Contents

Contents

Quick facts

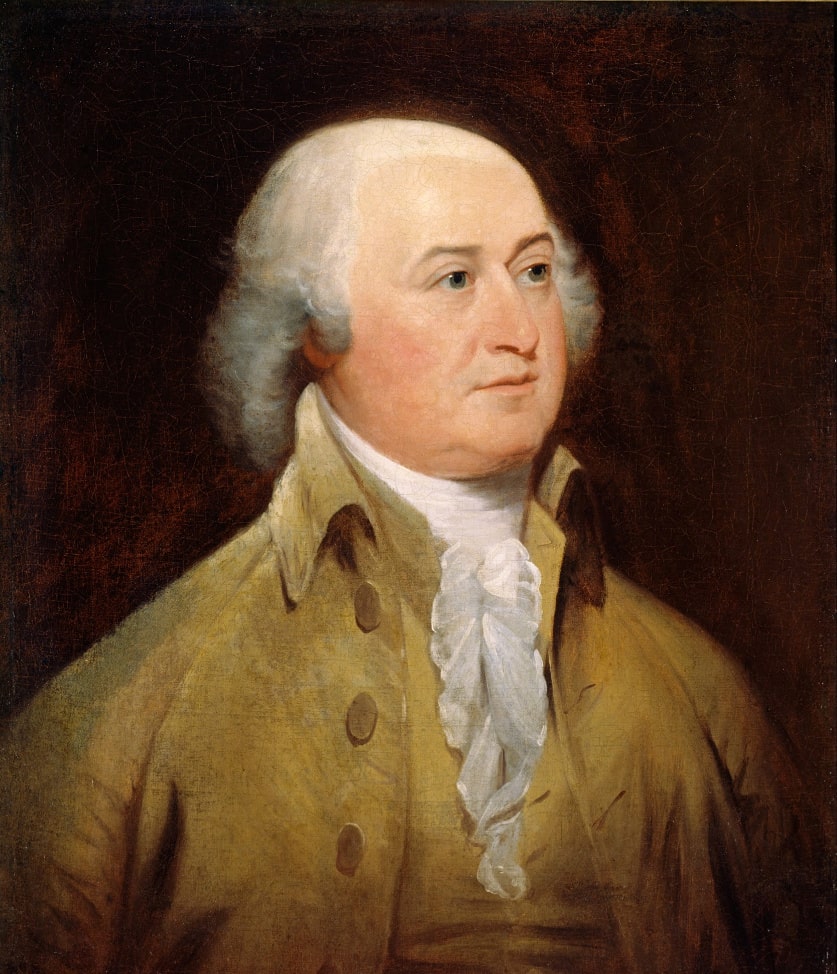

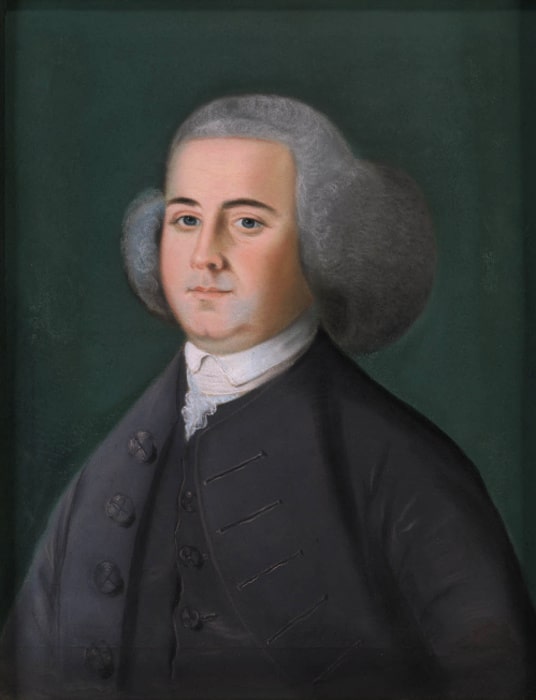

- Born: 30 October 1735 in the

north precinct

of Braintree, Massachusetts (now Quincy). - John Adams was the second President of the United States (1797–1801) and a leading advocate for American independence as a Founding Father.

- Before his presidency, he served as the first Vice President under George Washington and was a key diplomat in Europe during the Revolutionary War, helping to negotiate the Treaty of Paris, which ended the war.

- Adams played a pivotal role in the Continental Congress, where he championed the cause for independence and assisted in drafting the Declaration of Independence.

- He was a prominent lawyer and patriot in the years leading to the Revolution, known for his eloquent writings and speeches advocating colonial rights.

- As President, he navigated difficult foreign relations, particularly with France, and his administration saw the passage of the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts.

- Adams’ commitment to avoiding war with France, despite public and political pressure, is considered one of his most significant presidential achievements, though it cost him politically.

- Died: 4 July 1826 at his home, Peacefield, in Quincy, Massachusetts.

- Buried at Quincy, in a crypt at United First Parish Church.

Biography

He is vain, irritable and a bad calculator of the force and probable effect of the motives which govern men. This is all the ill which can possibly be said of him. He is as disinterested as the being which made him: he is profound in his views: and accurate in his judgment except where knowledge of the world is necessary to form a judgment. He is so amiable, that I pronounce you will love him if ever you become acquainted with him. He would be, as he was, a great man in Congress.

— Thomas Jefferson in a letter to James Madison, 1788

John Adams, second president of the United States, was born on 30 October 1735 in what is now the town of Quincy, Massachusetts. His father, a farmer also named John, was of the fourth generation in descent from Henry Adams, who emigrated from Devonshire, England, to Massachusetts about 1636; his mother was Susanna Boylston Adams.

Young Adams graduated from Harvard College in 1755, and for a time taught school at Worcester and studied law in the office of Rufus Putnam. In 1758 he was admitted to the bar. From an early age he developed the habit of writing descriptions of events and impressions of men. The earliest of these is his report of the argument of James Otis in the Superior Court of Massachusetts as to the constitutionality of writs of assistance. This was in 1761, and the argument inspired him with zeal for the cause of the American colonies. Years afterwards, when an old man, Adams undertook to write out at length his recollections of this scene, and it is instructive to compare the two accounts.

John Adams had none of the qualities of popular leadership which were so marked a characteristic of his second cousin, Samuel Adams; it was rather as a constitutional lawyer that he influenced the course of events. He was impetuous, intense and often vehement, unflinchingly courageous, devoted with his whole soul to the cause he had espoused; but his vanity, his pride of opinion, and his inborn contentiousness were serious handicaps to him in his political career. These qualities were particularly manifested at a later period — as, for example, during his term as president.

He first made his influence widely felt and became conspicuous as a leader of the Massachusetts Whigs during the discussions around the Stamp Act of 1765. In that year he drafted the instructions which were sent by the town of Braintree to its representatives in the Massachusetts legislature, and which served as a model for other towns in drawing up instructions to their representatives. In August 1765, he contributed, anonymously, four notable articles to the Boston Gazette (republished separately in London in 1768 as A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law). He argued that the opposition of the colonies to the Stamp Act was a part of the never-ending struggle between individualism and corporate authority. In December 1765, he delivered a speech before the governor and council in which he pronounced the Stamp Act invalid on the ground that Massachusetts, having no representation in Parliament, had not assented to it.

In 1768 he moved to Boston. Two years later, with that degree of moral courage which was one of his distinguishing characteristics (as it has been of his descendants), aided by Josiah Quincy, Jr., he defended the British soldiers who were arrested after the Boston Massacre,

and charged with causing the death of four inhabitants of Boston. The trial resulted in an acquittal of the officer who commanded the detachment and most of the soldiers; but two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. These claimed benefit of clergy and were branded in the hand and released. Adams’s upright and patriotic conduct in taking the unpopular side in this case met with its just reward in the following year. He was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives by a vote of 418 to 118.

Adams became a member of the Second Continental Congress from 1774 to 1778. His influence in Congress was enormous, and almost from the beginning he was impatient for a separation of the colonies from Great Britain. He served on many important committees, including the Board of War. In June 1775, with a view toward promoting the union of the colonies, he seconded the nomination of George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the army. On the 7 June 1776 he seconded the famous resolution, introduced by Richard Henry Lee, that q>these colonies are, and of a right ought to be, free and independent states, and no man championed these resolutions so eloquently and effectively before the Congress and they were adopted on 2 July. On the 8 June he was appointed to a committee with Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman to draft a Declaration of Independence. Adams insisted that Jefferson write the draft, but it was Adams who occupied the foremost place in the debate on its adoption.

In 1778, John Adams sailed for France to replace Silas Deane in the American commission there. But just as he embarked that commission concluded the desired Treaty of Alliance, and soon after his arrival he advised that the number of commissioners be reduced to one. His advice was followed; he returned home in time to be elected a member of the convention which framed the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, still the organic law of that commonwealth. With James Bowdoin and Samuel Adams, he formed a subcommittee which drew up the first draft of that instrument, and most of it probably came from John Adams’s pen. Before this work had been completed, he was again sent to Europe as minister plenipotentiary (27-Sep-1779) for negotiating a treaty of peace and a treaty of commerce with Great Britain.

Conditions were not then favorable for peace. Moreover, the French government did not approve of the choice, inasmuch as Adams was not sufficiently pliant and tractable and was from the first suspicious of finance minister comte de Vergennes.

Subsequently, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay and Henry Laurens were appointed to cooperate with Adams. Jefferson, however, did not cross the Atlantic, and Laurens took little part in the negotiations. This left the management of the business to the other three. Jay and Adams distrusted the good faith of the French government. Out-voting Franklin, they decided to break their instructions, which required them to make the most candid confidential communications on all subjects to the ministers of our generous ally, the king of France; to undertake nothing in the negotiations for peace or truce without their knowledge or concurrence; and ultimately to govern yourself by their advice and opinion

. Instead, they dealt directly with the British commissioners, without consulting the French ministers.

Throughout the negotiations Adams was especially determined that the right of the United States to the fisheries along the British-American coast should be recognized. Since current political conditions in Great Britain made the conclusion of peace almost a necessity with the British ministry, eventually the American negotiators were able to secure a peculiarly favorable treaty. This preliminary treaty was signed on the 30 November 1782.

Before these negotiations began, Adams spent time in the Netherlands. In July 1780 he had been authorized to execute the duties previously assigned to Henry Laurens, and at the Hague was eminently successful, securing recognition of the United States as an independent government (19 April 1782); negotiating a loan; and negotiating a Treaty of Amity and Commerce. (October 1782). These were the first of such treaties between the United States and foreign powers after that of the February 1778 Treaty of Amity and Commerce with France.

In 1785 John Adams was appointed the first — in a long line of able and distinguished American ministers — to the Court of St. James’s. When he was presented to his former sovereign, King George III intimated that he was aware of Mr. Adams’s lack of confidence in the French government. To which Adams replied I must avow to your Majesty that I have no attachment but to my own country.

King George smiled ever so slightly and responded, An honest man will never have any other.

While in London Adams published A Defense of the Constitution of Government of the United States (1787). In this work he ably combated the views of Turgot and other European writers as to the viciousness of the framework of the state governments. Unfortunately, in so doing, he used phrases seemingly positive of aristocracy — which offended many of his countrymen — as in the sentence in which he suggested that the rich, the well-born and the able

should be set apart from other men in a senate.

Partly for this reason, while Washington had the vote of every elector in the first presidential election of 1789, Adams received only thirty-four out of sixty-nine. As this was the second largest number he was declared Vice President. Thus he began his eight years in that office with a sense of grievance and of suspicion of many of the leading men.

Differences of opinion regarding the policies to be pursued by the new government gradually led to the formation of two well-defined political groups —the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans — and Adams became recognized as one of the leaders of the former, second only to Alexander Hamilton. In 1796, on the refusal of Washington to accept another election, Adams was chosen President, defeating Thomas Jefferson; though Alexander Hamilton and other Federalists had asked that an equal vote should be cast for Adams and Thomas Pinckney, the other Federalist in the contest, partly in order that Jefferson, who was elected Vice President, might be excluded altogether, and partly, it seems, in the hope that Pinckney should in fact receive more votes than Adams, and thus, in accordance with the system then obtaining, be elected President — though he was intended for the second place on the Federalist ticket.

Adams’s four years as President (1797—1801) were marked by a succession of intrigues which embittered him the remainder of his life. They were marked also by events, such as the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, which brought discredit to the Federalist party. Moreover, factional strife broke out within the party itself; Adams and Hamilton became alienated, and members of Adams’s own cabinet virtually looked to Hamilton rather than to the President as their political chief.

The United States was, at this time, drawn into the vortex of European complications, and Adams, instead of taking advantage of the militant spirit which was aroused, patriotically devoted himself to securing peace with France — much against the wishes of Hamilton and of Hamilton’s adherents in the cabinet. In 1800 Adams was again the Federalist candidate for the presidency, but the distrust of him in his own party, the popular disapproval of the Alien and Sedition Acts, and the popularity of his opponent, Thomas Jefferson, all combined to cause his defeat. He then retired into private life.

In 1764 Adams had married Abigail Smith (1744—1818), the daughter of a Congregational minister in Weymouth, Massachusetts. She was a woman of much ability, and her letters, written in an excellent English style, are of great value to students of the period in which she lived. John Quincy Adams, who became the sixth president of the United States (1825—29), was their eldest son.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1826, John Adams died at his farm in Quincy. In an astonishing historical coincidence, Thomas Jefferson died on the same day.