. Her letter detailing the particulars may be found in the last edition of Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia.

The first letter from Sarah Franklin to her father that has been preserved, was written after her reum from this visit to Burlington. In it she says: “The subject now is Stamp Act, and nothing else is talked of. The Dutch talk of the ‘Stamp tack,’ the negroes of the ‘tamp’ – in short, every body has something to say.” The commissions which follow for gloves, lavender, and tooth-powder give us a humble idea of the state of the supplies in the Colonies at that day. The letter thus concludes: “There is not a young lady of my acquaintance but what desires to be remembered to you. I am, my dear, your very dutiful daughter,

SALLY FRANKLIN”

In a letter dated on the 23d of the following March (1765), the Stamp Act is again mentioned: “We have heard by a round-about way that the Stamp Act is repealed. The people seem determined to believe it, though it came from Ireland to Maryland. The bells rung, we had bonfires, and one house was illuminated. Indeed I never heard so much noise in my life; the very children seem distracted. I hope and pray the noise may be true.”

A letter to her brother, written September 30th, 1766, speaks thus of some political movements in Philadelphia at that time: ” The letter from Mr. Sergeant was to Daniel Wistar. I send you the Dutch paper, where I think there is something about it. On Friday night there was a meeting of seven or eight hundred men in Hare’s brew-house, where Mr. Ross, mounted on a bag of grain, spoke to them a considerable time. He read Sergeant’s letter, and some others, wh ich had a good effect, as they satisfied many. Some of the people say he outdid Whitfield; and Sir John says he is in a direct line from Solomon. He spoke several things in favor of his absent friend, whom he called the good, the worthy Dr. Franklin, and his worthy friend. After he was gone, Hugh Roberts stood up and proposed him in Willing’s place, and desired those who were for him to stand up; and they all rose to a man.”

On the 29th of October, 1767, Sarah Franklin was married to Richard Bache, a merchant of Philadelphia, and a native of Settle, in Yorkshire, England. After their marriage, Mr. and Mrs. Bache appear to have resided with Mrs. Franklin in the house built by her in the year 1765, upon ground over which Franklin Place now runs. This house, in which Franklin died, stood rather nearer to Chestnut Street than to Market Street. The original entrance to it was over the ground upon which No. 112 Market Street is now built. On Franklin’s return from Europe, he opened a new entrance to it between Nos. 106 and 108, under the archway still remaining, the house No. 106, and that lately No. 108, being built by him. His house was torn down about the year 1813, when Franklin Court was built upon the ground occupied by it, the court in front and the garden in the rear.

Mrs. Franklin died on the 19th of December, 1774, having been attacked by paralysis four days previously. The mansion house continued to be occupied by Mr. Bache and his family. In the garden a willow tree was planted by Mrs. Bache on the 4th of July, 1776.

The approach of the British army through New Jersey in December, 1776 induced Mr. Bache to remove his family to Goshen township in Chester County, from which place the following letter was addressed by Mrs. Bache to her father, who, in the previous October, had been sent to France by the American Congress. Mrs. Bache’s eldest son accompanied him, and was educated in France and Geneva under the supervision of his grandfather.

“GOSHEN, February 23d, 1777

HONORED SIR –

We have been impatiently waiting to hear of your arrival for some time. It was seventeen weeks yesterday since you left us – a day I shall never forget. How happy shall we be to hear you are all safe arrived and well. You had not left us long before we were obliged to leave town. I never shall forget nor forgive them for turning me out of house and home in the middle of winter, and we are still about twenty-four miles from Philadelphia, in Chester County, the next plantation to where Mr. Ashbridge used to live. We have two comfortable rooms, and we are as happily situated as I can be, separated from Mr. Bache; he comes to see us as often as his business will permit. Your library we sent out of town well packed in boxes, a week before us, and all the valuable things, mahogany excepted, we brought with us. There was such confusion that it was a hard matter to get out at any rate; when we shall get back again I know not, though things are altered much in our favor since we left town. I think I shall never be afraid of staying in it again, if the enemy were only three miles instead of thirty from it, since our cowards, as Lord Sandwich calls them, are so ready to turn out against those heroes who were to conquer all before them, but have found themselves so much mistaken; their courage never brought them to Trenton, till they heard our army were disbanded. I send you the newspapers; but as they do not always speak true, and as there may be some particulars in Mr. Bache’s letters to me that are not in them, I will copy those parts of his letters that contain the news. I think you will have it more regular.

“Aunt has wrote to you, and sent it to town. She is very well, and desires her love to you and Temple. We have wished much for him here when we have been a little dull; he would have seen some characters here quite new to him. It’s lucky for us Mr. George Clymer’s, Mr. Meredith’s, and Mr. Budden’s families are moved so near us. They are sensible and agreeable people, and are not often alone. I have refused dining at Mr. Clymer’s today, that I might have the pleasure of writing to you and my dear boy, who, I hope, behaves so as to make you love him. We used to think he gave little trouble at home; but that was, perhaps, a mother’s partiality. I am in great hopes that the first letter of Mr. Bache will bring me news of your arrival. I shall then have cause to rejoice.

I am, my dear papa, as much as ever, your dutiful and affectionate daughter.

S. BACHE.”

Mrs. Bache returned home with her family shortly after, but in the following autumn the approach of the British army after their victory on the Brandywine, again drove them from Philadelphia. On the 17th of September, 1777, four days after the birth of her second daughter, Mrs. Bache left town, taking refuge at first in the hospitable mansion of her friend Mrs. Duffield, in Lower Dublin Township, Philadelphia County. They afterwards removed to Manheim Township in Lancaster County where they remained until the evacuation of Philadelphia by the British forces. The following extracts are from letters written to Dr. Franklin after their return. On the 14th July, 1778, Mr. Bache writes: “Once more I have the happiness of addressing you from this dearly beloved city, after having been kept out of it more than nine months. . . . I found your house and furniture upon my return to town, in much better order than I had reason to expect from the hands of such a rapacious crew; they stole and carried off with them some of your musical instruments, viz: a Welsh harp, ball harp, the set of tuned bells which were in a box, viol-&-gamba, all the spare armonica glasses and one or two spare cases. Your armonica is safe. They took likewise the few books that were left behind, the chief of which were Temple’s school books. and the History of the Arts and Sciences in French, which is a great loss to the public; some of your electric apparatus is missing also – a Captain André also took with him the picture of you which hung in the dining-room. The rest of the pictures are safe and met with no damage, except the frame of Alfred, which is broken to pieces.” The postscript to this letter is curious. “I wish I could have sent to me from France two dozen of padlocks and, keys fit for mails, and a dozen post-horns; they are not to be had here.”

André was quartered in Franklin’s house during the sojourn of the British in Philadelphia. In the following letter from Mrs. Bache, his future acquaintance Arnold is mentioned. It is dated October 22, 1778, Mrs. Bache having remained at Manheim with her children until the autumn. “This is the first opportunity I have had since my return home of writing to you. We found the house and furniture in much better order than we could expect, which was owing to the care the Miss Cliftons took of all we left behind; my being removed four days after my little girl was born, made it impossible for me to remove half the things we did in our former flight.” After describing her little girl, she adds: “I would give a good deal if you could see her; you can’t think how fond of kissing she is, and gives such old-fashioned smacks, General Arnold says he would give a good deal to have her for a school mistress, to teach the young ladies how to kiss.” . . . There is hardly such a thing as living in town, everything is so high, the money is old tenor to all intents and purposes. If I was to mention the prices of the common necessaries of life it would astonish you. , I have been all amazement since my return; such an odds have two years made, that I can scarcely believe I am in Philadelphia. . . . They really ask me six dollars for a pair of gloves, and I have been obliged to pay fifteen pounds for a common calamanco petticoat without quilting, that I once could have got for fifteen shillings.”

These high prices were owing to the depreciation of the continental money, but it subsequently was much greater. The time came when Mrs. Bache’s domestics were obliged to take two baskets with them to market, one empty to contain the provisions they purchased, the other full of continental money to pay for them.

On the 17th of January, 1779, after speaking of the continued rise of prices, she writes, that “there never was so much dressing and pleasure going on; old friends meeting again, the whigs in high spirits and strangers of distinction among us.” Speaking of her having met with General and Mrs. Washington several times, she adds: “He always inquires after you in the most affectionate manner, and speaks of you highly. We danced at Mrs. Powell’s on your birthday, or night I should say, in company together, and he told me it was the anniversary of his marriage; it was just twenty years that night.”

With this letter a piece of American silk was sent as a present to the queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

Dr. Franklin in his reply seems to have expressed some dissatisfaction at the gaiety of his countrymen, which he considered unseasonable. Mrs. Bache thus excuses herself for participating in it in a letter dated September 14, 1779: “I am indeed much obliged to you for your very kind present. It never could have come at a more seasonable time, and particularly so as they are all necessary. . . . But how could my dear papa give me so severe a reprimand for wishing a little finery. He would not, I am sure, if he knew how much I have felt it. Last winter was a season of triumph to the whigs, and they spent it gaily. You would not have had me, I am sure, stay away from the Ambassador’s or General’s entertainments, nor when I was invited to spend the day with General Washington and his lady; and you would have been the last person, I am sure, to have wished to see me dressed with singularity. Though I never loved dress so much as to wish to be particularly fine, yet I never will go out when I cannot appear so as to do credit to my family and husband. I can assure my dear papa that industry in this country is by no means laid aside; but as to spinning linen, we cannot think of that till we have got that wove which we spun three years ago. Mr. Duffield has bribed a weaver that lives on his farm to weave me eighteen yards, by making him three or four shuttles for nothing, and keeping it a secret from the country people, who will not suffer them to weave for those in town. This is the third weaver’s it has been at, and many fair promises I have had about it. ‘Tis now done and whitening, but forty yards of the best remains at Liditz yet, that I was to have had home a twelvemonth

last month. Mrs. Keppele, who is gone to Lancaster, is to try to get it done there for me; but not a thread will they weave but for hard money. My maid is now spinning wool for winter stockings for the whole family, which will be no difficulty in the manufactory, as I knit them myself. I only mention these things that you may see that balls are not the only reason that the wheel is laid aside. . . . This winter approaches with so many horrors that I shall not want anything to go abroad in, if I can be comfortable at home. My spirits, which I have kept up during my being drove about from place to place, much better than most people’s I meet with, have been lowered by nothing but the depreciation of the money, which has been amazing lately, so that home will be the place for me this winter, as I cannot get a common winter cloak and hat but just decent under two hundred pounds; as to gauze now, it is fifty dollars a yard; ’tis beyond my wish, and I should think it not only a shame but a sin to buy it if I had millions. It is indeed, as you say, that money is too cheap; for there are so many people that are not used to have it, nor know the proper use of it, that get so much, that they care not whether they give one dollar or a hundred for anything they want; but to those whose every dollar is the same as a silver one, which is our case, it is particularly hard; for Mr. Bache could not bear to do business in the manner it has been done in this place, which has been almost all by monopolizing and forestalling.”

In the patriotic effort of the ladies of Philadelphia to furnish the destitute American soldiers with money and clothing during the year 1780, Mrs. Bache took a very active part. After the death of Mrs. Reed, the duty of completing the collections and contributions devolved on her and four other ladies, as a sort of Executive Committee. The shirts provided were cut out at her house. A letter to Dr. Franklin, a part of which has been published, shows how earnestly she was engaged in the work. The Marquis de Chastellux thus describes a visit which he paid her about this time: “After this slight repast, which only lasted an hour and a half, we went to visit the ladies, agreeable to the Philadelphia custom, where the morning is the most proper hour for paying visits. . We began by Mrs. Bache. She merited all the anxiety we had to see her, for she is the daughter of Mr. Franklin. Simple in her manners, like her respected father, she possesses his benevolence. She conducted us into a room filled with work, lately finished by the ladies of Philadelphia. This work consisted neither of embroidered tambour waistcoats, nor of net-work edging, nor of gold and silver brocade. It was a quantity of shirts for the soldiers of Pennsylvania. The ladies bought the linen from their own private purses, and took a pleasure in cutting them out and sewing them themselves. On each shirt was the name of the married or unmarried lady who made it; and they amounted to twenty-two hundred.”

Mrs. Bache writes to Mrs. Meredith at Trenton: “I am happy to have it in my power to tell you that the sums given by the good women of Philadelphia for the benefit of the army have been much greater than could be expected, and given with so much cheerfulness and so many blessings, that it was rather a pleasing than a painful task to call for it. I write to claim you as a Philadelphian, and shall think myself honored in your donation.”

A letter of M. de Marbois to Dr. Franklin, the succeeding year thus speaks of his daughter: “If there are in Europe any women who need a model of attachment to domestic duties and love for their country, Mrs. Bache may be pointed out to them as such. She passed a part of the last year In exertions to rouse the zeal of the Pennsylvania ladies, and she made on this occasion such a happy use of the eloquence which you know she possesses, that a large part of the American army was provided with shirts, bought with their money, or made by their hands. In her applications for this purpose, she showed the most indefatigable zeal, the most unwearied perseverance, and a courage in asking, which surpassed even the obstinate reluctance of the Quakers in refusing.”

The letters of Mrs. Bache show much force of character, and an ardent, generous and impulsive nature. She has a strong remembrance of kindness, and attachment to her friends; and in writing to her father her veneration for him is ever apparent, combined with the confidence and affection of a devoted daughter. Her beloved children are continually the theme on which her pen delights to dwell. Again and again the little family group is described to her father when abroad; and it is pleasing to dwell on the picture of the great philosopher and statesman reading with parental interest domestic details like the following; “Willy begins to learn his book very well, and has an extraordinary memory. He has learned, these last holidays, the speech of Anthony over Caesar’s body, which he can scarcely speak without tears. When Betsy looks at your picture here, she wishes her grandpapa had teeth, that he might be able to talk to her; and has frequently tried to tempt you to walk out of the frame with a piece of apple pie, the thing of all others she likes best. Louis is remarkable for his sweet temper and good spirits.” To her son she says: “There is nothing would make me happier than your making a good and useful man. Every instruction with regard to your morals and learning I am sure you have from your grandpapa: I shall therefore only add my prayers that all he recommends may be strictly attended to.”

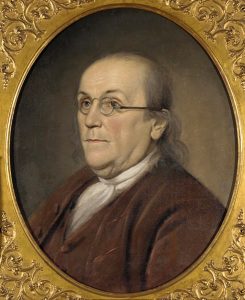

In September, 1785, after an absence of nearly seven years at the Court of France, Dr. Franklin returned to his home in Philadelphia. He spent the last years of his life amidst the family of his daughter and the descendants of the friends of his early years, the most of whom he had survived.

In 1792 Mr. and Mrs. Bache visited England, and would have extended their tour to France, had it not been for the increasing troubles of the French Revolution. They were absent about a year.

Mr. Bache, having relinquished commercial pursuits, removed in 1794 to a farm upon the river Delaware, sixteen miles above Philadelphia, which he named Settle, after his birthplace. Here they spent upwards of thirteen years, making their residence the seat of hospitality.

In 1807, Mrs. Bache was attacked by cancer, and removed to P hiladelphia in the winter of 1807-8, for the benefit of medical attendance. Her disease proved incurable, and on the 5th of October,1808, she died in the house in Franklin Court, aged sixty-four years. Her remains, with those of her husband, who survived her a few years only, are interred in the Christ Church burial-ground, beside those of her parents.

In person, Mrs. Bache was rather above the middle height, and in the latter years of her life she became very stout. Her complexion was uncommonly fair, with much color; her hair brown, and her eyes blue, like those of her father.

Strong good sense, and a ready flow of wit, were among the most striking features of her mind. Her benevolence was very great, and her generosity and liberality were eminent. Her friends ever cherished a warm affection for her.

It has been related that her father, with a view of accustoming her to bear disappointments with patience, was sometimes accustomed to request her to remain at home, and spend the evening over the chess-board, when she was on the point of going out to some meeting of her young friends. The cheerfulness which she displayed in every turn of fortune, proves that this discipline was not without its good effect.

Many of her witticisms have been remembered, but most of them, owing to the local nature of the events which gave rise to them and their mention of individuals, would not now bear being repeated. Her remark that “she hated all the Carolinians from Bee to Izard,” would be excluded for the latter reason, but may perhaps be excused here, as it has already appeared in print. What offence Mr. Bee had given, is not known, but Mr. lzard’s hostility to her father was of the most malignant character.

She took a great interest through life in political affairs, and was a zealous republican. Having learnt that the English lady to whom some of her daughters were sent to school, had placed the pupils connected with persons in public life, (her children among the number), at the upper end of the table, upon the ground that the young ladies of rank should sit together, Mrs. Bache sent her word that in this country there was no rank but rank mutton.

Mrs. Bache had eight children, of whom her eldest daughter died very young, and her eldest son in 1798 of the yellow fever, then prevailing in Philadelphia. Three sons and three daughters survived her.