Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 24 December 1737 in Groton, Connecticut.

- Silas Deane was an American diplomat and politician, serving as one of the first foreign diplomats from the United States to France during the American Revolutionary War.

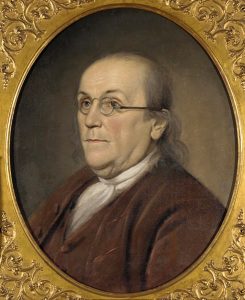

- He played a crucial role in securing French military aid for the American cause, working alongside Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee in Paris.

- Deane was instrumental in the negotiations that led to the signing of the Treaty of Alliance with France in 1778, a key turning point in the war.

- He helped recruit European military officers, such as the Marquis de Lafayette and Baron von Steuben, who became significant figures in the American war effort.

- Despite his contributions, Deane’s career was marred by accusations of financial mismanagement and political intrigue, leading to a fall from grace.

- He was eventually discredited and faced financial ruin, leading to a life in exile and a mysterious death in 1789.

- Died: 23 September 1789 aboard the Boston Packet, sailing from London.

- Buried in an unmarked grave in Deal, England.

Biography

Silas Dean, American diplomat, was born in Groton, Connecticut, in 1737. He graduated at Yale in 1758; in 1761 was admitted to the bar, but instead of practicing he became a merchant at Wethersfield, Connecticut. He took an active part in the movements in Connecticut preceding the American Revolution, and from 1774 to 1776 he was a delegate to the first and second Continental Congresses.

Early in 1776 he was sent to France by Congress, in a semi-official capacity, as a secret agent to induce the French government to lend its financial aid to the colonies. Subsequently he became, with Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee, one of the regularly accredited commissioners to France from Congress. On arriving in Paris, Deane at once opened negotiations with the French Foreign Minister, comte de Vergennes, and the playwright, Beaumarchais, securing through the latter the shipment of many vessel loads of arms and munitions of war to America. He also enlisted the services of a number of Continental soldiers of fortune, among whom were Lafayette, Baron Johann De Kalb and Thomas Conway. His carelessness in keeping account of his receipts and expenditures, and the differences between himself and Arthur Lee regarding the contracts with Beaumarchais, eventually led, in November 1777, to his recall to face charges, of which Lee’s complaints formed the basis. Before returning to America, however; he signed on 6 February 1778 the treaties of amity and commerce and of alliance which he and the other commissioners had successfully negotiated.

In America he was defended by John Jay and John Adams, and after stating his case to Congress was allowed to return to Paris (1781) to settle his affairs. Differences with various French officials led to his retirement to Holland, where he remained until after the treaty of peace had been signed, when he settled in England.

The publication of some intercepted

letters in Rivington’s Royal Gazette in New York (1781), in which Deane declared his belief that the struggle for independence was hopeless and counselled a return to British allegiance, aroused such animosity against him in America that for some years he remained in England. He died on shipboard in Deal harbor, England, on 23 September 1789, after having embarked for America on a Boston packet. No evidence of his dishonesty was ever discovered, and Congress recognized the validity of his claims by voting $37,000 to his heirs in 1842.