Contents

Contents

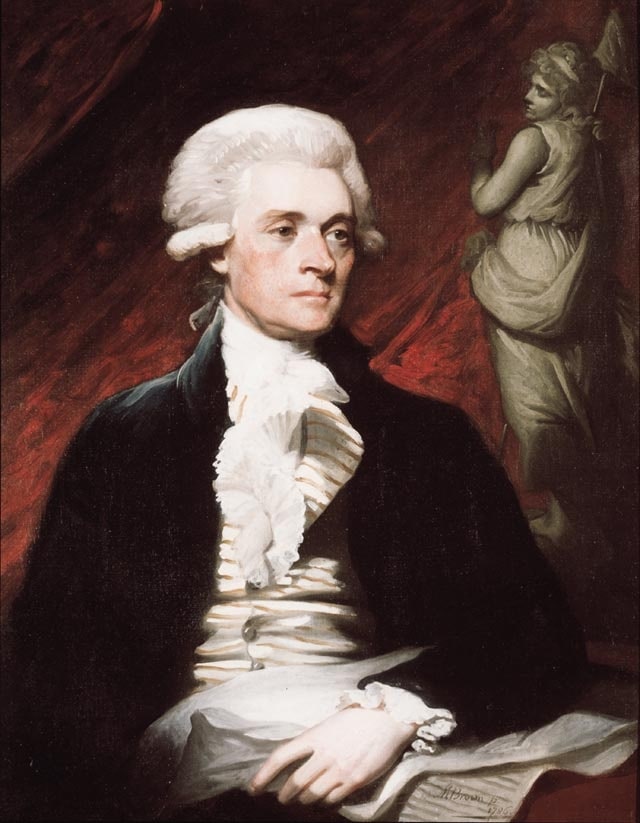

Thomas Jefferson played a crucial role in the Patriot cause as a political leader and writer during the Revolutionary War.

Leadup to Revolution

In 1769, Thomas Jefferson, a young, well-educated lawyer, joined the House of Burgesses, marking his entrance into the political sphere.

The House of Burgesses was Virginia’s colonial parliament, and as a new member, Jefferson watched as the representatives fought back against unjust British legislation, such as the Townshend Acts.

Jefferson quickly began to align himself with the Patriot side of politics, endorsing movements and petitions to oppose the actions of the British government. He soon began writing his own arguments, and advocating for the rights of American colonists.

In 1773, Jefferson worked with Francis Lightfoot Lee, Patrick Henry, and other Virginian politicians to create the colony’s committee of correspondence, which organized resistance against British overreach with the rest of the Thirteen Colonies.

The year after, when the Coercive Acts were introduced, Jefferson decided to stop practicing as a lawyer and focus full-time on politics.

In response to the Acts, he helped organize a day of “Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer” among the members of the House of Burgesses, in protest of British actions against Massachusetts and Boston.

Even though the Coercive Acts predominantly affected Massachusetts, Jefferson and other Patriot leaders wanted Virginia to become involved in this issue in order to put pressure on the British Crown.

The House of Burgesses passed the following resolution in May 1774, drafted with Jefferson’s help:

Being deeply impressed with apprehension of the great dangers, to be derived to British America, from the hostile Invasion of the City of Boston, in our Sister Colony of Massachusetts Bay, whose commerce and harbour are, on the first Day of June next, to be stopped by an Armed force, deem it highly necessary that the said first day of June be set apart, by the members of this House as a day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer…

Throughout the rest of 1774, Jefferson continued in his role as a Patriot ideological leader, arguing that British actions in the colonies were illegal.

In the second half of that year, he published A Summary View of the Rights of British America, which argued that the British Parliament had no legal authority over the colonies, and framed the dispute as a violation of the colonists’ rights under British law.

He argued that the act of government required the consent of the governed, and that the colonies were independent entities with their own legislatures, founded independently from Great Britain.

Jefferson’s arguments were used extensively by the Patriot movement to argue against British taxation and overreach, and to garner support for their cause.

War begins

Jefferson did not participate in the First Continental Congress from September to October 1774, as he fell ill with dysentery while traveling to the convention where the election of Virginia’s political representatives was to take place.

However, Jefferson did join the Second Continental Congress, which first convened on May 10, 1775.

One of Jefferson’s first actions was to draft the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, which provided the reasons why the Patriots believed it necessary to begin forming armed militia groups in response to British hostility.

Once again, Jefferson’s writing was persuasive and effective, and helped to solidify the Second Continental Congress’s justification for entering into armed conflict.

The Declaration of Independence

Jefferson’s greatest contribution to the Revolutionary War effort, and arguably to America as a whole, was to draft the Declaration of Independence.

In June 1776, Congress appointed the Committee of Five – a group of leading Patriot politicians who would write this crucial document. Their goal was to justify the righteousness of the Revolution, assert America’s independence as a country, and begin attracting foreign aid from other nations such as France and the Netherlands.

Jefferson, renowned for his writing, was made responsible for the first draft of the Declaration, which he wrote in Philadelphia from June 11 to June 28.

This draft was then reviewed by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Sherman. A portion of Jefferson’s original text was removed, which argued against the slave trade and disparaged King George III for perpetuating the industry, in order to keep southern delegates from colonies such as South Carolina onside.

After these changes were made, the document was formally adopted on July 4, 1776.

Virginia governance

Jefferson left Congress in late 1776 to return to the Virginia state government.

During this time, he helped draft laws that helped transform the region from a colony of Great Britain into an independent state, creating legislation and social structures covering areas such as education, property inheritance, and religious freedom.

Eventually, Jefferson became the Governor of Virginia in 1779, serving for two consecutive terms until June 1781.

During his time as Governor, Virginia was under constant threat of British invasion, and defense was Jefferson’s most important responsibility.

However, the new Governor received criticism for some of the military strategy decisions he made during this time.

- He implemented conscription to raise troop numbers, which was extremely unpopular.

- He was sometimes accused of being slow to act in response to British movements, for example when the British Army marched towards Richmond in December 1780 and January 1781.

- He rarely if ever chose to go on the front foot against the British, instead generally opting to retreat, which led to the state government being driven out of Charlottesville in June 1781.

Jefferson’s reputation suffered as a result of his performance as Governor of Virginia. His lack of military experience led to several failings of leadership in this role, and he would not seek to return to a position involving military matters for the remainder of the war.

However, as Governor, Jefferson was somewhat restricted by the Virginia state constitution of 1776, which gave him relatively little authority in this position. As a result, he was limited in what he could do to respond to British offensives in the state during the war.

End of the war

After leaving his role as Governor of Virginia, Jefferson withdrew somewhat from public life. He went to his estate at Monticello, and began writing Notes on the State of Virginia – a book that explains and provides data on various aspects of the state, such as its natural resources, society, and economics.

The book also argued that Black and White people could not be seen as equals – Jefferson owned more than six hundred slaves throughout his lifetime, though he did argue that slavery should be abolished multiple times during his career.

Jefferson returned to the Virginia House of Delegates briefly in late 1781 to respond to an inquiry into his conduct as Governor. In the end, the claims against Jefferson were found to be baseless, and the former Governor was formally thanked for his leadership by the assembly.

On September 6, 1782, Jefferson’s wife Martha died, which left him devastated, causing him to withdraw even further in the immediate aftermath.

In 1783, Jefferson was appointed to serve as a diplomat responsible for negotiating for peace with Great Britain. However, he did not make it to France in time to participate in the talks, as an agreement had already been reached before he could leave America.

Jefferson did however travel to Paris the year after, serving as American Minister to France from 1785 until 1789.