Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 11 January 1755 (or 1757) in Charlestown on the island of Nevis in the British West Indies.

- Hamilton was born on the West Indian Island of Nevis, probably in 1755. Hamilton claimed that he was born in 1757, but most historians now believe that he shaved two years off his age — possibly to make himself more attractive for an apprenticeship.

- Born out-of-wedlock to James Hamilton and Rachel Faucett Lavien, his political enemies would never let him forget that he was illegitimate.

- Enrolling in King’s College (now Columbia University) in 1774, Hamilton never graduated; he left to fight Great Britain.

- He raised the New York Provincial Company of Artillery and was elected captain (1775).

- Distinguishing himself at the Battles of Long Island, White Plains, and Trenton in 1776, he became Washington’s aide-de-camp, with the rank of lieutenant colonel, in March 1777 — a position he held for four years.

- He also participated with distinction at the Battle of Monmouth (1778) and the Siege of Yorktown (1781), after which he resigned his commission.

- Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler (1780); they had eight children together.

- He was admitted to the New York bar in 1783.

- He was a delegate to the Continental Congress from 1782 to 1783.

- Hamilton assisted in founding the Bank of New York (1784), which operated uninterrupted for over two centuries. In 2007 the bank merged with the Mellon Financial Corporation to become The Bank of New York Mellon.

- He assisted in founding the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission (release) of Slaves (1785).

- He was one of the 39 signers, and the only one from New York, of the U.S. Constitution (1787).

- Hamilton authored 51 of the 85 essays of the Federalist (1787 – 88).

- He served a term in the Confederation Congress (1788 – 89).

- President Washington appointed him the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury (1789 – 95).

- Hamilton started a daily broadsheet, the New-York Evening Post (1791). It became one of the most successful newspapers in America and today goes by the name of the New York Post.

- After retiring from government service (1795), Hamilton purchased a 32-acre parcel of land in modern-day Harlem in Manhattan — which was then considered a rural suburb of New York. Naming it “the Grange,” in honor of his father’s ancestral home in Scotland, the house was completed in 1802 — nearly bankrupting the family in the process. It was the only home Hamilton ever owned.

- Hamilton’s eldest son, Philip, defending his father’s reputation, was shot in a duel and died the next day (1801).

- Three years later, Hamilton himself was shot in a duel with Aaron Burr on 11 July 1804 and died the next day.

- Died: 12 July 1804 in New York, New York.

- Buried in the churchyard at Trinity Church, New York.

Introduction

Alexander Hamilton, American statesman and the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, was born a British subject on the island of Nevis in the West Indies in 1755 (previously believed to be 1757). He came of good family on both sides. His father, James Hamilton, a Scottish merchant of St. Christopher, was a younger son of Alexander Hamilton of Grange, Lanarkshire, Scotland, by Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Robert, Laird of Pollock. His mother, Rachael Faucett Lavien, of French Huguenot descent, never married James Hamilton. When very young she had married John Michael Lavien; unhappy, she soon left. Though her husband procured a divorce in 1759, the court forbade her remarriage. Living out of wedlock, as was not uncommon at the time, Rachel and James Hamilton, in addition to Alexander, had a second son, James.

When business misfortunes forced his father into bankruptcy and his mother died in 1768, young Hamilton was thrown upon the care of maternal relatives at St Croix. At age 12 he entered the counting house of Nicholas Cruger. Shortly afterward Cruger went abroad and confidently left the boy in charge of the business.

The extraordinary specimens we possess of Hamilton’s mercantile correspondence and friendly letters from this time attest to an astonishing poise and maturity of mind and self-conscious ambition. His opportunities for regular schooling must have been scant; but he cultivated friends who discerned his talents and encouraged their development. He formed early the habits of wide reading and industrious study that were to persist through his life. In addition, his command of French — common enough in the Caribbean — would serve him well during the American Revolutionary War.

Emigration and Revolution

In 1772 some friends, impressed by a description he wrote of a terrible West Indian hurricane in that year, made it possible for him to go to New York to complete his education. Arriving in autumn 1772, he prepared for college at Elizabethtown, New Jersey and in 1774 he entered King’s College (now Columbia University) in New York.

His studies, however, were interrupted by the colonial conflict with Britain. A visit to Boston seems to have thoroughly confirmed the conclusion, to which reason had already led him, that he should cast his fortunes in with the Patriots; he threw himself into their cause with ardor. In 1774 and 1775 he wrote two anonymous and influential pamphlets (which were attributed to John Jay). They show remarkable maturity and controversial ability, and rank high among the political arguments of the time.

Hamilton organized an artillery company and was awarded its captaincy on examination. He won the interest of Nathanael Greene and George Washington by the proficiency and bravery he displayed in the campaign of 1776 in and near New York City. In March 1777 he joined Washington’s staff with the rank of lieutenant colonel and for four years served as his aide-de-camp and confidant. The important duties with which he was entrusted attest to Washington’s faith in his abilities and character. Then and afterwards their relationship was one of reciprocal confidence and respect.

But Hamilton was ambitious for military glory — an ambition he never lost. He became impatient with his duties to Washington and in February 1781 he seized on a slight reprimand from the Commander-in-Chief as an excuse for abandoning his staff position. He secured a field command (through Washington) and later won laurels for leading the American assault on British fortifications at the Siege of Yorktown (1781).

Marriage and Federal Union

Falling in love with Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of General Philip Schuyler, Hamilton married her in December 1780, and coincidentally aligned himself with one of the most distinguished families in New York. Meanwhile, he had begun the political activities upon which his fame principally rests. In letters from 1779 to 1781, he correctly diagnoses the ills of the Confederation and suggests, with admirable prescience, the necessity of centralization in its governmental powers. Indeed, he was one of the first — if not to conceive then at least to suggest — checks on the anarchic tendencies of the time.

After a frustrating year’s service in Congress (1782 – 83), in which he was unable to achieve the ends he sought, he settled down to legal practice and raising a family in New York.

The call for the Annapolis Convention in 1786 was an opportunity. As a delegate from New York he supported James Madison in inducing the Convention to exceed its delegated powers (himself drafting the call) to summon a Federal Convention at Philadelphia in 1787. He secured a place in the New York delegation.

On 18 June 1787 the 32-year-old Hamilton made a remarkable six-hour speech. He held up the British government as the best model in the world. Though fully conscious that monarchy in America was impossible, he wished to obtain the next best solution in an aristocratic, strongly centralized, coercive, but representative union, with devices to give weight to the influence of class and property. Following his speech, there was silence; his plan had no chance of success.

With his anti-federal New York colleagues present his own vote for any kind of centralized government was useless. So after a month at the Convention he returned home. But when the other New York delegates also withdrew from Philadelphia, he hurried back. He alone signed the Constitution for his state.

Unable to obtain what he wished, he nevertheless used his great talents to secure the adoption of the Constitution that was agreed at the Convention. New York’s vote for the Constitution was uncertain. He therefore joined Madison and John Jay to write The Federalist (1787 – 88), which not only contains the greatest of his writings, but with over half its contents written by him, is indeed the greatest individual contribution to the adoption of the new government.

Sheer will and reasoning could hardly be more brilliantly and effectively exhibited than they were by Hamilton in the New York Convention of 1788, whose vote he won, and against the greatest odds, for the ratification of the Constitution.

Secretary of the Treasury

At the formation of the new government, Washington asked Hamilton to become Secretary of the Treasury; he also became President Washington’s closest adviser.

Congress immediately referred to him an assortment of questions and problems. In response, Hamilton penned a succession of papers that have left the strongest imprint on the administrative organization of the United States government. There were two reports on public credit that upheld an ideal of national honor higher than the prevalent popular principles; a report on manufactures, advocating their encouragement (a famous report that has served ever since as a storehouse of arguments for a national protective policy); a report favoring the establishment of a national bank, which derived its argument based on the doctrine of implied powers

in the Constitution, and on the application that Congress may do anything that can be made, through the medium of money, to serve the general welfare

of the United States (doctrines that, through judicial interpretation, have since revolutionized the Constitution); and, finally, a vast mass of detailed work by which order and efficiency were given to national finances.

The success of Hamilton’s financial measures was immediate and remarkable. They did not, as is often but loosely said, create economic prosperity; but they did propel it forward with order, hope and confidence. His ultimate purpose was always the strengthening of the Union. Before particularizing his political theories and the political import of his financial measures, the remaining events of his life may be traced.

His activity in the cabinet was by no means confined to the finances. He regarded himself, apparently, as a kind of prime minister — the prime member of Washington’s cabinet — and sometimes overstepped the limits of his office by interfering with departments outside of Treasury. The heterogeneous character of the duties placed upon the Department of Treasury by Congress seemed in fact to reflect the English idea of its primacy. And Hamilton’s influence over Washington (in so far as any man could have influence) was predominant. Thus it happens that in foreign affairs, whatever credit properly belongs to the Federalists as a party for the adoption of that principle of neutrality which became the traditional policy of the United States, must be regarded as largely due to Hamilton.

But allowance must be made for the advantage of initiative which belonged to any party that organized that first government. On the question of neutrality in foreign affairs, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (favoring the French) sharply disagreed with Hamilton. On domestic policy their differences were vital. In their conflicts over financial policy, they organized themselves, on the basis of varying tenets and ideals which have never ceased conflict in American politics, into the two great parties of the Federalists and the (Jeffersonian) Democratic Republicans.

In 1792 and 1793, the Jeffersonian faction in Congress began a series of investigations calling into question whether Hamilton was benefiting financially from Treasury’s policies. Inadvertently, Congress also uncovered an affair that he had had with a Maria Reynolds, as well as ongoing blackmail from her husband. As regards any financial impropriety, Hamilton compiled lengthy reports accounting for every penny. As regards the affair, when Hamilton could not get an explicit promise from James Monroe in July 1797 to not go public with the information, Hamilton published it himself. His pamphlet discussed his affair and his relationship with Maria Reynold’s husband in considerable detail. Ridiculed by some, applauded by others, Hamilton nevertheless hoped that by telling all, he would maintain his viability for future public service. But his political career was effectively destroyed.

Federalist leadership

At the end of January 1795, Hamilton resigned his position as Treasury Secretary and returned to the practice of law in New York — leaving it for public service only from 1798 to 1800 when he was the active head, under Washington (who insisted that Hamilton should be second only to himself), of the army organized for the quasi-war

with France. Yet even in private life he remained the continual and chief adviser of Washington, notably in the crisis engendered by the Jay Treaty (of which Hamilton approved), and in drafting Washington’s Farewell Address (1796).

After Washington’s death in 1799, the Federalist leadership was divided. John Adams, the nominal head of the Federalists, had prestige from a varied and great career, and he had greater strength among the people than any other party member. Hamilton, on the other hand, controlled practically all the leaders of lesser rank, including the greater part of the most distinguished men of the country. But Hamilton was not a popular leader. When his passions were not involved, or when they were repressed by a crisis, he was farsighted and his judgment of men was excellent. In the main, however — as Hamilton himself once said — his heart was ever the master of his judgment. He was, indeed, not above intrigue, but was unsuccessful in it. He was a fighter through and through. His courage was superb. He was also indiscreet in utterance, impolitic in management, opinionated, uncritically self-confident, and uncompromising in nature and in methods.

His faults are nowhere better shown than in his quarrel with John Adams. In order to accomplish ends deemed by him, personally, to be desirable, Hamilton used the political fortunes of Adams as a mere hazard in his maneuvers. Moreover, after Adams became president, Hamilton constantly advised members of the President’s own cabinet, and through them endeavored to control Adams’s policy. Finally, on the eve of the crucial election of 1800, he wrote a bitter personal attack on the President (containing much confidential cabinet information), which was intended for private circulation, but which was secured and published by Aaron Burr.

The mention of Burr leads to the fatal end of another great political nemesis in Hamilton’s life. He read Burr’s character correctly from the beginning and deemed it a patriotic duty to thwart him in his ambitions. Hamilton successively defeated Burr’s hopes of a foreign mission, the presidency, and the governorship of New York. In his conversations and letters Hamilton repeatedly and unsparingly denounced him. If these denunciations were known to Burr they were ignored until his last defeat. After that he forced a quarrel over a trivial bit of hearsay, that Hamilton had said he had a despicable

opinion of Burr. Hamilton accepted a challenge from him, believing — as he explained in a letter written before going to his death — that a compliance with the dueling practices of the time was inseparable from the ability to be useful in public affairs in the future.

The duel was fought at Weehawken, below the cliffs of the New Jersey Palisades, across the Hudson River from Manhattan. At the first fire Hamilton fell and, though he did not intend to fire, his pistol discharged. Mortally wounded, he died on the following day on 12 July 1804. The tragic close of his career relaxed political rivalries for the moment; his death was very generally deplored as a national calamity.

Political philosophy

No emphasis, however strong, upon the mere consecutive personal successes of Hamilton’s life is sufficient to show the measure of his importance in American history. That importance lies, to a large extent, in the political ideas for which he stood. His mind was eminently legal.

He was the unrivaled controversialist of the time. His writings, which are distinguished by clarity, vigor, and rigid reasoning — rather than by any show of scholarship — are, in general, strikingly empirical in basis. He drew his theories from his experiences of the Revolutionary period, and he hardly modified them during his life.

In his earliest pamphlets (1774 – 1775) he started out with the ordinary pre-Revolutionary Whig doctrines of natural rights and liberty. But with the first experience of semi-anarchic states’ rights and individualism, he ended his fervor for ideas so essentially alien to his practical, logical mind. And they have no place in his later writings.

The feeble inadequacy of conception, infirmity of power, factional jealousy, disintegrating particularism, and vicious finance of the Confederation were recognized by many others — but no one else saw so clearly the concrete nationalistic remedies for these ills or pursued remedial ends so constantly, so ably, and so consistently. As an immigrant, Hamilton had no local ties. He was by instinct a continentalist, a federalist. He wanted a strong union and energetic government that would rest as much as possible on the shoulders of the people and as little as possible on those of the state legislatures

; that would have the support of wealth and class; and that would curb the states to such an entire subordination

as to be unhindered by those bodies.

To accomplish these ends he aimed with extraordinary skill in all his financial measures. As early as 1776 he urged the direct collection of federal taxes by federal agents. From 1779 onward we trace the idea of supporting government by the interest of the propertied classes. From 1781 onward there is the idea that a not-excessive public debt would be a blessing in giving cohesiveness to the union. Hence his device by which the federal government, assuming the war debts of the states, would secure greater resources, basing itself on a high ideal of nationalism, and strengthening its hold on the propertied class as well as the individual citizen.

In his report on manufactures his chief avowed motive was to strengthen the Union. To the same end, he conceived the constitutional doctrines of liberal construction, implied powers,

and the general welfare,

which were later embodied in the decisions of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. The idea of nationalism pervaded and quickened his life and works. With one great exception, the declaration by French Prime Minister and historian François Guizot (1787 – 1874) is hardly an exaggeration: there is not in the Constitution of the United States an element of order, of force, of duration which Alexander Hamilton did not powerfully contribute to introduce into it and to cause to predominate.

Reactionary

The exception, as American history has shown, was democracy. The loose and barren rule of the Confederation seemed to conservative minds such as Hamilton’s to presage, in its strengthening of individualism, a fatal looseness of social restraints, and led him on to a dread of democracy that he never overcame. Liberty, he reminded his fellows in the New York Convention of 1788, seemed to be alone considered in government, but there was another thing equally important, a principle of strength and stability in the organization … and of vigor in its operation.

In fact, Hamilton’s governmental system was repressive. He wanted a system strong enough (he would have said) to overcome the anarchic tendencies loosed by war and represented by those notions of natural rights which he had himself once championed; strong enough to overbear all local, state, and sectional prejudices, powers or influence; and to control — not, as Jefferson would have it, to be controlled by — the people. Confidence in the integrity, the self-control, and the good judgment of the people, which was the soul of Jefferson’s political faith, had almost no place in Hamilton’s theories. Men,

he said, are reasoning rather than reasonable animals.

The charge that he labored to introduce monarchy by intrigue is an underestimate of his good sense. But Hamilton’s thinking did carry him afoul of current democratic philosophy. As he said, he presented his plan at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 not as attainable, but as a model to which we ought to approach as far as possible.

Moreover, he held throughout his life a belief in its principles and in its superiority over the government actually created. Although its inconsistency with American tendencies was yearly more apparent, he never ceased to avow on all occasions his aristocratic, slightly monarchical, affinity. Moreover he was not alone; his preference for at least an aristocratic republic was shared by many other men of talent. In parallel with the sometimes outrageous and intemperate interpretations of his designs by Jefferson, it is not so strange that Democratic opponents mistook Hamilton’s theoretical predilections for positive designs.

From the beginning of the excesses of the French Revolution, he persuaded himself that American democracy might at any moment crush the restraints of the Constitution and careen to license and anarchy. After the Democratic victory of 1800, his letters, full of retrospective judgments and interesting outlooks, are only rarely relieved in their pessimistic outlook by flashes of hope and courage. His last letter on politics, written two days before his death, illustrates the two sides of his thinking. He warns his New England friends against dismemberment of the Union as a clear sacrifice of great positive advantages, without any counterbalancing good; administering no relief to our real disease, which is democracy, the poison of which, by a subdivision, will only be more concentrated in each part, and consequently the more virulent.

To the end he never lost his fear of the states, nor gained faith in the future of the country. He labored still, in mingled hope and apprehension, to prop the frail and worthless fabric.

Except for its spiritual content, he had no understanding of democracy, and even in its nationalism he had little hope. Yet, to probably no one man, except perhaps to Washington, does American nationalism owe so much.

During the 19th century, the development of the United States was to be a reactive union of Hamiltonian nationalism and Jeffersonian democracy. However, changed conditions since Hamilton’s time — particularly since the Civil War — are likely to create misconceptions as to Hamilton’s position in his own day.

Great constructive statesman as he was, Hamilton was also, from the American point of view, essentially a reactionary. He was the leader of reactionary forces — constructive forces, as it happened — in the critical period after the Revolutionary War and in the period of Federalist supremacy. He was in sympathy with the dominant forces of public life only while they took, during the war, the predominant impress of an imperfect nationalism. Jeffersonian democracy came into power in 1800 in direct line with colonial development. Hamiltonian Federalism was a break in that development. This alone explains how Jefferson could organize the Democratic Party in the face of the brilliant success of the Federalists. Hamilton stigmatized his great opponent as a political fanatic. As realistic as he claimed to be, he could not see — or would not concede — the predominating forces in American life. Hamilton refused to accept that the two great political conquests of the colonial period were local self-government and democracy.

Character and intellect

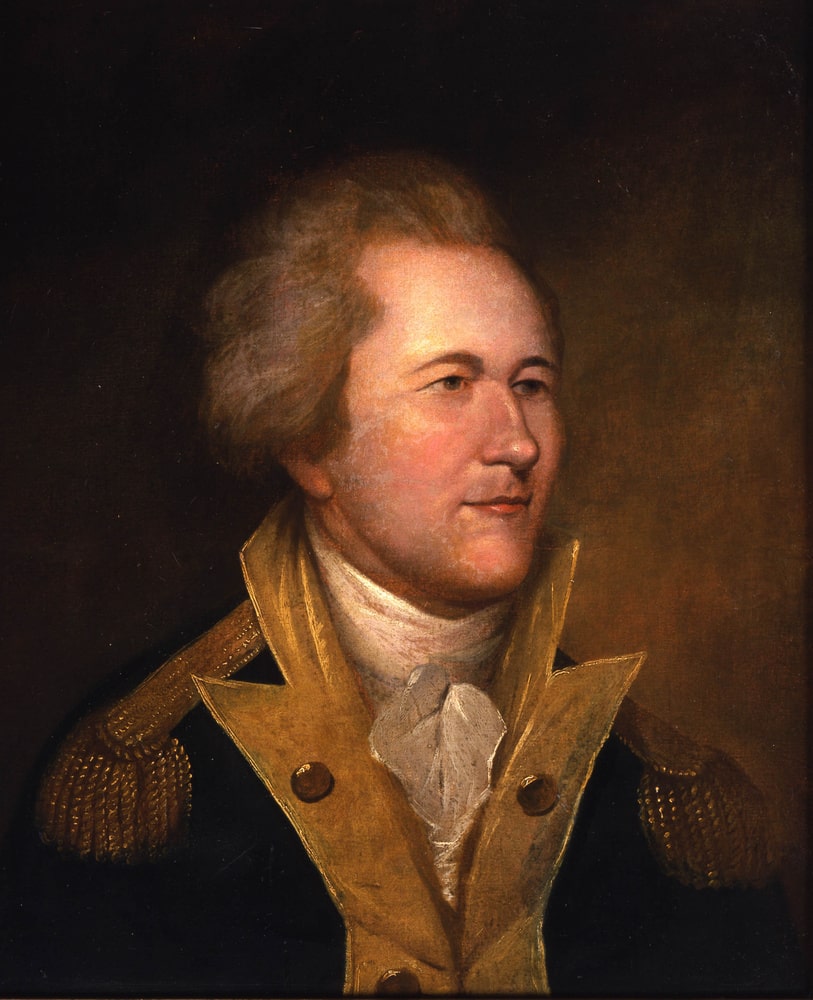

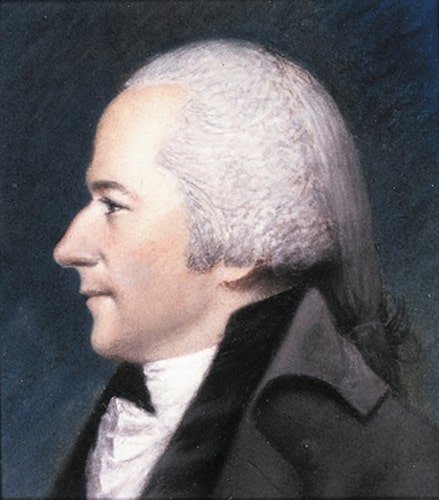

In person Hamilton was rather short and slender; in carriage he was erect, dignified, and graceful. Deep-set, changeable, dark eyes vivified his mobile features and set off his light hair and fair, ruddy complexion. His head in the famous John Trumbull portrait is boldly poised and very striking. The captivating charm of his manners and conversation is attested by all who knew him, and in familiar life he was artlessly simple. He won friends readily and he held them in devoted attachment by the solid worth of a frank, ardent, generous, warm-hearted, and high-minded character. Versatile as were his intellectual powers, he also exhibited a firm will, tireless energy, aggressive courage, and bold self-confidence. His Scotch and Gallic ancestry are evident. His countenance was decidedly Scotch; his nervous speech and bearing and vehement temperament rather French. Agility, clarity, and penetration of mind were matched with logical solidity. Perhaps the word intensity

best sums up his character.

The remarkable quality of his mind lay in the rare combination of acute analysis and grasp of detail with great comprehensiveness of thought. So far as his writings show, he was almost wholly lacking in humor, and in imagination little less so. He certainly had wit, but it is hard to believe he could have had any touch of fancy. In public speaking he often combined a rhetorical effectiveness and emotional intensity that might take the place of imagination, and enabled him, on the coldest theme, to move deeply the feelings of his auditors.

Few Americans have received higher tributes from foreign authorities. Talleyrand, for example, personally impressed when in America with Hamilton’s brilliant qualities, declared that he had the power of divining without reasoning, and compared him to British politician Charles James Fox and Napoleon because he had devine l’Europe.

Of the judgments rendered by his countrymen, Washington’s confidence in his ability and integrity is perhaps the most significant. Chief Justice Marshall ranked him second to Washington alone. But perhaps no judgment is more justly measured than Madison’s in 1831:

That he possessed intellectual powers of the first order, and the moral qualities of integrity and honor in a captivating degree, has been awarded him by a suffrage now universal. If his theory of government deviated from the republican standard he had the candor to avow it, and the greater merit of cooperating faithfully in maturing and supporting a system which was not his choice.