Contents

Contents

The Southern Colonies had large swathes of flat, fertile land, which along with its warm climate and system of waterways, made the region perfect for plantation-based farming.

Terrain

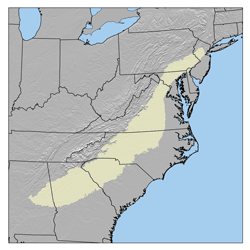

The terrain of the Southern Colonies had a range of different features in different areas, which can be thought of in terms of bands running parallel to the coast.

- Along the coast, there was a large coastal plain, with low, flat lands, swamps, floodplains, and sandy soils. This was where most plantations were located, and was also where the wealthiest citizens usually lived.

- Moving west, the terrain became steeper on the Piedmont Plateau, and the soil had a higher clay content, meaning it drained better, and made it more suitable for traditional farming, such as growing wheat and barley.

- Further inland were the Appalachian Mountains, with even steeper terrain in areas, and landscapes criss-crossed with rivers and valleys.

The Appalachian and Piedmont region of the Southern Colonies was also known as the Backcountry, and due to the uneven terrain, navigating this area often proved difficult during the colonies’ early history.

Climate

In comparison to the Middle Colonies and especially New England, the Southern Colonies had a much warmer climate, which made for a longer growing season.

While farmers in other parts of British North America might be able to grow crops for three to six months a year, depending on how far north they were, the growing season lasted for seven to nine months in the Southern Colonies.

South Carolina and Georgia had particularly mild winters, while the chill could be felt slightly in the colder months in Maryland and Virginia.

The Southern Colonies also had a particularly humid climate, and were frequently hit by large storms and hurricanes.

Forests and lumber

The southern area of the present-day United States is estimated to have had 350 million acres of forests in the early 1600s, much of which was located in the Southern Colonies.

As a result, another key economic asset of the region was its forests, which were spread throughout the coastal region and the Piedmont Plateau.

Timber was cut down and used to make houses, barns, or to build or repair ships. Forests were also cleared to make way for plantations and cattle grazing.

As the Southern Colonies became increasingly deforested throughout the 1700s, settlers moved inland to find new sources of timber, including in the Appalachian range.

Waterways

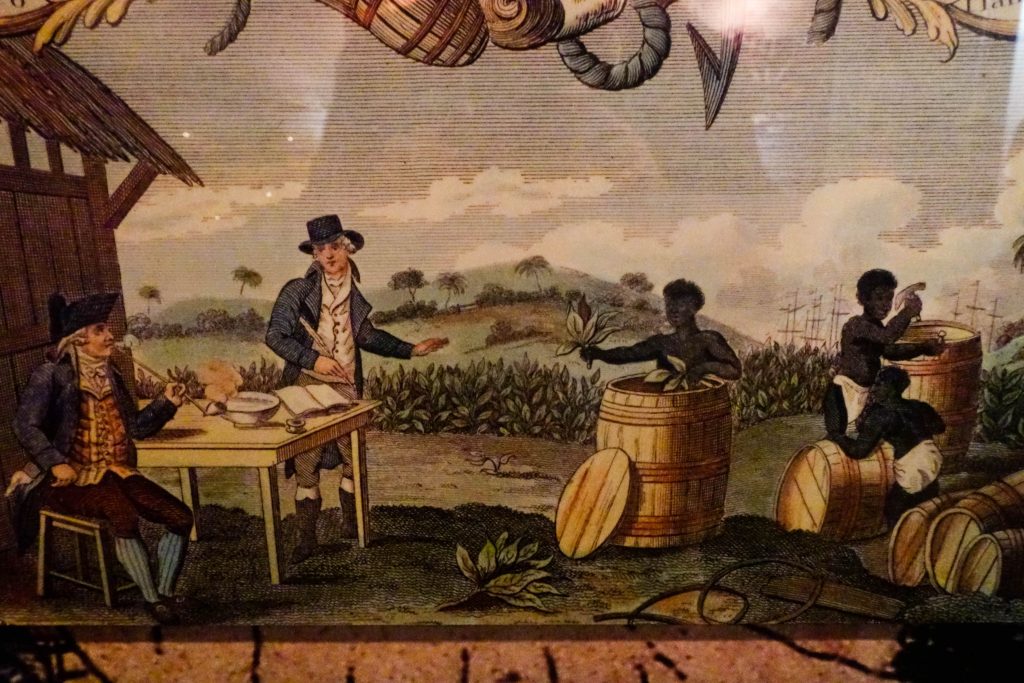

The Southern Colonies’ plantation-based economy relied heavily on the region’s system of rivers, tributaries, and estuaries to facilitate trade.

One of the region’s biggest assets was its system of large, easy-to-navigate rivers. In the north, major rivers flowed into Chesapeake Bay, allowing for easy access to the ocean.

Plantations were often built on riverbanks to allow for the easy transport of goods, and many settlers lived on these waterways as well, as they made transport and trade significantly easier.

These rivers flowed from higher lands on the Piedmont Plateau out to the coast, and were used to transport goods such as tobacco, rice, timber, and indigo between towns, to different colonies, and internationally.

The point where the rivers dropped from the Piedmont onto the coastal plain was called the “fall line,” and was often marked by small waterfalls or rapids. It was here that many settlements were created, as this was a natural transfer point from smaller to bigger boats, and these fall line towns often became inland trading hubs.

The coast

The coast of the Southern Colonies was very sheltered in a lot of places, making it easy for ships to access areas such as Chesapeake Bay.

North Carolina had an extensive chain of barrier islands, which led to the formation of sheltered inland waters, known as sounds.

However, these coastal waters were extremely tidal, which could make navigating the area tricky outside of the major bays, especially for larger boats. Sandbars and shoals could change extensively over time, especially after storms, and the sounds were often very shallow.

Along the North Carolinian coast, the sounds formed by the colony’s barrier islands were a perfect place for fishing, and floodplains in Georgia and the Carolinas were used to cultivate large quantities of rice.

The coastal areas were at times difficult to settle due to the risk of flooding, the huge areas of swamp and marshland in these regions, and the large numbers of mosquitoes that were prevalent in the area.

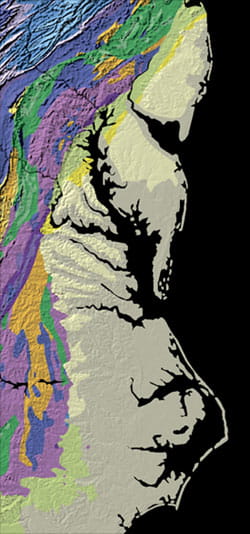

Geology and mining

There were significant precious metal and mineral deposits in the Southern Colonies, though mining was not a large contributor to the region’s economy, and most of these resources would not be exploited until after the colonial period.

The Chesapeake’s coastal soils were made up of unconsolidated sediments such as sand, gravel, silt, and clay, which were the perfect conditions for the formation of iron. As a result, beginning in the early 1600s, small amounts of bog iron were mined in low, wet parts of Virginia and Maryland.

These resources were extracted in lumps from marsh and swamp beds, before being cleaned, dried, and transported to a blast furnace for smelting.

The Piedmont area was made up of crystalline rocks, and it was in this region that the first gold was discovered in the United States at Reed Gold Mine, North Carolina, in 1799.