Contents

Contents

Chapters

- Chapter 1: The Opening of Hostilities, 1775

- Chapter 2: Naval Administration and Organization

- Chapter 3: Washington’s Fleet, 1775 and 1776

- Chapter 4: The New Providence Expedition, 1776

- Chapter 5: Other Events in the Sea in 1776

- Chapter 6: Lake Champlain, 1776

- Chapter 7: Naval Operations in 1777

- Chapter 8: Foreign Relations, 1777

- Chapter 9: Naval Operations in 1778

- Chapter 10: European Waters in 1778

- Chapter 11: Naval Operations in 1779

- Chapter 12: The Penobscot Expedition, 1779

- Chapter 13: A Cruise Around the British Isles, 1779

- Chapter 14: Naval Operations in 1780

- Chapter 15: European Waters in 1780

- Chapter 16: Naval Operations in 1781

- Chapter 17: The End of the War, 1782 and 1783

- Chapter 18: Naval Prisoners

- Chapter 19: Naval Conditions of the Revolution

- Appendix

The Americans of the eighteenth century were notably a maritime people and no better sailors were to be found. The British colonies were close to the sea, and were distant from each other, scattered along a coast line of more than a thousand miles; so that, in the absence of good roads, intercommunication was almost altogether by water. The ocean trade also, chiefly with England and the West Indies, was extensive. Fishing was one of the most important industries, especially of the northeastern colonies, and the handling of small vessels on the Banks of Newfoundland at all seasons of the year trained large numbers of men in seamanship. The whale fishery likewise furnished an unsurpassed school for mariners.

A considerable proportion of the colonists, therefore, were at home upon the sea, and more than this they were to some extent practiced in maritime warfare. England, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was at war with various foreign nations a great part of the time, and almost from the beginning of the colonial period American privateers and letters of marque scoured the ocean in search of French or Spanish prizes. Large fleets were fitted out and manned by provincials for the expedition under Phips against Quebec in 1690 and for Pepperrell’s successful descent upon Louisburg in 1745. Privateering during the French and Indian War of 1754 furnished a profitable field for American enterprise and gave to many seamen an experience which proved of service twenty years later. Even in times of peace the prevalence of piracy necessitated vigilance, and nearly every merchantman was armed and prepared for resistance (See Weeden’s Economic and Social History of New England, chs. v, ix, xiv, xvi; and Atlantic Monthly, September and October, 1861, for journal of Captain Norton of Newport, 1741. See Appendix I for authorities.)

It would seem, then, that American seamen at the opening of the Revolution had the training and experience which made them the best sort of raw material for an efficient naval force. The lack of true naval tradition, however, and of military discipline, and the poverty of the country, imposed limitations which, together with the overwhelming force of the enemy, seriously restricted the field of enterprise. Nevertheless, the patriotic cause was greatly aided and independence made possible by the activities of armed men afloat.

The navigation laws of Great Britain were naturally unpopular in the colonies, and their stricter enforcement after the peace of 1763, together with the imposition of new customs duties, led to almost universal efforts to evade them. In 1764 the British schooner St. John was fired upon by Rhode Islanders, and in 1769 the armed sloop Liberty, engaged in the suppression of smuggling, made herself so obnoxious to the people of Newport that they seized and burned her. In 1772 the schooner Gaspee, on similar duty, was stationed in Narragansett Bay and caused great annoyance by stopping and examining all vessels. The people were exasperated at the arrogant behavior of her commander, who in many cases exceeded his authority. On the 9th of June, as the Gaspee was chasing a vessel bound from Newport to Providence, she ran aground about seven miles from Providence; she was hard and fast and the tide was ebbing. After nightfall a party of men in boats descended the river from Providence and attacked the schooner. After a short contest, in which the commanding officer of the Gaspee was wounded, she was captured. The prisoners and everything of value having been removed, she was set on fire and in a few hours blew up. Little effort was made to conduct this affair secretly, and yet in spite of the diligent inquiry of a court of five commissioners, all of whom were in sympathy with the British ministry, no credible evidence could be adduced implicating any person; showing a practical unanimity of feeling in the colony (R. I. Colony Records, vi, 427-430, vii, 55-192; Bartlett’s Destruction of the Gaspee; Staple’s Destruction of the Gaspee; Channing’s United States, iii, 124-127, 151.)

The first public service afloat, under Revolutionary authority, was perhaps the voyage of the schooner Quero, of Salem, Captain John Derby, despatched to England by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress with the news of the Battle of Lexington. She sailed April 29, 1775, some days later than General Gage’s official despatches and arrived at her destination nearly two weeks ahead of them (Essex Institute Collections, January, 1900; Century Magazine, September, 1899.)

Early in May, 1775, the British sloop of war Falcon of sixteen guns, Captain John Linzee, seized two American sloops in Vineyard Sound; “on which the People fitted out two Vessels, went in Pursuit of them, retook and brought them both into a Harbour, and sent the Prisoners to Taunton Gaol.” (New England Chronicle, May 18, 1775; American Archives, Series IV, ii, 608.)

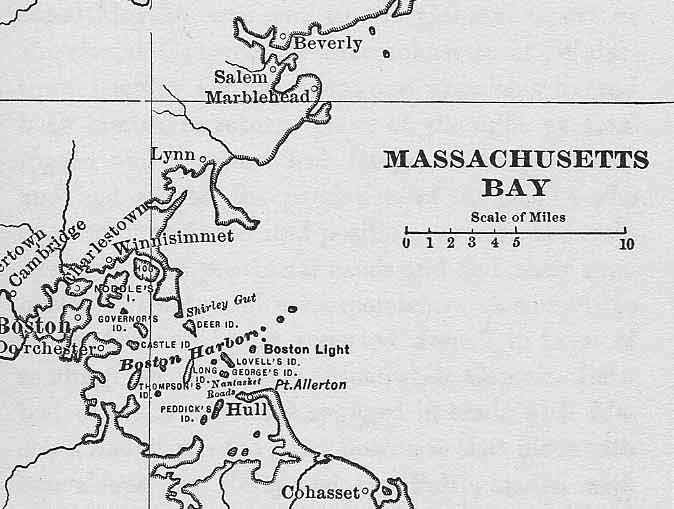

The islands in Boston Harbor had long been used by the colonists for pasturage and were well stocked with cattle and sheep which the British troops in the town took measures to secure for their consumption. Soon after the battle of Lexington they succeeded in carrying off all the livestock on Governor’s and Thompson’s Islands. The Americans, May 27, with the intention of forestalling similar raids, landed between two and three hundred men on Hog Island who attempted to bring off the cattle and sheep, while a detachment of about thirty men crossed over to Noddle’s Island (East Boston) for the same purpose, when “about a hundred Regulars landed upon the last mentioned and pursued our Men till they had got safely back to Hog Island; then the Regulars began to fire very briskly by Platoons upon our Men. In the mean time an armed Schooner with a Number of Barges came up to Hog Island to prevent our People’s leaving said Island, which she could not effect; after that several Barges were towing her back to her Station, as there was little Wind and flood Tide. Our People put in a heavy Fire of small Arms upon the Barges, and two 3 Pounders coming up to our Assistance began to play upon them and soon obliged the Barges to quit her and to carry off her Crew; After which our people set Fire to her, although the Barges exerted themselves very vigorously to prevent it. She was burnt [the next day] upon the Way of Winisimet Ferry. We have not lost a single Life, although the Engagement was very warm from the armed Schooner (which mounted four 6 Pounders and 12 swivels), from an armed Sloop that lay within Reach of Small Arms, from one or two 12 Pounders upon Noddle’s Island, and from the Barges which were all fixed with swivels.” (Boston Gazette, June 5,1775.) The American loss was four wounded, one of whom died two days later; that of the British was said to be twenty killed and fifty wounded. The stock, amounting to over four hundred sheep, about thirty cattle and some horses, were brought away by the provincials. During the siege of Boston various other attempts, successful and unsuccessful, were made to bring away live stock from the islands of the harbor, thereby reducing the possible sources of food supply of the British shut up in the town (Sumner’s History of East Boston, 367-389; Frothingham’s Siege of Boston, 108, 109, 225; Green’s Three Military Diaries, 86; Almon’s Remembrancer, i, 112; Amer. Archives, IV, ii, 719; Boston Gazette, June 5, 1775; N. E. Chronicle, May 25, June 15, July 27, October 5, 1775.)

Josiah Quincy in a letter to John Adams, dated September 22, 1775, proposed a plan for making the investment of Boston complete and so forcing the capitulation of the besieged British army. His proposal was to build five forts, three of them on Long Island, so placed as to command the channels of the harbor, including the narrows which were guarded by the enemy’s men-of-war in Nantasket Roads; these ships could be driven out by the fire of the forts. He would then sink hulks in the narrows. No ships could thenceforth pass in or out and “both Seamen and Soldiers, if they don’t escape by a timely Flight, must become Prisoners at Discretion.” Quincy also thought that “Row Gallies must be our first mode of Defence by Sea.” (Adams MSS.)

Near the eastern frontier of Maine, in a situation most exposed to British attack, lay the little seaport of Machias. The one staple of the town was lumber, and this the inhabitants exchanged at Boston for the various supplies they needed. In the spring of 1775 food was scarce, for the previous year’s crops had failed. Consequently a petition, dated May 25, was sent to the General Court or Provincial Congress of Massachusetts at Watertown, begging for provisions and promising to send back lumber in return. News of the fight at Lexington and Concord had lately reached Machias and had stirred the patriotism of the people, who in spite of their isolated position, were in the main devoted to the provincial cause and had their committee of safety and correspondence. A committee of the General Court reported June 7 in favor of sending the provisions. Meanwhile Captain Ichabod Jones, a merchant engaged in trade with Machias, had proceeded from Boston to that place with two sloops, the Unity and the Polly, loaded with provisions and escorted by the armed schooner Margaretta under the command of Midshipman Moore of the British navy. They arrived June 2 and Jones took measures to procure a return cargo of lumber for the use of the British troops in Boston. As the only means of obtaining the much needed provisions it was voted in town meeting, notwithstanding the opposition of a large minority of staunch patriots, to allow Jones to take his lumber. He proceeded accordingly to distribute the provisions, but to those only who had voted in his favor. The patriots, under the lead of Benjamin Foster and Jeremiah O’Brien, were determined to prevent the shipping of the lumber to Boston. On Sunday, June 11, an unsuccessful attempt was made to capture Jones and the officers of the Margaretta while at church. They took the alarm and Jones fled to the woods, where he was taken some days later; the officers escaped to their vessel. Moore then threatened to bombard the town (Coll. Maine Hist. Soc., vi (April, 1895), 124-130.)

“Upon this a party of our men went directly to stripping the sloop [Unity] that lay at the wharf and another party went off to take possession of the other sloop which lay below & brought her up nigh a wharf & anchored in the stream. The Tender [Margaretta] did not fire, but weighed her anchors as privately as possible and in the dusk of the evening fell down & came to within musket shot of the sloop, which obliged our people to slip their cable & run the sloop aground. In the meantime a considerable number of our people went down in boats & canoes, lined the shore directly opposite to the Tender, & having demanded her to surrender to America, received for answer, ‘fire & be damn’d’; they immediately fired in upon her, which she returned and a smart engagement ensued. The Tender at last slipped her cable & fell down to a small sloop commanded by Capt. Tobey & lashed herself to her for the remainder of the night. In the morning of the 12th she took Capt. Tobey out of his vessel for a pilot & made all the sail they could to get off, as the wind & tide favored; but having carried away her main boom and meeting with a sloop from the Bay of Fundy, they came to, robbed the sloop of her boom & gaff, took almost all her provisions together with Mr. Robert Avery of Norwich in Connecticut, and proceeded on their voyage. Our people, seeing her go off in the morning, determined to follow her.

“About forty men armed with guns, swords, axes & pitch forks went in Capt. Jones’s sloop under the command of Capt. Jeremiah O’Brien; about twenty, armed in the same manner & under the command of Capt. Benj. Foster, went in a small schooner. During the chase our people built them breastworks of pine boards and anything they could find in the vessels that would screen them from the enemy’s fire. The Tender, upon the first appearance of our people, cut her boats from her stern & made all the sail she could, but being a very dull sailor they soon came up with her and a most obstinate engagement ensued, both sides being determined to conquer or die; but the Tender was obliged to yield, her Capt. was wounded in the breast with two balls, of which wounds he died next morning. Poor Mr. Avery was killed and one of the marines, and five wounded. Only one of our men was killed and six wounded, one of which is since dead of his wounds. The battle was fought at the entrance of our harbour & lasted for near the space of one hour. We have in our possession four double fortifyed three pounders & fourteen swivels and a number of small arms, which we took with the Tender, besides a very small quantity of ammunition.” (Coll. Maine Hist. Soc., vi, 130, 131 (report of Machias Committee of Correspondence, June 14, 1775). Foster’s schooner is said to have run aground and to have taken no part in the battle. The Unity returned to Machias with the Margaretta as her prize. O’Brien’s five brothers were with him in this enterprise (Coll. Maine Hist. Soc., 1847, January, 1891, April, 1895; New England Magazine, August, 1895; Massachusetts Magazine, April, 1910; Sherman’s Life of Jeremiah O’Brien, chs. ii-v; Boston Gazette, July 3, 1775.)

Joseph Wheaton, one of the Unity’s crew, wrote many years later a detailed account of the action. He says that the Margaretta, after having replaced her broken boom, “was Making Sail when our Vessel came in Sight; then commenced the chace, a Small lumber boat in pursuit of a well armed British vessel of war – in a Short time she cut away her three boats. Standing for sea while thus pursuing, we aranged our selves, appointed Jeremiah Obrien our conductor, John Steele to steer our Vessel, and in about two hours we received her first fire, but before we could reach her she had cut our rigging and Sails emmencely; but having gained to about one hundred yards, one Thomas Neight fired his wall piece, wounded the man at the helm and the Vessel broached too, when we nearly all fired. At this moment Captain Moore imployed himself at a box of hand granades and put two on board our Vessel, which through our crew into great disorder, they having killed and wounded nine men. Still two ranks which were near the prow got a second fire, when our bowsprit was run through the main shrouds of the Margarette and Sail, when Six of us Jumped on her quarter deck and, with clubed Muskets drove the crew from their quarters, from the waist into the hold of the Margarette; the Capt. lay mortally wounded, Robert Avery was killed and eight marines & Saylors lay dead on her deck, the Lieutenant wounded in her cabin. Thus ended this bloody affray.” (Adams MSS., Wheaton to President Adams, February 21, 1801. See another account by Wheaton in Coll. Maine Hist. Soc., ii (January, 1891), 109.) Wheaton says that fourteen of the Americans were killed and wounded.

According to the British account the Americans attempted to board the Margaretta with boats and canoes during the night before the battle, but were beaten off. In the next day’s chase Foster’s schooner continued in company with the Unity to the end. As these vessels approached they were received by the Margaretta with a broadside of swivels, small arms, and hand grenades, but they both came alongside, the Unity on the starboard and the schooner on the larboard bow (British Admiralty Records, Admirals’ Despatches 485, July 24, 1775, No. 2.)

The General Court of Massachusetts resolved, June 26, 1775: “That the thanks of this Congress be, and they are hereby given to Capt. Jeremiah O’Brien and Capt. Benjamin Foster and the other brave men under their command, for their courage and good conduct in taking one of the tenders belonging to our enemies and two sloops belonging to Ichabod Jones, and for preventing the ministerial troops being supplied with lumber; and that the said tender, sloops, their cargoes remain in the hands of the said captains O’Brien and Foster and the men under their command, for them to improve as they shall think most for their and the public advantage until the further action of this or some future Congress.” (Coll. Maine Hist. Soc., vi, 132.) The Unity was fitted out with the Margaretta’s guns, renamed the Machias Liberty and put under Jeremiah O’Brien’s command; she was presumably chosen as a cruiser in preference to the Margaretta, on account of her superior sailing qualities.

About a month after the capture of the Margaretta the British schooner Diligent, carrying eight or ten guns and fifty men, and the tender Tapnaquish, with sixteen swivels and twenty men (Wheaton (Adams MSS.) gives these vessels a smaller number of men and guns), appeared off Machias. The captain of the Diligent going ashore in his boat was seized by a small party of Americans stationed near the mouth of the bay and sent to Machias. Jeremiah O’Brien in the Machias Liberty and Benjamin Foster in another vessel were then sent down the river, found the British vessels and took them without firing a gun. According to Wheaton, O’Brien subsequently cruised in the Bay of Fundy and took a number of British merchant vessels (Coll. Maine Hist. Soc., ii (1847), 246, ii (January, 1891), 111; Life of O’Brien, ch. vi; Massachusetts Mag., January, 1910.)

Foster and O’Brien were next sent by the Machias Committee of Safety to Watertown to report their exploits to the Provincial Congress. Under their charge went also the prisoners taken in the Margaretta, Diligent and Tapnaquish together with Ichabod Jones. They proceeded as far as Falmouth (Portland), a week’s voyage, by water. The ruthless burning of Falmouth by the British under Captain Henry Mowatt several weeks later is supposed to have been, in part at least, an act of retaliation for the capture of the British vessels at Machias. The journey of O’Brien and Foster from Falmouth to Watertown was made by land and took about ten days. On August 11th the prisoners were delivered at Watertown by their captors, who about the same time reported also to General Washington at the headquarters of the army in Cambridge. They petitioned the Provincial Congress for the privilege of raising a company of men among themselves at the expense of the Province, to be used in the defense of Machias and to give occupation to numbers of young men who in the distress of war times were without means of support. They also asked that the officers of the Machias Liberty be given commissions and that men be stationed on board her, this vessel to be supplied and equipped and used for the defense of the town, which might easily be blockaded by a small force. The petitions were favorably received by the Congress and O’Brien was appointed to command both the Machias Liberty and the Diligent. These vessels were thereby taken into the service of the colony and became the nucleus of the Massachusetts navy. O’Brien soon returned to Machias in order to oversee the fltting out of his vessels (O’Brien, ch. vi; Am. Arch., IV, iii, 346, 354; Records of General Court of Massachusetts, August 21, 23,1775; Massachusetts Spy, August 16, 1775.)

Off Cape Ann, August 9, 1775, the British sloop of war Falcon, Captain Linzee, fell in with two schooners from the West Indies, bound to Salem. One of these schooners, says a report from Gloucester, was “soon brought to, the other taking advantage of a fair wind, put into our harbour, but Linzee having made a prize of the first, pursued the second into the harbour and brought the first with him. He anchored and sent two barges with fifteen men in each, armed with muskets and swivels; these were attended with a whale boat in which was the Lieutenant and six privates. Their orders were to seize the loaded schooner and bring her under the Falcon’s bow. The Militia and other inhabitants were alarmed at this daring attempt and prepared for a vigorous opposition. The barge-men under the command of the Lieutenant boarded the schooner at the cabbin windows, which provoked a smart fire from our people on the shore, by which three of the enemy were killed and the Lieutenant wounded in the thigh, who thereupon returned to the man of war. Upon this Linzee sent the other schooner and a small cutter he had to attend him, well armed, with orders to fire upon the damn’d rebels wherever they could see them and that he would in the mean time cannonade the town; he immediately fired a broadside upon the thickest settlements and stood himself with diabolical pleasure to see what havock his cannon might make . . . Not a ball struck or wounded an individual person, although they went through our houses in almost every direction when filled with women and children . . . Our little party at the waterside performed wonders, for they soon made themselves masters of both the schooners, the cutter, the two barges, the boat, and every man in them, and all that pertained to them. In the action, which lasted several hours, we lost but one man, two others wounded, one of which is since dead, the other very slightly wounded. We took of the men of war’s men thirty-five, several were wounded and one since dead; twenty-four were sent to head-quarters, the remainder, being impressed from this and the neighboring towns, were permitted to return to their friends.” (Pennsylvania Packet, August 28, 1775; N. E. Chronicle, August 25, 1775.)

Captain Linzee, who makes the date of the affair August 8, states in his report to the admiral at Boston that having anchored in Gloucester harbor he “sent Lieut. Thornborough with the Pinnace, Long Boat and Jolly Boat, mann’d and arm’d in order to bring the Schooner out, the Master coming in from sea at the same time in a small tender, I directed him to go and assist the Lieutenant. When the Boats had passed a Point of Rocks that was between the Ship and Schooner, they received a heavy fire from the Rebels who were hidden behind Rocks and Houses, and behind Schooners aground at Wharfs, but notwithstanding the heavy fire from the Rebels, Lieut. Thornborough boarded the Schooner and was himself and three men wounded from Shore. On the Rebels firing on the Boats, I fired from the ship into the Town, to draw the Rebels from the Boats. I very soon observed the Rebels payed little attention to the firing from the ship and seeing their fire continued very heavy from the schooner the Lieutenant had boarded, I made an attempt to set fire to the Town.” Hoping that by this means the attention of the Americans would be directed to saving their houses, so that the schooner could be brought off, Linzee sent a party ashore to fire the town; but the powder used for the purpose was set off prematurely, “one of the Men was blowed up,” and the attempt failed. The town was then bombarded. “About 4 o’clock in the afternoon the lieutenant was brought on board under cover of the Masters’ fire from the Schooner, who could not leave her. All the Boats were much damaged by the shots and lay on the side of the Schooner next to the Rebels; on my being acquainted with the situation of the Master, I sent the Prize Schooner to anchor ahead the Schooner the Master was in and veer alongside to take him and People away, who were very much exposed to the Rebels’ fire, but from want of an officer to send her in, it was not performed, the Vessel not anchored properly.” The master, despairing of succor, surrendered about seven in the evening “with the Gunner, fifteen Seamen, Seven Marines, one Boy, and ten prest Americans.” The next morning the Falcon weighed anchor and proceeded to Nantasket Roads (Magazine of History, August, 1905.)

Several other affairs, of little importance in themselves, showed the readiness of the provincials for action upon the water at an early period, before there was naval organization of any kind to give authority to their acts (Boston Gazette, September 11, October 2, 9, 1775; Penn. Packet, September 4, 1775.) Boston being the seat of war at this time, most of the maritime events naturally took place in New England waters during the first year. As early as August, 1775, however, a South Carolina sloop, sent out by the Council of Safety, captured a British vessel on the Florida coast (Am. Arch., IV, iii, 180.)

The situation of affairs in America, as is well known, caused great concern in England for a considerable time before the actual outbreak of the rebellion. Of all the measures proposed by whig or tory for the adjustment of the difficulty, probably the wisest, for the conservation of the empire, was suggested by Viscount Barrington, the Secretary at War; but wisdom availed little with the British ministry of that day. Barrington’s advice was given in a series of letters written in the years 1774 and 1775 to the Earl of Dartmouth, Secretary for the Colonies (Political Life of William Wildman, Viscount Barrington, by his brother Shute (London, 1814), 140-152.) His opinion was that the colonies could not be subdued by the army, and that even if they could, the permanent occupation of America by a large force would be necessary, a source of constant exasperation to the colonists and of enormous expense to the government. The troops, he thought, should be withdrawn to Canada, Nova Scotia, and East Florida, and there quartered “till they can be employed with good effect elsewhere.” The reduction of the rebellious colonies should be left to the navy. November 14, 1774, he writes: “The naval force may be so employed as must necessarily reduce the Colony [Massachusetts] to submission without shedding a drop of blood.” (Ibid., 141.) A few weeks later, December 24, he goes a little more into detail. Speaking especially of New England he says: “Conquest by land is unnecessary, when the country can be reduced first by distress and then to obedience by our Marine totally interrupting all commerce and fishery, and even seizing all the ships in the ports, with very little expense and less bloodshed.” As to the colonies south of New England, “a strict execution of the Act of Navigation and other restrictive laws would probably be sufficient at present.” A few frigates and sloops could enforce those laws and prevent almost all commerce – “Though we must depend on our smaller ships for the active part of this plan, I think a squadron of ships of the line should be stationed in North America, both to prevent the intervention of foreign powers and any attempt of the Colonies to attack our smaller vessels by sea.” “The Colonies will in a few months feel their distress; their spirits, not animated by any little successes on their part or violence of persecution on ours, will sink; they will be consequently inclined to treat, probably to submit to a certain degree.” (Barrington, 144-147.) Concessions could then be made without loss of dignity, the mistake of imposing further obnoxious taxes being avoided. Barrington wrote on the same subject to Dartmouth the next year; and also to Lord North, August 8, 1775, saying: “My own opinion always has been and still is, that the Americans may be reduced by the fleet, but never can be by the army.” (Ibid., 151)