Contents

Contents

Chapters

- Chapter 1: The Opening of Hostilities, 1775

- Chapter 2: Naval Administration and Organization

- Chapter 3: Washington’s Fleet, 1775 and 1776

- Chapter 4: The New Providence Expedition, 1776

- Chapter 5: Other Events in the Sea in 1776

- Chapter 6: Lake Champlain, 1776

- Chapter 7: Naval Operations in 1777

- Chapter 8: Foreign Relations, 1777

- Chapter 9: Naval Operations in 1778

- Chapter 10: European Waters in 1778

- Chapter 11: Naval Operations in 1779

- Chapter 12: The Penobscot Expedition, 1779

- Chapter 13: A Cruise Around the British Isles, 1779

- Chapter 14: Naval Operations in 1780

- Chapter 15: European Waters in 1780

- Chapter 16: Naval Operations in 1781

- Chapter 17: The End of the War, 1782 and 1783

- Chapter 18: Naval Prisoners

- Chapter 19: Naval Conditions of the Revolution

- Appendix

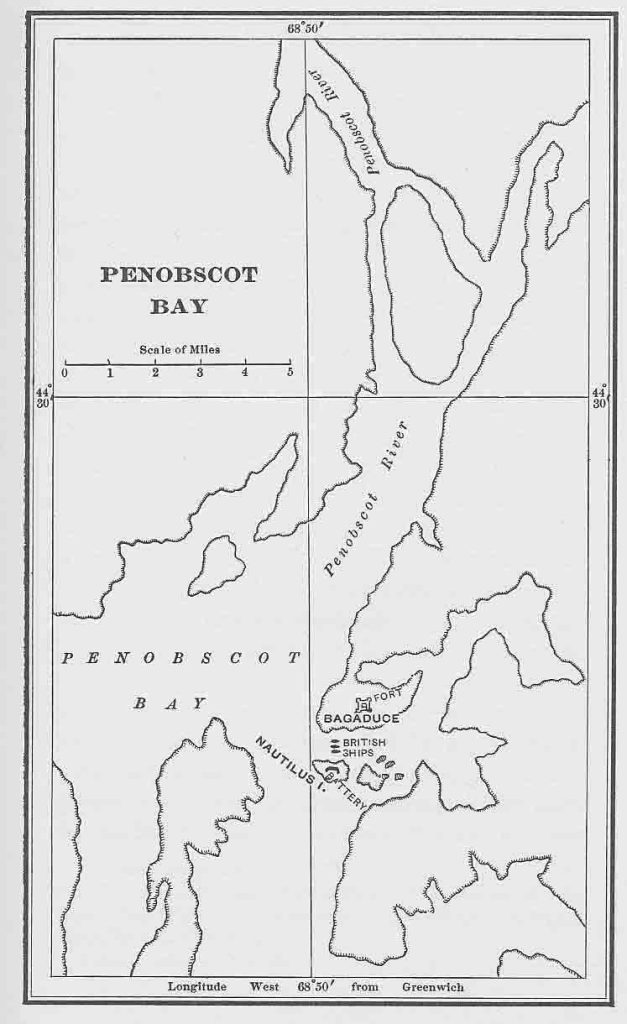

For the third time within a century a military expedition of importance and magnitude, considering the resources of the community, was fitted out at Boston for service against a foreign enemy. In 1690 the forces of the colony under Phips attempted the conquest of Quebec; in 1745, led by Pepperell, they captured Louisburg (Expeditions against Acadia under. Colonels Church and March in 1704 and 1707 might also be mentioned.); and now in 1779 the citizens of Massachusetts assumed, practically alone, the burden of a new enterprise, an effort to repel an invasion of their territory. About the middle of June eight hundred or more British troops from Halifax, convoyed by three sloops of war under the command of Captain Mowatt, entered Penobscot Bay and took possession of the peninsula of Maja-bagaduce or Bagaduce, now called Castine. The object of this move was the establishment of a new province, furnishing a home for many of the numerous loyalists under British protection in Nova Scotia and elsewhere and at the same time serving as a bulwark for British possessions farther east and as an advanced military post convenient for operating against New England (Hist. Man. Com., Amer. MSS. in Royal Inst., i, 284 (Germain to Clinton, September 2, 1778), 381 (Clinton to General McLean, February 11, 1779), 393, 415, 436, 440 (correspondence relating to proposed seizure of Penobscot), 452-462 (letters of McLean, Mowatt, etc., from Penobscot, June, 1779)

When the news of the British occupation reached Boston the General Court was in session, and it was soon determined to drive out the enemy, if possible, before he had had time to strengthen his position. Preparations were made with energy and a military and naval force was soon organized, although the full number of militia called for could not be obtained. Application was made to the Continental Congress for the services of three national vessels at that time in Boston Harbor and they accompanied the expedition. New Hampshire contributed one vessel. All the rest of the force was made up and the expense borne by Massachusetts (The principal original authorities for the Penobscot Expedition are: Mass. Archives and Rev. Rolls; General Lovell’s Journal, published by Weymouth Hist. Soc., 1881; Journal of the Privateer Ship Hunter, printed in Hist. Mag., February, 1864; various papers in Wheeler’s History of Castine; letters published by the State of Massachusetts in Proceedings of the General Assembly relating to the Penobscot Expedition, 1780; contemporary newspapers, e.g., Boston Gazette, August 9, September 27, December 27, 1779, March 18, 25, April 1, 8, 15, 1782; Boston Post, July 10, 1779; Continental Journal, January 6, 1780; London Chronicle, September 25, 28, 1779; Brit. Adm. Records, Captains’ Letters and Cptains’ Logs; Almon, viii, 352-359. See also Town, 102-115.)

The fleet organized for this enterprise consisted of nineteen armed vessels and twenty or more transports. The Continental vessels were the frigate Warren, 32, Commodore Saltonstall, the brig Diligent, 14, Captain Brown, and the sloop Providence, 12, Captain Hacker. The state navy furnished the brigs Hazard, Active and Tyrannicide of fourteen guns each, commanded by Captains Williams, Hallet, and Cathcart. The Diligent and the Active had recently been taken from the British. In addition to these six vessels, twelve privateers were taken into the service of the state, the owners being guaranteed against loss. Four of these privateers carried twenty guns each and four others eighteen guns, while of the remaining four there was one sixteen, two fourteens, and one eight. Eight of the privateers were ship-rigged. One vessel was furnished by New Hampshire, the twenty-gun ship Hampden, a privateer temporarily taken into the service of that state. The fleet carried over two hundred guns, a large proportion of them probably light ones, and more than two thousand men; Saltonstall was in command. The military force on board the transports it had been intended to recruit to the number of fifteen hundred men, but owing to hurried preparations, less than a thousand apparently embarked on the fleet; and they, according to the testimony of the officers, were a very inferior set of men, even for militia. These troops were under the orders of General Solomon Lovell, with General Peleg Wadsworth second in command and Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Revere in charge of the artillery (Court Records, June 24, 1779.)

On June 25, the General Court made provision for “Nine tons of Flour or Bread, Nine Tons of Rice, Eighteen Tons of Salt Beef, six hundred Gallons of Rum, six hundred Gallons of Molasses, Five hundred stand of Fire Arms.” (Court Records.) On July 13, Commodore Saltonstall was instructed by the Board of War “to take every measure & use your utmost Endeavours, to Captivate, Kill or destroy the Enemies whole Force both by Sea & Land, & the more effectually to answer that purpose, you are to Consult measures & preserve the greatest harmony with the Commander of the Land Forces, that the navy & army may Cooperate & assist each other.” (Mass. Archives, cxlv, 39.) It would have been well if this injunction had been strictly heeded. Lack of cooperation between army and navy, a cause that has brought disaster upon many a joint expedition, was to have its baleful effect on this. Another source of weakness was Saltonstall’s incompetency. It was also unfortunate that the necessity for prompt action, with a view to forestalling reinforcements of the enemy, made it impracticable to enlist the number of men that had been considered essential for the success of the enterprise. Moreover, for the important and difficult work in prospect, that of assaulting fortifications, a fair proportion at least of regular troops should have been incorporated with the force. The fleet sailed from Boston July 19. They proceeded first to Townsend (Boothbay Harbor), the appointed rendezvous, where it had been expected that the full complement of men would be made up, but the general was disappointed. Unwilling to delay, he set sail again on the 24th (Weymouth Hist. Soc., 1881, Sketch of Lovell, ch. vii.)

Information of the departure of this expedition reached English ears no earlier perhaps than might have been expected. Commodore Collier wrote from New York July 28: “I received this morning certain intelligence that an armament sailed from Boston on the 21st instant to attack his Majesty’s new settlement in Penobscot River . . . I intend putting to sea at daylight tomorrow,” (Almon, viii, 356.) in pursuit. While the sloop Providence was fitting out at Boston, Lieutenant Trevett, who had long served on board that vessel, decided to remain at home and attend to his private business, saying that he had “no particular inclination to go to Penobscot, for I think the British will get information either at New York or Newport before our fleet can get ready to sail and if they do, I know that three or four large British ships can block them in and that will be the last of all our shipping.” (R. I. Hist. Mag., October, 1886.)

The fleet arrived in Penobscot Bay July 25, in the afternoon. There were three British sloops of war in the harbor, the North, of twenty, and the Albany and Nautilus of eighteen guns each. Nine of the American ships, in three divisions, stood towards these vessels, hove to and engaged them. There was a brisk fire for two hours without much effect. In a report to the President of the Massachusetts Council, dated three days later, General Lovell says: “I the same evening attempted to make a lodgment on Majorbagaduce, but the wind springing up very strong, I was obliged to desist, lest the first division might suffer before they could be supported by the second. On the 26th I took possession with the marines, supported by General Wadsworth’s division, of an island in the harbour, beat them off, took 4 pieces of artillery and some ammunition.” (Boston Gazette, August 9, 1779.) The landing was made on Nautilus Island, also known as Banks Island. Captain Cathcart of the Tyrannicide says of this affair that “on the 26th July a Council was held on board the Warren, where it was agreed that each Ship or Armed Vessel should furnish such a Number of Marines to take possession of Banks’s Island on the South side of the Entrance of Bagaduce River under cover of the Sloop Providence, Brig Pallas & Defence.” (Rev. Rolls, xxxix, 113.) An officer on board the ordnance brig, presumably Revere, gives another account of this episode, dated July 29, saying that “the marines attacked an island where the enemy had a battery of 2 guns; they were commanded by Captain Welsh of the Warren. I sent one field piece to support them; they landed under cover of three vessels. The enemy quitted it with precipitation, left their colours flying and four pieces of cannon, two of them not mounted. We immediately built a battery there and mounted two 18 and one 12 pounder. This island is directly opposite to the enemy and commands the mouth of the harbour.” (Boston Gazette, August 9, 1779.) This battery forced the British ships to shift their anchorage further up the harbor (Hist. Mag., February, 1864; Wheeler, 293, Journal of John Calef; Brit. Adm. Rec., Captains’ Logs, Nos. 23 and 630, logs of the Albany and Nautilus.)

On the 27th there seems to have been lack of harmony between the military and naval commanders and a misunderstanding about the landing of the marines in an attack on the peninsula of Bagaduce. The importance of prompt and energetic action was appreciated by some of the subordinate naval officers, who presented to the commodore on that day a petition in which they “Would Represent to your Honour that the most spedy Exertions should be used to accomplish the design we came upon. We think Delays in the present Case are extremely dangerous, as our Enemies are daily Fortifying and Strengthening themselves & are stimulated so to do, being in daily Expectation of Reinforcement”; they did not wish to advise or censure, but only “to express our desire of improving the present Opportunity to go Immediately into the Harbour & Attack the Enemy’s Ships.” (Mass. Archives, cxlv, 50.) It was the opinion of these officers that the capture of the British post at Bagaduce would be greatly facilitated and hastened by removing the ships which supported it. By evening arrangements had been made for landing the marines on the peninsula. At three the next morning the commodore ordered Cathcart “to begin to fire into the Woods with an Intent to scower them of the Enemy, which was Immediately obey’d.” (Rev. Rolls, xxxix, 113.)

Early on July 28 the attack was made on Bagaduce. The Warren engaged the British ships at long range and they moved still farther up the harbor, to escape the fire of the battery on Nautilus Island. Lovell says: “This morning I have made my landing good on the S. W. head of a Peninsula which is 100 feet high and almost perpendicular, very thickly covered with bush and trees. The men ascended the precipice with alacrity and after a very smart conflict we put them to the rout. They left in the woods a number killed and wounded and we took a few prisoners; our loss is about 30 killed and wounded. We are within 100 rods of the enemies main fort, on a commanding piece of ground. I hope soon to have the satisfaction of informing you of the capture of the whole army.” (Boston Gazette, August 9, 1779.) “We landed in three divisions,” says Colonel Revere, “the marines on the right, Col. Mitchell on the left, and Col. Mc. Cobb, the volunteers and my corps in the centre. The land being so mountainous and full of wood that our cannon could not play, I landed with my small arms, the whole force under cover of two ships and three brigs, who drew near the shore and kept up a constant fire into the woods till we began to land. The enemy’s greatest strength lay upon our right, where the marines landed; they had three hundred in the woods. As soon as the right landed they were briskly attacked. The enemy had the most advantageous place I ever saw; it is a bank above three hundred feet high and so steep that no person can get up it but by pushing himself up by bushes and trees, with which it is covered. In less than 20 minutes the enemy gave way and we pursued them. They left twelve dead on the spot, 8 wounded and about 10 prisoners. We lost about 35 killed and wounded. We took possession of a height near their fort and are now building a battery to play upon them. I expect to put two 18 pounders, one 12, two 4, and a howitz on shore this day. I am in hopes that if the ships go into the harbour today [July 29], as it is said they will, and take their ships, we shall have an easy conquest. In the afternoon we took another battery of three 6 pounders, upon which they abandoned it and went into their fortress.” (Boston Gazette, August 9, 1779.) Another officer puts the American loss at ten killed and twenty wounded (lbid.; Wheeler, 295 ; Hist. Mag., February, 1864.)

On the 29th, according to Cathcart, it was agreed that the ships should go in and attack the enemy’s squadron, but the next day, at a council of war on board the Warren, Saltonstall said there was no sufficient reason for the ships’ going in. At this time, July 30, a galley arrived from Boston and three days later was sent back with Lovell’s dispatches. Frequent councils were held on the Warren, but with little result. The marines gave some assistance to the army, but with this exception the navy was of little service. The commodore, upheld by the privateer captains, remained inactive day after day, apparently incapable of coming to a decision. He seems to have feared the exposure of his ships to the fire of the fort while attacking the enemy’s ships and to have insisted that the fort should be captured first; whereas Lovell’s force was insufficient to justify an assault on the stronghold supported as it was by the British ships. Meanwhile the army erected batteries at different points for the reduction of the fort, if possible, and for the annoyance of the little squadron, which it would seem might easily have been captured, destroyed, or driven away at the outset of operations by the vastly superior American fleet. August 6, Lovell notes in his journal: “I wrote a Letter to the Commodore desiring an answer whether he wou’d or whether he wou’d not go in with his Ships & destroy the Shipping of the Enemy, which consist only of three Sloops of war, when he returned for answer, if I wou’d storm the fort he wou’d go in with his Ships, upon which I called a Council, the result of which was that in our present situation it was impracticable, with any prospect of Success.” A simultaneous attack by army and navy might have succeeded. Lovell. himself, perhaps, was moved by excess of prudence; but he lacked confidence in his men.

Notwithstanding the steadiness with which the militia, with the help of the marines, carried the precipitous heights of Bagaduce on July 28, part of their subsequent behavior convinced the general of their unreliable character. He continued to urge more naval activity and wrote to the commodore August 11: “The destruction of the Enemy’s ships must be effected at any rate, although it might cost us half our own.” (Wheeler, 310; Lovells Journal; Rev. Rolls, xxxix, , 113; Hist. Mag., February, 1864.)

Meanwhile the commodore had had a somewhat ridiculous adventure August 7, described in Lovell’s journal: “A Boat from the Hazard with Comr Saltonstall, Capts Waters, Williams, Salter, Holmes & Burke were a reconnoitering up a Cove nigh the Enemy’s Ships; on their discovering them they immediately sent 8 Boats armed, to hem them in. They so far succeeded that they made a prize of the Boat, but the Gentlemen took to the Bush and escaped being made prisoners.” After a circuitous tramp through the woods the naval officers rejoined their friends.

Immediately after the council of war on August 6 another express had been sent to Boston with dispatches from the general, but with no report from the commodore. The Navy Board of the Eastern District noticed this omission in a letter to Saltonstall dated August 12, in which they went on to say: “We have for sometime been at a loss to know why the enemy’s ships have not been attacked, nor does the result of this Council give us any satisfaction on that head; it is agreed on all hands that they are at all times in your power. If, therefore, your own security or the more advantageous operations of the army did not require it, why should any business be delayed to another day, that may as well be done this? Our apprehensions of your danger have ever been from a reinforcement to the enemy; you can’t expect to remain much longer without one. Whatever, therefore, is to be done, should be done immediately, both to prevent advantages to the enemy and delays if you are obliged to retreat. As we presume you would avoid having these ships in your rear while a reinforcement appears in front, or the necessity of leaving them behind when you retire yourself; with these sentiments we think it our duty to direct you to attack and take or destroy them without delay, in doing which no time is to be lost, as a reinforcement are probably on their passage at this time. It is therefore our orders that as soon as you receive this you take the most effectual measures for the capture or destruction of the enemy’s ships, and with the greatest dispatch the nature and situation of things will admit of.” (Proc. of Gen. Assembly, 26.) These urgent instructions, signed by William Vernon and James Warren, might possibly have produced some effect, had they been issued and forwarded several days earlier; but it was too late, as was also an application to General Gates for aid, which had recently been made by the Massachusetts Council.

By the time the American forces had been in Penobscot Bay between two and three weeks the fort on Bagaduce peninsula, which at first had been a mere breastwork, was becoming stronger every day and was already a formidable structure. At last, August 13, when General Lovell, hoping for succor from Boston, was still besieging this work and preparing for a possible assault, the enemy’s reinforcements appeared. The Active and Diligent since July 30 had been cruising off “the Mouth of the Bay in order to make the earliest Discoveries of an Enemy’s Approach,” when “on the 13th Inst. 2 P.M. Discovered five Sail Standing into the Bay.” (Mass. Archives, cxlv, 207.) Two others came in sight, making a force of one ship of the line, five frigates and a sloop of war. The Diligent ran in at once to notify the commodore and the Active joined the fleet the next day. There was a disposition at first, no doubt encouraged by the more resolute commanders, to make a stand with the fleet, and the ships were drawn up in the form of a crescent, but at another council it was decided that the British fleet was too strong to engage and that the only alternative must be adopted, which was to run up the river. The captains evidently had no confidence in their leader and little hope of his making a determined resistance.

Meanwhile, upon first receiving information of the approach of British reinforcements, the army had hastily embarked on the transports and the whole fleet made every effort to get as far up the river as possible. All but two of the vessels escaped capture, yet only to be destroyed by their crews after landing, to prevent their falling into the enemy’s hands. The New Hampshire privateer Hampden and the ship Hunter, one of the largest and best of the Massachusetts privateers, were taken by the British. The Hunter was run ashore and her crew escaped before capture. Captain Salter of the Hampden says that when the fleet got under way the enemy was a league and a half astern and that he set all sail, but “my Ship Sailing heavey the enemy Soon came up With me, three frigetes, and fiered upon [me] one after ye outher, & cutt away my rigen & Stages &c, and huld me Sundrey times & wounded Sum of my men. I found it Emposable to Joyane our fleet again; was obliged to Strik, all thou Contray to my well.” (Mass. Archives, cxlv, 44; Wheeler, 302 (Calef’s journal)

The British squadron that caused this reverse of fortune for the American arms consisted of the sixty-four-gun ship Raisonable, two thirty-two-gun frigates, the Blonde and Virginia, the Greyhound of twenty-eight guns, and the Camilla and Galatea of twenty guns each, and the fourteen-gun sloop Otter, and was under the command of Commodore Collier. He received information of the expedition July 28, and sailed from Sandy Hook August 3. According to the log of the Blonde, at half-past twelve in the afternoon of August 15, “the Rebel fleet got under weigh & formed a Line of Battle, we, the Galatea & Virginia being the Headmost ships, the Reisonable, Greyhound & Camilla about 6 or 7 miles a starn.” At half-past one “saw the Rebels forming a Line of Battle; us together with the Virginia & Galatea pursued the 21 sail of Rebels & Drove them before us without the Return of a single shot. At 3 two Ships & a Brigg hauld round to the S. W., trying to get Down the western passage of Long Island; us & the Galatea hauld close to the North End & cut off their Retrait. They then wore & stood after the Body of the fleet; the Galatea Pursued the Brigg & Drove her on shore, we then standing after the Ships & fired several shot at them. At 4 one of the Ships run on shore, ye Galatea sent her 2 Boats to Board her, but finding the Rebels to be armed on the Beach, returned on bd & made sail after us, leaveing them to the Command of our Rere, the Albany, Nautilus & North Just Coming out of Magebacduce River. At 1/2 past 4 fired several shot at the other ship & Huld Her, as did the Virginia. At 5 she struck to us; sent a Boat with an Officer to board Her, which she did, & made sail after us. At 6 upewards of 20 sail of small Vessels run on shore, the most of them they set fire to, which Oblig’d us to anchor.” At seven o’clock the Greyhound got into shoal water and anchored. About the same time the Americans set fire to a sloop and sent her down the river. “Sent 2 Boats man & armed, Cut her Loose & twod Her on shore; sent 3 Boats to Board a schooner & bring her to Anchor, she proved to be Laden with provisions. At 10 saw the Skyrocket on fire, at 1/2 pst saw the Greyhound afloat again; Virginia anchord with the Greyhd 1/2 a mile below us. At 8 Discovered Numbr of small boats passing to & fro from the small Craft to the shore Forts; a Broadside of Round & Grape shot at them. At 9 the Boats returned from ye prize Hamdon of 22 Guns. At 5 A.M. made sigI for all Lieuts that the Boats mand & armed to attack the small Vessels. At 11 made the Signal & weighd, But the wind falling cam, . . . sent the pinnace to Reconnitre the Enemys Vessels.” The next day the Blonde with other British vessels continued the pursuit up the river; they saw the Warren on fire two miles above, “heard the Explosation & saw the smoke of several Vessels on fire above her.” The loss on board the Albany, North, and Nautilus during the siege was trifling: four killed, nine wounded, and eight missing (Brit. Adm. Rec., Captains’ Letters, No. 1612, 2 (Collier, August 20,1779), No. 2121, 16 (Mowatt, September 19, 1779), Captains’ Logs, Nos. 23, 118, 157, 420, 630 (logs of the Albany, Blonde, Camilla, Greyhound and Nautilus)

The British fleet, although carrying fewer men and fewer but doubtless much heavier guns than the American, was far too powerful for an irregular, heterogeneous armament, made up mostly of undisciplined privateers to engage, with any hope of success. Unity of action and mutual support in an emergency could not be expected of such a force. The committee of the Massachusetts General Court, which inquired into the affair, reported, October 7, that the total destruction of the fleet was occasioned principally by “the Commodore’s not exerting himself at all at the time of the retreat in opposing the enemy’s foremost ships in pursuit.” With the pursuing British extended over a long line, a resolute and skillful commander, backed by disciplined and subordinate captains, might have struck a blow of some effect at the enemy; but probably under the circumstances the best course was followed in depriving them of a number of valuable prizes. The fault lay in the earlier, inexcusable inaction. Collier sailed from Sandy Hook August 3. Before that date, if the small British squadron in the bay had been disposed of at the outset and if proper support had been given to the army, General Lovell should have been able to carry the half-finished fort and would probably have been in possession of the whole region, even with his inadequate force. The legislative committee of inquiry expressed the opinion that if Lovell had “been furnished with all the men ordered for the service or been properly supported by the Commodore, he would probably have reduced the enemy”; and added that the naval commanders in the service of the state “behaved like brave, experienced, good officers throughout the whole expedition.” (Boston Gazette, December 27,1779; Proc. of Gen. Assembly, 27-29.)

The need of reinforcing Lovell had been appreciated and when the Massachusetts Council applied to General Gates, August 8, a regiment of the Continental army, of four hundred men, was detailed for this service. They did not get away from Boston, however, until after the disaster at Penobscot. Upon receiving information of this, August 19, they at once put into Portsmouth in the fear of falling in with some of Collier’s ships (lbid., 21; Thacher’s Military Journal, 166-168.) If the inadequacy of Lovell’s force had been realized in the beginning and the reinforcement had been asked for at once, it would have reached the Penobscot in time. The whole affair is a record of blunders and lack of foresight.

Leaving the wrecks of their fleet strewn along the banks of the river, the unhappy soldiers and sailors of the Penobscot expedition found their way back to Boston through the wilderness. The disaster had a depressing effect in Massachusetts. A heavy debt, estimated at seven million dollars, was imposed upon the state, but the humiliation of the affair was felt even more keenly. As General Sullivan said of it, the expense was “not so distressing as the disgrace.” (Sparks MSS., xx, 2.) It has been held that this enterprise was not only mismanaged and doomed to failure, but was ill-conceived and would have been comparatively useless, at least not justifying the cost, even if successful; but another view may perhaps with some reason be entertained. In the first place the establishment of a hostile post within striking distance of Boston naturally caused apprehension and its removal was an object worth considering. Moreover, success justifies much, and more than material advantage is to be considered. In this case victory would have brought prestige to the American arms and would in some degree have inspired confidence in the ultimate happy conclusion of the war, with animating effect on the supporters of the patriotic cause, who had met with much discouragement.

The end of Saltonstall’s career in the Continental service was near. The committee of inquiry reported that the principal reason for the disaster was “want of proper spirit and energy on the part of the Commodore.” (Boston Gazette, December 27, 1779.) It is an interesting question for speculation whether a more “proper spirit and energy ” would have been displayed by Captain Hopkins, who had recently been displaced by Saltonstall in command of the frigate Warren, and who otherwise would doubtless have led the American fleet into Penobscot Bay. A few weeks after the report of the committee, Saltonstall was tried by court martial on board the frigate Deane in Boston Harbor and was dismissed from the navy.

The British held Bagaduce until the end of the war, but they were not entirely unmolested. Just within a year the sting of defeat was in a slight measure alleviated, according to the following account of a small but successful expedition: “A few days ago a detachment from the troops under General Wadsworth went up Penobscot-river, having pass’d the fort in whale-boats in the night, and took two sloops which had been weighing up some of the cannon lately belonging to our privateers which were burnt there. They had got 8 cannon on board and were coming down the river, little expecting to be conducted by our people; but Capt. Mowat had the mortification to see them passing down by the fort, out of his reach however, in triumph. They fired at the fort to vex the enemy and got safe away. Mowat followed them to Campden, but General Wadsworth having drawn up his men and made a breastwork to frighten the enemy, he and his ship were obliged to meach back again, and we are in full possession of the vessels which were intended to invest our coasts. General Wadsworth has taken 40 prisoners, including the men who were on board these vessels.” (Boston Gazette, July 10, 1780; Almon, x, 227.)