Contents

Contents

The Southern Colonies in British North America were predominantly Anglican, but a wide variety of different religious sects coexisted in the region, including Presbyterians, Quakers, Baptists, and Catholics.

Early years

The majority of the Southern Colonies were created with the Anglican Church of England as the established religion of the state.

What this actually meant depended on the colony, and varied over time. In some cases, there were mandatory church taxes that had to be paid, even by non-Anglicans, and dissenters (especially Catholics and Jews) were sometimes persecuted for their beliefs, and often prohibited from holding public office.

However, the majority of the time in the south, other non-Anglican Protestant sects were allowed to practice their beliefs freely, without having to pay mandatory parish taxes to other churches.

Virginia was the first of the Thirteen Colonies, and after settlement, the colonists quickly set about establishing the Church of England as the official religion.

The territories that would later become Georgia and the Carolinas were initially governed by a charter given to eight Lords Proprietors by King Charles II in 1663.

Like the king, these proprietors were Anglicans, and they also set about establishing the Church of England as the official religion of the colony. When Georgia split off in 1732, the charter provided for religious freedom for all Protestants, while explicitly excluding Catholics.

Maryland was the exception to the rest of the Southern Colonies in that it was tolerant of Catholics, at least to begin with.

The colony was founded in 1634, and it was partly intended as a safe haven for Catholics in the New World, meaning it had a much greater Catholic population than any of the other Thirteen Colonies.

Religion in practice

Despite the Southern Colonies having official religions, in reality the region was very diverse, especially compared to the New England colonies.

In the south, settlements were often located far apart, meaning it was difficult to attend church. These logistical challenges led to clergy shortages, and caused difficulty in establishing Anglican churches in the region.

In many colonies, Virginia especially, the Anglican Church was designed to operate a parish and vestry system, meaning it would run local governance in each individual settlement. However, because the parish areas were so big, and there was a lack of clergymen to cover the ground, the system often did not work effectively in the Southern Colonies.

As a result, religion was disorganized, with sermons delivered by laypeople in small settlements, and a lack of enforcement of Anglican rules led to a significant increase in religious diversity in the second half of the 1600s.

In the Carolinas in particular, the Lords Proprietors permitted wide-ranging religious freedom to encourage migration to the region. As a result, the colony became home to a large number of Quakers, especially during its early years.

German Lutherans and members of the Reformed Church also moved to the Carolinas, along with Moravians, and French Huguenots (Calvinist Protestants) established themselves in the southern half of the province.

Once Georgia established itself in the 1730s, the new colony attracted a wide range of different types of migrants, including British Anglicans, German-speaking Protestants, Jews, and Puritans.

In general, coastal regions of the Southern Colonies were home to plantations and the Anglican elite, while inland backcountry areas drew in migrants who were predominantly Presbyterian and Baptist.

Anglican, Presbyterian, and Moravian missionaries attempted to spread their religions to native populations in the Southern Colonies, with varying degrees of success. As conflict between settlers and indigenous populations increased in the 1700s, missionary work became more difficult.

Religious conflict

The religious diversity of the Southern Colonies led to instances of conflict between different sects around the early-to-mid 1700s.

In the Carolinas, Quakers and Anglicans fought for control of the colony. When Anglicans were in power, they sought to enforce mandatory parish taxes to fund the Church of England, and excluded Quakers from government by forcing them to swear an oath – rather than affirming their allegiance – which goes against Quaker moral codes.

In Maryland, Protestants rose up against the Catholic-led government in 1689, overthrowing the Calvert family, and effectively ending tolerance for Catholics in the colony for the remainder of its history.

This mirrored England’s 1688 Glorious Revolution, where Catholic King James II was deposed in favor of Protestant monarchs William and Mary.

In Georgia, there were tensions over the first Jewish settlement in Savannah, and Moravians, as pacifists, elected to leave the colony in 1740 rather than fight against the Spanish to the south.

Later on, after the First Great Awakening, Baptist preachers were arrested in Virginia in the 1760s, as the Anglican Church cracked down on evangelical Protestant sects.

The First Great Awakening

In the 1730s and 1740s, there was a period of religious revival throughout British North America, known as the First Great Awakening. This movement significantly affected the religious makeup of the Southern Colonies.

During this period, evangelical preachers traveled throughout the colonies, encouraging a renewed devotion to God, promoting individualism, and challenging the authority of the established churches.

The Awakening led to a rise in popularity of Baptist sects, causing a substantial increase in their numbers during the 1750s and 1760s. This growth was concentrated in certain areas, such as backcountry North Carolina.

The movement also widened the gap between the formal establishment and popular religious life, again moving the population away from the Church of England.

Religious diversity further increased during this time, as Protestant sects divided based on their level of evangelism. On the one side there were conservative groups that continued to hold traditional-style sermons, and on the other there were more progressive “New Side” sects, which practiced more energetic, evangelical church meetings.

Despite this though, Anglicanism remained the most popular religion in the Southern Colonies up until the Revolutionary War.

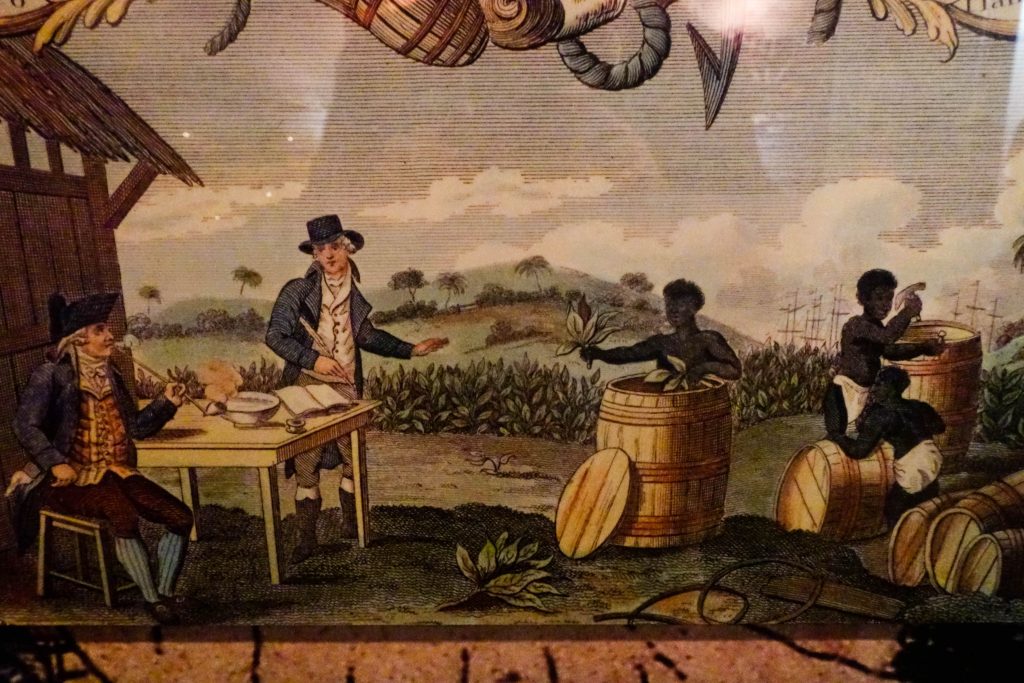

Slavery and religion

The Southern Colonies had the most slaves of any of Britain’s North American territories. By the end of the Revolutionary War, roughly half of the population of Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina was black.

Slaves’ experiences with religion in the Southern Colonies were mixed.

- Many slaveowners specifically avoided exposing their slaves to religion, for fear it could lead to a perceived spiritual equality between enslaved and free men, potentially leading to an uprising.

- Some preached specific aspects of Christianity to their slaves, especially those that they believed would foster a sense of obedience.

Whether exposed to Christianity or not, many of the first African Americans continued religious practices from their homeland, such as invoking ancestral spirits, using magic, and performing healing ceremonies based on herbs and other natural remedies.

After the Great Awakening, certain more radical Protestant sects began preaching openly to African American slaves, though some slaveowners opposed this, for fear it would incite class-based rhetoric, especially given how New Lights often emphasized topics such as individuality, liberty, and justice in their sermons.

Pastor Samuel Davies is said to have baptized more than 100 enslaved people in Virginia by 1755, though he was a slaveowner himself.