Contents

Contents

The Battle of Monmouth was fought at Monmouth Courthouse, near Freehold and Manalapan, New Jersey, on June 28, 1778.

This was one of the largest battles of the Revolutionary War with around 20,000 troops involved, and resulted in a stalemate, with roughly equal numbers of casualties on both sides.

Summary

Leadup

In February 1778, following the Battles of Saratoga, the French officially joined the Revolutionary War on the American side.

This development forced the British Army to change its military strategy.

While the British decided to be more aggressive in the south, where they felt the Patriots were weakest, Redcoat leaders chose to implement a more cautious, defensive strategy further to the north.

Lieutenant General Henry Clinton was appointed Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America in February 1778, under orders to implement a more defensive strategy.

After formally taking command in May, Clinton decided to leave the British stronghold at Philadelphia, and instead move up to New York, which was considered a more strategically important location.

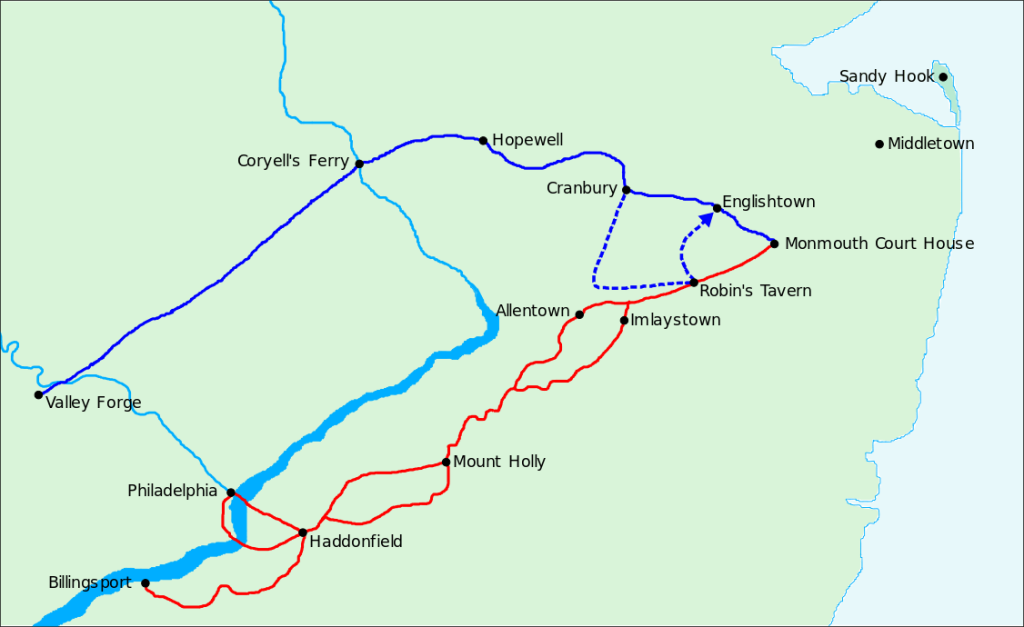

He therefore set off to the north-east on June 15th, planning to reach Sandy Hook, New Jersey, before sailing across the bay to New York City.

Meanwhile, the Continental Army under the command of George Washington was following the British, hoping to cut off their march.

The previous winter, Washington camped with his men at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Here, as the weather warmed up, he made significant progress in training and re-energizing his troops, with the help of Prussian army officer Baron von Steuben.

With the French now helping out, Washington wanted to strike a blow to Clinton’s forces, countering his defensive strategy with a more aggressive approach.

In total, the British march numbered about 19,000 men, split into two divisions – though only the first division (about half of the men) would see combat.

By contrast, the Americans numbered about 14,000 troops, with roughly 10,000 involved at the Battle of Monmouth.

Battle

On June 28, 1778, the Continental Army intercepted the British as they were moving through Freehold, New Jersey.

Clinton was aware of the incoming American approach, and decided to set up his troops near Monmouth Courthouse.

First contact was made by an advance force of Continental troops on June 28, under the command of General Charles Lee.

Lee’s men attacked the British rear guard in the morning, but soon found themselves outnumbered – Clinton had ordered an extra force under the command of General Charles Cornwallis to go back and bolster their numbers.

Facing the risk of being overrun, Lee ordered a retreat.

Washington soon arrived in advance of his men, and saw Lee’s troops falling back in complete disarray.

Furious, he stripped Lee of his command in the field, and with the help of Generals Anthony Wayne and Nathanael Greene, Washington reorganized his men into proper formation, before launching a counterattack.

Intense fighting continued throughout the afternoon, with both sides relying heavily on their artillery.

It was a hot, humid summer day, and by nightfall, with both sides exhausted, the fighting died down, though Washington had made progress in moving his artillery forward to threaten Clinton’s men.

With the primary objective of reaching New York to consolidate his forces, Clinton retreated under the cover of darkness. Washington chose not to pursue him, realizing that his men were completely exhausted.

Ultimately, both sides suffered around 500 casualties each.

Significance

Though it was not a resounding victory, the Battle of Monmouth demonstrated the efficacy of Washington and von Steuben’s training at Valley Forge.

The result proved that the Continental Army was an organized, disciplined fighting force that could take on the British Army.

Despite the initial difficulties General Lee’s men faced, once Washington arrived, the Americans successfully reorganized, and made inroads against the British position.

Monmouth was also a morale boost for the Americans. Partly because it showed that their months of training had been a success, and partly because it finalized the abandonment of Philadelphia by the British, which was a significant embarrassment for Clinton.

Facts

- After the battle, American soldiers recounted the Legend of Molly Pitcher, a woman who took up responsibility for manning a cannon after her husband was wounded or killed in action. Some historians believe that this woman was Mary Ludwig Hays, wife of a member of the Pennsylvania State Artillery.

- Most of the casualties of the battle were attributed to fatigue and heatstroke, not artillery, musket, or rifle fire.

- Clinton made it to Sandy Hook on July 6, and continued safely to New York. He was just in time – five days later, a powerful French naval fleet under Admiral Charles Henri Hector d’Estaing arrived at Sandy Hook.

- Both sides claimed victory at Monmouth, though most historians describe the result as inconclusive, with neither side achieving an outright victory.

- General Lee soon returned to his role as second-in-command to Washington, but was furious about being blamed for the retreat. He wrote insulting letters to Washington, who responded by having him court-martialed. He was found guilty of disobeying orders, ordering a “shameful” retreat, and disrespecting his commander-in-chief, but was given a light sentence – a year’s suspension from the army.