Contents

Contents

The economy of the Southern Colonies was primarily centered on the region’s plantation farms, with crops such as tobacco, indigo, and rice being key exports for the region.

Plantations and farming

Due to its warm climate, long growing season, and fertile soils, the Southern Colonies in America were the perfect place for large-scale farming in the New World.

This began in the early 1600s, when Virginia discovered that tobacco was the perfect cash crop to ensure the initial survival of the colony.

From this point, plantations sprang up around the Southern Colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries, with Maryland becoming the second-biggest tobacco producer.

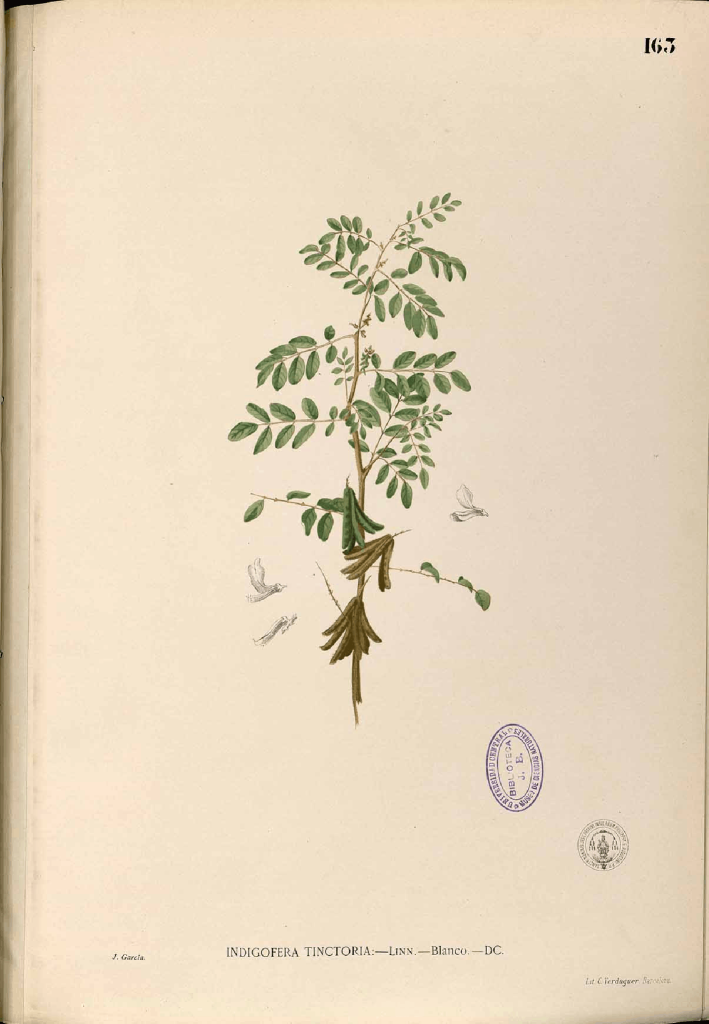

Tobacco was the biggest export of the region during the colonial period, but indigo (used to make dye) plantations grew in number over time, especially in South Carolina, and especially from the 1740s onwards.

Large amounts of rice were grown along the coast in swampy, lowland areas, especially in the lower south, and the region eventually began to grow wheat and raise cattle as well.

Cash crops were predominantly exported to Europe or other British overseas territories, and the profits were used to finance further land purchases or seizures from Native American tribes.

By 1775, tobacco made up 75% of the total export output of Virginia and Maryland, and the majority of these goods were shipped to England.

Labor and slaves

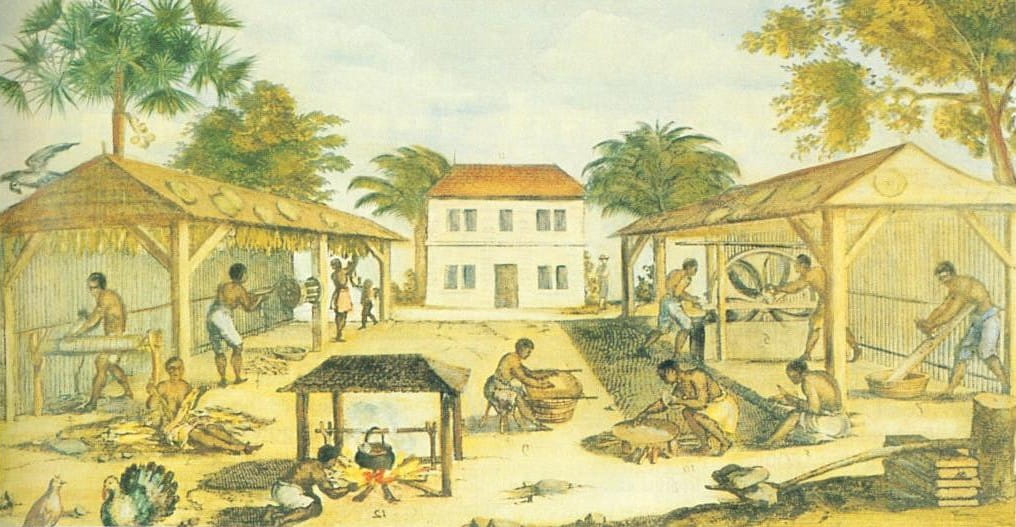

The Southern Colonies’ plantations were extremely labor-intensive. They required large numbers of people working continuously to sow seeds, control irrigation, and harvest and process crops.

In the colonies’ early history, these roles were performed by indentured servants, who agreed to work for free or little pay for a set period of time in return for their transportation to the New World.

However, the need for labor increased massively over time, so in the mid-to-late 1600s, the Southern Colonies began importing large numbers of slaves from Africa to work on the plantations, and the practice was legally formalized in most of the region.

Virginia was the first of the Thirteen Colonies to import slaves, beginning in 1619, and has a history of enslaving Native Americans from the very start of the colonial era.

In Georgia, slavery was banned in 1735, three years after the colony received its charter. However, this restriction was lifted in 1751, opening the door to slave imports.

Legally, slaves were often required to work for life, and their children generally inherited their mothers’ status as owned by a specific person or family. They were treated as property, bought and sold at markets, and those on the plantations were made to work from sunrise to sunset.

Demand for slaves continued to rise sharply in the 1700s, and by 1770, in each of the Southern Colonies, approximately 30 to 60 percent of the population was black.

Wealth inequality

The Southern Colonies had a particularly high level of wealth inequality compared to other parts of British North America.

Plantations were often controlled by wealthy landowners that owned multiple farms, each with its own slave labor force.

In certain colonies, such as South Carolina, the export economy was dominated by these wealthy landowners.

Elite families would often live by the coast for its easy access to trade networks and transport, and because these regions had the best farmland in the colonies.

On the other hand, less wealthy European migrants to the region would often settle in the backcountry, along the Appalachian Range or Piedmont Plateau. There, they would set up small-scale subsistence farms, growing crops such as wheat and occasionally raising animals for the purposes of sustaining themselves, rather than producing goods for sale or trade.

Imported manufactured goods

While the Southern Colonies exported huge volumes of cash crops such as tobacco, their economies heavily relied on imports of finished products.

This included tools, farming equipment, clothes, ceramics, and luxury goods for elite plantation owners.

These goods needed to be imported because manufacturing capabilities were relatively limited in the Southern Colonies, due to how focused the region was on its agricultural output.

This way of doing things was also beneficial for British colonial powers, because it supported domestic manufacturing in England. The Southern Colonies were encouraged to focus on producing agricultural outputs for the British Empire.

Export restrictions

While the Southern Colonies were major exporters, they were not allowed to practice free trade.

Legally, exported goods were largely required to be shipped to England or English overseas colonies, rather than directly to Europe, under the Navigation Acts first put in place in 1651.

The economic system that the British Empire established in the Southern Colonies is sometimes known as the triangular trade.

- The Southern Colonies (and the New England and Middle Colonies) imported slaves from Africa.

- These slaves were used to produce cash crops such as tobacco, which were exported to Europe.

- Europe would export finished products such as tools, weapons, alcohol, and clothing to Africa, helping British exporters. Slave traders often exchanged African people they had in their possession for these manufactured goods.

In saying this, the Navigation Acts were not always strictly enforced, due to British salutary neglect through to the mid-1700s.

Other small-scale exports

- In Virginia and Maryland, small amounts of bog iron were harvested from swamps and lowlands before being cleaned, dried, and smelted locally. The Southern Colonies had large amounts of mineral and precious metal deposits, but these were mostly left unexploited until after the American Revolution.

- The South had millions of acres of pristine forests, making lumber a small but important economic asset for the Southern Colonies. Wood was used for fuel, but timber was also exported or used locally in shipbuilding, and to create barrels, plantation structures, and houses.

- In the backcountry, animal pelts such as deerskins were acquired from Native American tribes before being exported to Europe for use in luxury fashion, and to make leather products. Rather than being sold for cash, the native peoples were given goods such as gunpowder, axes, foodstuffs, and clothes in exchange for the furs they hunted.

- Some areas, especially North Carolina, specialized in the production of products made from pine trees, which were essential for the naval industry in particular. This included tar (a black, sticky substance used for waterproofing), pitch (similar to tar but thicker and more concentrated, used as a sealant), and turpentine (distilled pine sap, used as a solvent, for cleaning, and as fuel).

Transport and waterways

The economy of the Southern Colonies relied heavily on the region’s system of rivers and waterways.

Crops and other exports were loaded onto ships and carried along rivers, towards the coast. Often, plantations were built close to these waterways, to allow for easier transportation.

Heading east, cargo was often transferred from smaller to larger ships after reaching the fall line; where the Piedmont Plateau reaches the coastal lowlands of the Southern Colonies.

This area was usually marked by a sharp drop-off in the river, making it a place where goods needed to be transferred between vessels. These areas often became trading hubs because of the amount of economic activity that occurred nearby.

The Southern Colonies’ coast is heavily tidal in places, which often made it easier for large ships to sail far inland, with the correct timing. Though, in other areas, shallow waters and constantly-shifting sandbanks made navigation difficult.

After leaving the inland waterways, goods were taken to ports such as Charleston, Baltimore, and Savannah, and prepared for export.