Contents

Contents

The Treaty of Paris was a 1783 agreement that officially ended the American Revolutionary War.

Under the Treaty, America was formally surrendered by the British and recognized as an independent country.

Background and context

The American Revolution was effectively won after the Battle of Yorktown, when British General Charles Cornwallis surrendered to American forces on October 19, 1781.

After news of the result reached Great Britain, the country’s will to keep fighting collapsed. There was a vote of no confidence in the Prime Minister, Frederick North, leading him to resign in March 1782.

As a result, while skirmishes continued, no more major battles occurred, and the British decided to enter into peace talks with American leaders. These negotiations began in April 1782 in Paris, France.

Informal peace discussions had occurred previously, but Britain had never been willing to recognize the complete independence of the United States, which was unacceptable to the Founding Fathers. This changed after the Battle of Yorktown.

Negotiations

At the negotiating table, the Americans were predominantly represented by John Jay, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin.

The British were initially represented by Richard Oswald, before he was replaced by David Hartley, a Member of Parliament, and the new Prime Minister, Lord Shelburne, was also involved.

Negotiations were complex, and dragged on through late 1782. The difficulty was that France, Spain, and the Netherlands were also involved in negotiations with the British, as they had all participated in the war (and other concurrent conflicts with Britain) to varying degrees.

France’s foreign minister, Charles Gravier de Vergennes, wanted negotiations handled as a single settlement, so that allies would agree on the result. However, John Jay believed that negotiating together as allies would result in the French pushing for a weaker United States in order to accommodate Spanish priorities, as France was allied with Spain. For example, the Spanish wanted to minimize American expansion to protect their own territorial claims to the west of the Thirteen Colonies.

The British wanted to split the French-American alliance, so speaking directly with American diplomats also made strategic sense from a British point of view.

In September 1782, America and Great Britain began negotiating directly, with unofficial discussions occurring in London.

Though it was soon agreed that America would become independent, the two sides spent months working through issues such as:

- The borders of the new nation (how much territory the British would give up).

- Fishing rights on the Atlantic coast.

- The evacuation of British armed forces.

- Repayment of war debts to British creditors.

- How trade would be conducted between the two nations.

- What would happen to Loyalists in America and their property.

Great Britain wanted to maintain the United States as a trading partner, especially so that the country could continue to purchase goods from British manufacturers.

It was therefore eventually decided to allow America to extend all the way to the Mississippi in the west, rather than the British keeping a slice of territory at the edge of the new country.

It was thought that this would allow the new United States to become a larger trading partner for Great Britain, and would save the British the cost and hassle of continuing to administer this territory.

British negotiators therefore decided to make this concession to the Americans in their direct discussions, which helped the talks to progress.

Eventually, the new United States and Great Britain came to an agreement, and separate arrangements were also made with France, Spain, and the Netherlands.

Contents of the Treaty

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, before being ratified by the United States Congress and the British Parliament the following year.

Under the 10 Articles of the Treaty of Paris:

- Hostilities between the two sides would cease.

- The United States was recognized as a free and independent nation.

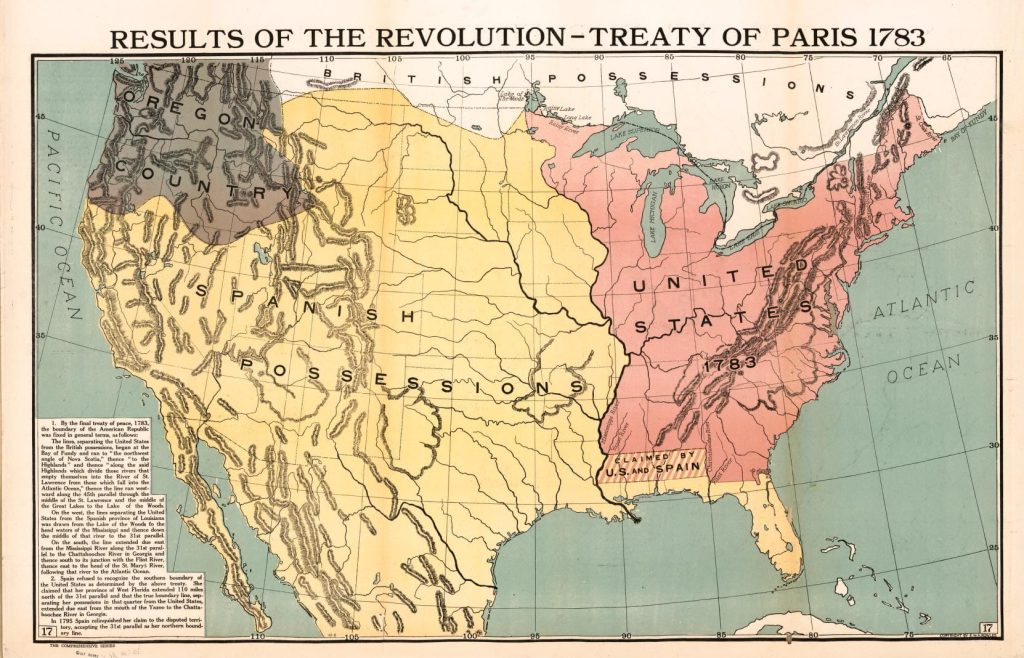

- The border of America extended north to British Canada, east to the Atlantic Ocean, south to Spanish Florida, and west to the Mississippi River.

- The United States and Great Britain were both allowed to freely navigate the Mississippi River.

- The British Army would withdraw peacefully, and would not take enslaved persons or American property with them.

- America retained fishing rights near Newfoundland and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

- Debts between individuals or companies located in the other country were still outstanding, and had to be repaid.

- States were recommended to return Loyalist property, but were not required to do so.

- Prisoners of war were to be released, and soldiers would not face imprisonment or other retribution for their actions during the war.

In the years following the ratification of the Treaty, some aspects of the agreement were ignored or violated, and the document did not relieve tensions between the United States and Great Britain.

Great Britain continued to man many of its forts and outposts in the Great Lakes region, contrary to the provisions of the Treaty. On the American side, Loyalists continued to be treated badly, and most seized property was not returned to its original owners.

The British also allowed slaves who had fled to their lines to leave America for Britain and Canada, which caused anger in the United States as the British withdrew.

Native Americans in particular felt betrayed by the agreement, because lands reserved for them by the British under the Royal Proclamation of 1763 were essentially handed over to the Americans. This led to decades of conflict and displacement as America looked to secure its territory to the west.

Facts

- The language of the Treaty was first agreed upon on November 30, 1782, before being signed on September 3, 1783. In the interim, the British finalized a separate peace treaty with France.

- Under the Treaty of Paris, America doubled in size compared to the prior territorial claims of the Thirteen Colonies.

- Benjamin Franklin’s original position at the beginning of negotiations was that Canada be handed over to the United States, but the British refused this.

- Benjamin West planned to paint a big scene of the signing, but the British representatives reportedly wouldn’t sit for him. The half-finished painting, displayed above on this page, ends up showing just the American delegates.

- Article 1 of the Treaty, which defines America as an independent nation, is still in force to this day.

- The Treaty was signed by three Americans and one Englishman. David Hartley was the signatory for Great Britain, while John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay put pen to paper for the United States.

- Some clauses were intentionally written softly because the U.S. federal government was weak. This included the provision to recommend that Loyalist property be returned to its original owner. At the time, the federal government could not force the states to do this, so the provision was written as a mere suggestion.