Contents

Contents

The Saratoga Campaign was a series of battles fought between the British and Continental Armies in 1777 during the Revolutionary War.

The campaign was a failure for the British Army, ending in American victory and significant British losses at the Battles of Saratoga, with the result convincing the French to officially join the war on the American side.

Context

In 1777, the British decided to implement a new military strategy in their fight against the Continental Army.

They believed that Patriot sentiment was relatively weak in the southern colonies in America, compared to in rebel strongholds in New England.

The British thought that when they later moved to capture southern cities, the local populations would rise up against the Continental Army.

As a first step, the British aimed to cut off New England from the middle and southern colonies, to isolate what they thought were the strongest areas of colonial resistance.

After the failed American invasion of Canada (1775-76), the Americans were on the back foot, and it seemed the perfect time to begin the Saratoga Campaign.

British forces rested for the winter of 1776-77, then prepared for action.

The plan

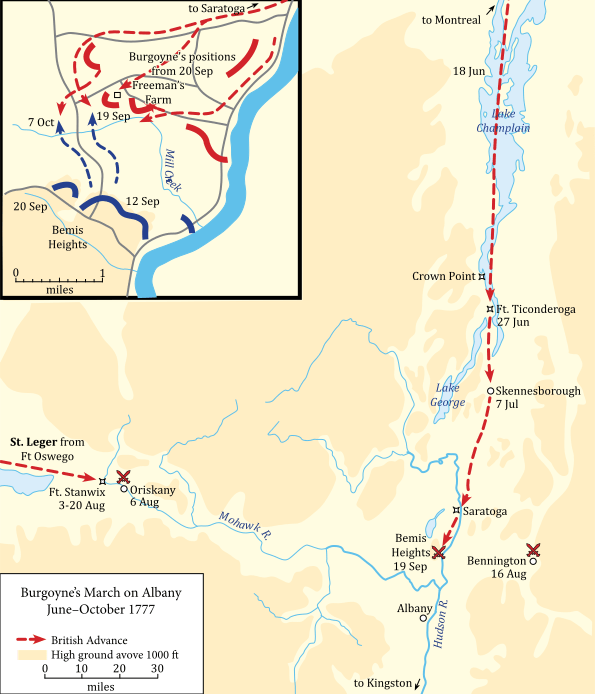

The British planned to attack Albany, New York, in order to cut off the New England colonies.

The attack was planned as a pincer movement, converging on Albany from three directions:

- From Montreal, Canada, Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger and his 2,000 men would march south down the St. Lawrence River, and attack Albany from the west.

- From New York, General William Howe and 13,000 men would march up the Hudson River, and attack Albany from the south.

- From Montreal, Canada, General John Burgoyne and his 8,000 men would march south following Lake Champlain, and attack Albany from the north.

The plan, masterminded by Burgoyne, was ambitious. A huge effort would be required to maintain the necessary supply lines for more than 20,000 troops in total, especially the ones making the journey from Canada.

Unfortunately for the British, the plan fell apart, with all three prongs of the attack soon running into difficulty.

1. St. Leger and the Siege of Fort Stanwix

St. Leger set sail from Montreal on June 23, 1777, moving across Lake Ontario and onto Oswego, New York.

On August 2, he reached the American defenses at Fort Stanwix, and began a siege on their position.

The Americans were initially outnumbered, but were able to conduct raids on nearby Loyalist and indigenous camps, hurting the morale of Leger’s forces – about half of whom were from the native Mohawk, Seneca, and Cayuga tribes.

Further bolstering the American position, they were soon reinforced by troops under the command of Major General Benedict Arnold.

Arnold staged the release of a supposed Loyalist prisoner-of-war, who was actually a double agent for the Americans.

This double agent convinced the British that Arnold’s forces were much larger than they actually were, causing Leger to withdraw on August 22, retracing his steps back to Oswego and north into Canada.

2. Howe and the march up the Hudson

General Howe did not buy into Burgoyne’s plan to attack Albany.

Instead, he decided to attack Philadelphia, and received approval from British high command to march south instead. It remains unclear whether he knew that Burgoyne was going to execute the plan he described, or whether Howe was completely unaware of the overall strategy.

It is also possible that Howe thought he could take Philadelphia before turning around and helping Burgoyne – he had initially proposed this idea in a letter to Major General George Germain.

However, his movements were relatively slow – he was in no rush to take Philadelphia, which does not support this theory.

Regardless, Howe set off from New York for Pennsylvania, along with the majority of the British manpower in the area, on July 23, 1777.

Later, at the beginning of October, a small brigade under the command of General Sir Henry Clinton began marching north up the Hudson towards Albany in Howe’s absence.

He soon captured Forts Clinton and Montgomery on October 6, and advanced as far north as Kingston 10 days later, about two-thirds of the way between New York and Albany, before turning back.

3. Battles of Saratoga

Burgoyne set off south towards Albany on June 14, 1777.

His men initially made good progress. On July 2, they took the Americans by surprise at Fort Ticonderoga, causing them to retreat, and allowing Burgoyne to capture the position without firing a single shot.

After this point, things began to go downhill for the British marching down Lake Champlain.

Burgoyne began to run into issues with his supply lines. They were moving incredible distances through difficult terrain at a tremendous pace, in order to reach Albany in time to meet up with the other British forces.

The situation was not helped by the fact that Burgoyne decided to travel with 30 wagons of personal luggage, including fine silverware and wine.

However, he thought that Howe would soon arrive, and also believed that he would meet up with St. Leger’s men as well, at least until the end of August.

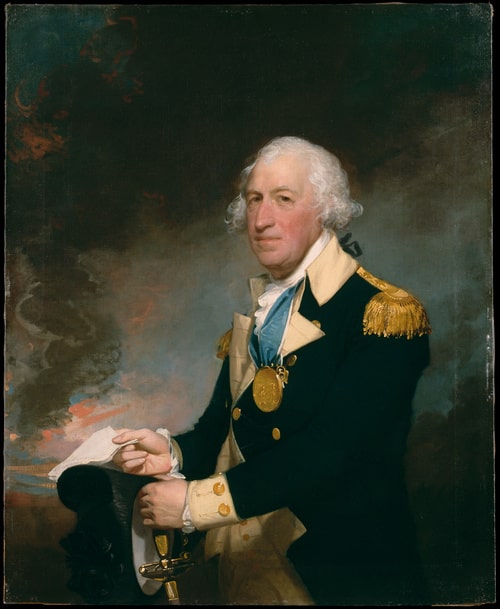

Meanwhile, American forces under the command of Generals Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold were tasked with intercepting Burgoyne’s march. Their troops, totaling approximately 8,500 men, set up fortifications at Bemis Heights to stop the British advance.

The First Battle of Saratoga

On September 19, Burgoyne’s men arrived, commencing the First Battle of Saratoga, just in front of Bemis Heights at a place known as Freeman’s Farm.

The British suffered heavy losses, but were able to take control of the battlefield by nightfall. However, the Americans still controlled Bemis Heights.

Burgoyne considered pushing ahead the next day, but instead decided to consolidate his position, and allow his troops to rest. He was running low on food and other supplies, and was hopeful that reinforcements would soon arrive.

The Americans were also in disagreement about what to do. Arnold wanted to pursue the British aggressively, but Gates was more cautious, fearing that British reinforcements would arrive, and preferring to force the British to attack his fortifications.

This led to a spat between the two men, with Gates relieving Arnold of his command. The Americans ultimately opted to wait, meanwhile receiving a steady stream of troop reinforcements.

The Second Battle of Saratoga

Eventually, Burgoyne realized that help was not on its way. Clinton had left New York with about 3,000 men and pushed north to try and cause a diversion, but was not moving fast enough.

Therefore, Burgoyne decided to launch a last-ditch attack on October 7.

Immediately, the British were pushed back, and began retreating the next day. Eventually, they were surrounded at Saratoga on October 17, forcing Burgoyne to surrender.

Throughout the two battles, the British lost approximately 1,100-1,200 men killed or wounded, plus 6,200 captured at the conclusion of the second battle.

Aftermath

After the Saratoga Campaign, the tide of the American Revolution turned against the British.

Sensing British weakness, and seeing that the Continental Army was a competent fighting force, the French soon decided to officially join the Revolutionary War on the American side, formalizing their entry in February 1778.

Saratoga was a huge psychological boost for the Continental Army under George Washington. French military and naval support proved to be the final piece of the puzzle needed to win the Revolutionary War at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781.

Though less important, the loss of more than 6,000 troops was also a significant blow to the British Army. Most of these men were kept as prisoners of war until 1783, unable to help the British cause for the remainder of the conflict.