Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 16 March 1751 at Belle Grove Plantation near Port Conway, Virginia.

- James Madison, known as the “Father of the Constitution,” was instrumental in drafting and promoting the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

- He served as the fourth President of the United States from 1809 to 1817, leading the nation during the War of 1812 against Great Britain.

- Madison co-authored the Federalist Papers with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, which were pivotal in securing ratification of the Constitution.

- As Secretary of State under President Jefferson, he oversaw the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the United States.

- He played a key role in the development of the two-party system in the United States, helping to found the Republican Party with Thomas Jefferson.

- Madison’s later years were spent at his Montpelier estate in Virginia, where he continued to be engaged in political discourse and advocacy for individual rights and constitutional governance.

- Died: 28 June 1836 at Montpelier, Virginia.

- Buried at Montpelier.

Introduction

James Madison, the fourth president of the United States, was born at Port Conway, King George County, Virginia, in 1751. His first ancestor in America may possibly have been Captain Isaac Maddyson, a colonist of 1623 mentioned by John Smith as an excellent Indian fighter. His father, also named James, was the owner of large estates in Orange County, Virginia. The son entered the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1769; in the same year, he founded a well-known literary club, The American Whig Society.

He graduated in 1771, but remained for another year at the College, studying — apparently for the ministry — under the direction of John Witherspoon.

In 1772 he returned home to Virginia, where he pursued his reading and studies, especially theology and Hebrew, and acted as a tutor to the younger children of the family.

Beginning political life

In 1775 he became chairman of the Committee of Public Safety for Orange County and wrote its response to Patrick Henry’s call for the arming of a colonial militia. In the spring of 1776 he was chosen a delegate to the Fifth Virginia Convention, where he was on the committee which drafted the constitution for the state. He proposed an amendment which declared that all men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise

of religion, which was more radical than the similar one offered by George Mason. It was not adopted.

In 1777, largely, it seems, because he refused to follow the custom of treating the voters to rum and punch, he was not re-elected. In November of the same year he was chosen a member of the privy council (council of state), in which he acted as an interpreter for a few months, then as secretary to Governor Patrick Henry. He played a prominent role in Virginia until the end of 1779, when he was elected to the Continental Congress.

Delegate to the Continental Congress

As a delegate to Congress during the final stages of the Revolutionary War, in 1780 Madison drafted instructions to John Jay, then representing the United States at Madrid, that in negotiations with Spain he should insist upon the free navigation of the Mississippi.

When the confederation was nearly in a state of collapse because of the failure of the states to respond to fiscal requisitions from Congress, Madison was among the first to advocate the granting of additional powers to Congress. With inflation rampant, he urged that Congress forbid the states from issuing even more paper money. In 1781, he favored an amendment to the Articles of Confederation that gave Congress the power to enforce its requisitions, and in 1783, despite the open opposition of the Virginia legislature — which considered the Virginian delegates wholly subject to its instructions — he advocated that the states should grant to Congress for 25 years the authority to levy an import duty, and he suggested a scheme to provide for the interest on the debt not raised by the import duty. This was to be apportioned among the states on the basis of population, where slaves would be counted as three-fifths — a ratio suggested by Madison himself (and one that would later became infamous in the U.S. Constitution. Accompanying this plan was an address to the states drawn up by Madison, and one of the ablest of his state papers.

In the same year, along with Oliver Ellsworth (Connecticut), Nathaniel Gorham (Massachusetts), Gunning Bedford (Delaware), and John Rutledge (South Carolina), he was a member of the committee that reported on the Virginia proposal on the cession to the Confederation of the back lands,

or unoccupied Western territory, held by several of the states. The report was a skillful compromise which secured the approval of the rather exigent Virginia House of Delegates.

The Virginia House of Delegates

In November 1783 when Madison’s term in Congress expired, he returned to Virginia and studied law. In the following year he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. As a member of its committee on religion he opposed the giving of special privileges to the Episcopal Church or to any other religion. His Memorial and Remonstrance against the proposed assessment for churches of the state was widely circulated and procured its defeat. On the 26 December 1785, Thomas Jefferson’s Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom (written seven years earlier), was introduced by Madison and passed as the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom.

As in Continental Congress, Madison opposed the further issue of paper money in the Virginia House of Delegates. He also tried to induce the legislature to repeal the law confiscating British debts, but he did not lose sight of the interests of the South. The boundary between Virginia and Maryland, according to the Baltimore grant, was the south shore of the Potomac — a line which Virginia had agreed to on condition of free navigation of the river and the Chesapeake Bay. Virginia now feared that too much had been given up, and desired joint regulation of the navigation and commerce of the river by Maryland and Virginia. On Madison’s proposal, commissioners from the two states met at Alexandria and at Mount Vernon in March 1785. The Maryland legislature approved the Mount Vernon agreement and proposed to invite Pennsylvania and Delaware to join in the arrangement. Madison, seeing an opportunity for more general concert in regard to commerce and trade (and possibly for the increase of the power of Congress), proposed that all the states should be invited to send commissioners to consider commercial questions, and a resolution to that effect was adopted in January 1786 by the Virginia legislature.

This led to the Annapolis Convention of 1786, which in turn led to the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention of 1787.

The Constitutional Convention

In April 1787 Madison had written a paper, The Vices of the Political System of the United States. From his study of confederacies, ancient and modern, later summed up in The Federalist (numbers 17, 18, and 19), he concluded that no confederacy could long endure if it acted upon states only and not directly upon individuals. As the time for the Constitutional Convention approached, he drew up an outline of a new system of government, the basis for what became The Virginia Plan

(sometimes called the Randolph Plan, since it was presented at the Convention by fellow Virginia delegate Edmund Randolph).

Madison’s scheme, as expressed in a letter to George Washington (16 April 1787) was that individual sovereignty of states was irreconcilable with aggregate sovereignty and that the consolidation of the whole into one simple republic would be as inexpedient as it is unattainable.

He considered, as a practical middle ground, (1) changing the basis of representation in Congress from states to population; (2) giving the national government positive and complete authority in all cases which require uniformity

; (3) giving it a negative on all state laws, a power which might best be vested in the Senate, a comparatively permanent body; (4) electing the lower house — the more numerous one — for a short term; (5) providing for a national executive, for extending the national supremacy over the judiciary and the militia, for a council to revise all laws, and for an express statement of the right of coercion; and finally, (6) obtaining the ratification of a new constitutional instrument from the people, and not merely from the legislatures.

To the surprise of most of the delegates, who had come to Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation, the old constitution was instead set aside. The Virginia Plan became the basis of the Convention’s deliberations. Through a long, hot summer, with windows shut to ensure secrecy, the Constitution was favorably accepted by 39 delegates (with three refusing to sign) on 17 September 1787.

Among the features of the Virginia Plan were the following: proportionate representation in the Senate and the election of its members by the lower house out of a proper number of persons nominated by the individual legislatures

; the vesting in the national congress of power to negate state acts; and the establishment of a council of revision (the executive and a convenient number of national judges) with veto power over all laws passed by the national congress.

Madison took a leading part in the debates of the convention, of which he kept full and careful notes (afterwards published by order of Congress in 1843). Many minute and wise provisions are due to him, and he spoke before the convention more frequently than any other delegate except for James Wilson and Gouverneur Morris.

In spite of the opposition to the Constitution by Virginia delegates George Mason and Edmund Randolph, Madison induced the state’s delegation to stand by the Constitution in the Convention. His influence helped shape the form of the final draft of the Constitution, but the labor was not finished with this draft.

Ratification

That the Constitution was accepted by the people was due in an eminent degree to the efforts of Madison, who, to place the new Constitution before the public in its true light, and to meet the objections brought against it, joined Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist, a series of 85 essays — 29 of which were written by Madison.

In the Virginia Convention for ratifying the Constitution (June 1788), when eight states had already ratified, it seemed that Virginia’s vote would be needed to make the necessary nine — and it appeared that New York would vote against the Constitution if Virginia did not vote for it. So Madison argued for ratification against his ablest opponents: Patrick Henry, George Mason, James Monroe, Benjamin Harrison, William Grayson and John Tyler. He answered their objections in detail, calmly, and with an intellectual power and earnestness that carried the Convention. The result was a victory for Madison and for his lieutenants — Edmund Pendleton, John Marshall, George Nicholas, Harry Innes and Henry Lee — against an originally adverse public opinion and against the eloquence of the opponents of the Constitution.

(As it turned out, New Hampshire cast the deciding ninth vote shortly before that of Virginia.)

However, Madison’s labors in behalf of the Constitution now alienated from him valuable political support in Virginia. He was defeated by Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson in his candidacy for the United States Senate. However, in his own district he was chosen a representative to Congress, defeating James Monroe, who seems to have had the powerful support of Patrick Henry.

Representative in the U.S. Congress

Madison took his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in April 1789 and assumed a leading part in the necessary legislation for the organization of the new government. He drafted a Tariff Bill giving notable advantages to nations with which the United States had commercial treaties, hoping to force Great Britain into a similar treaty. It was his belief that such a system of retaliation would remove the possibility of war arising from commercial quarrels. But his policy of discrimination against England was rejected by Congress. He introduced resolutions calling for the establishment of three executive departments, Foreign Affairs, Treasury, and War, the head of each removable by the president. Most important of all, he proposed nine amendments to the constitution, embodying suggestions made by a number of the ratifying states — especially those made by Virginia at the insistance of George Mason. The essential principles of Madison’s proposed amendments were included in a Bill of Rights, adopted by the states in the form of ten amendments.

Although a staunch friend of the Constitution, Madison believed that the instrument should be interpreted conservatively and not be made the means of introducing radical innovations. The tide of strict construction was setting in strongly in his state, and he was borne along with the flood. It is also probable that Jefferson’s influence over Madison, which was greater than Hamilton’s, contributed to this result. Madison now opposed Hamilton’s measures for the funding of the debt, the assumption of state debts, and the establishment of a National Bank. On other questions he sided more and more with the opposition, gradually assuming its leadership in the House of Representatives and laboring to confine the powers of the national government within the narrowest possible limits. His most important argument against Hamilton’s Bank was that the Constitution did not provide for it explicitly and could not properly be construed into permitting its creation.

Madison, Jefferson, and Randolph were consulted by President Washington, and they advised him not to sign the bill providing for the Bank, but Hamilton’s counterargument was successful. On the same constitutional grounds Madison objected to carrying out the recommendations in Hamilton’s famous Report on Manufactures (5 December 1791), which favored a protective tariff; and on this Madison successfully led Congress to oppose it.

During Washington’s second term, Madison strongly criticized the administration for maintaining a neutral position between Great Britain and France, writing for the public press five papers, signed Helvidius.

) He attacked the monarchical prerogative of the executive

as exercised in the proclamation of neutrality in 1793 and denied the president’s right to recognize foreign states. He found in Washington’s attitude — as in Hamilton’s failure to pay an installment of the monies due France — an Anglified complexion,

in direct opposition to the popular sympathy with France and French Republicanism.

In 1794 he tried again his commercial weapons, introducing in the House of Representatives resolutions based on Jefferson’s report on commerce, advising retaliation against Great Britain, and discrimination in commercial and navigation laws in favor of France. He declared that the friends of Jay’s treaty were a British party systematically aiming at an exclusive connection with the British government,

and in 1796 he strenuously but unsuccessfully opposed the appropriation of money to carry this treaty into effect. Still thinking that foreign nations could be coerced through their commercial interests, he scouted as visionary the idea that Great Britain would go to war on a refusal to carry Jay’s treaty into effect, thinking it inconceivable that Great Britain would wantonly make war

upon a country which was the best market she had in the world for her manufactures, and one in which her export trade was so much larger than her imports.

Return to Virginia; U.S. Secretary of State

In 1797 Madison retired from Congress, but not to a life of inactivity. In 1798 he joined Jefferson in opposing the Alien and Sedition Laws, and Madison himself wrote the resolutions of the Virginia legislature declaring that it viewed

The Virginia resolutions and the Kentucky resolutions (the latter drafted by Jefferson) were met by dissenting resolutions from the New England states and from New York and Delaware. In answer to these, Madison — who had become a member of the Virginia legislature in the autumn of 1799 — wrote a report for the committee to which they were referred that elaborated and sustained in every point the phraseology of the Virginia resolutions.

Upon the accession of the Republican party to power in 1801, Madison became Secretary of State in President Jefferson’s cabinet, a position for which he was well suited both because he possessed to a remarkable degree the gifts of careful thinking, discreet and able speaking, and of large constructive ability; and because he was well versed in constitutional and international law, practicing a fairness in discussion essential to a diplomat.

During the eight years that he held the portfolio of state he had to continually defend the neutral rights of the United States against the encroachments of European belligerents. In 1806 he published An Examination of the British Doctrine which subjects to Capture a Neutral Trade not open in Time of Peace, a careful argument — with a minute examination of authorities on international law — against the rule of war of 1756 extended by Great Britain in 1793 and 1803. And with the purchase of Louisiana Territory in 1803, the campaign that Madison had begun in 1780 for the free navigation of the Mississippi was brought to a successful close.

Presidency and the War of 1812

The candidate of the Republican Party in 1808, Madison — although bitterly opposed in the party by John Randolph and George Clinton — was elected president. He defeated Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the Federalist candidate, by 122 votes to 47.

Madison had no false hopes of placating the Federalist opposition, but as the preceding administration was one with which he was in harmony, his position was different from that of Jefferson in 1801; he had less occasion for removing Federalists from office. He continued to follow Jefferson’s peace policy — or, more correctly, his own peace policy — of commercial restrictions to coerce Great Britain and France.

Then in 1812 he was forced to change these futile commercial weapons for a policy of war, which was very popular with the extremist French wing of the Republican Party. There is a charge, which has never been proved or disproved, that Madison’s real desire was for peace, but that in order to secure the re-nomination he yielded to that wing of his party which was resolved on war with Great Britain. The only certain fact is that Madison, whatever his personal feelings in this matter, acted according to the wishes of a majority of the Republicans. Whether in doing so he was influenced by the desire of another nomination is largely a matter of conjecture. On 18 May 1812, Madison was re-nominated; he issued his war message on 1 June, and in the November elections he was re-elected, defeating DeWitt Clinton by 128 votes to 89.

His administration during the war was pitiably weak. His cabinet in great part had been dictated to him in 1809 by a senatorial clique, and it was hopelessly discordant. For two years he was to all intents and purposes his own secretary of state, Robert Smith being a mere figurehead that he gladly got rid of in 1811, when he gave James Monroe the vacant place. Madison himself had attempted alternately to prevent war using his commercial weapons

and to prepare the country for going to war. However, he met with no success, both because of the tricky diplomacy of Great Britain and of France and because of the general distrust of him coupled with the particular opposition to the war of the prosperous New England Federalists — who suggested with the utmost seriousness that his resignation should be demanded. In brief, Madison was too much the mere scholar to prove a strong leader in such a crisis.

The supreme disgrace of the administration was the capture and partial destruction in August 1814 of the city of Washington – this was due, however, to incompetence of the military and not to any lack of prudence on the cabinet’s part. In general, Congress was more to blame than either the president or his official family, or the army officers. With the declaration of peace the president again gained a momentary popularity much like that he had won in 1809 by his apparent willingness at that time to fight France.

Final years

Retiring from the presidency in 1817, Madison returned to his home, Montpelier, in Orange County, Virginia. Madison’s home was peculiarly a center for literary travelers in his last years. He took a great interest in education — his library was left to the University of Virginia (where it was destroyed by fire in 1895) — in emancipation, and, to the very last, in agricultural questions. But like Jefferson’s Monticello and Monroe’s Oak Hill, the plantation estate of Montpelier was, despite the labor of enslaved people, nearly ruinous financially.

In 1829 Madison once more served in an official capacity when he became a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention, where he served on several of its committees.

He died at Montpelier in 1836.

Personal life and legacy

Madison married, in 1794, Dorothy Payne Todd (1772—1849), widow of John Todd, a Philadelphia lawyer. She had great social charm, and upon Madison’s entering Jefferson’s cabinet became first lady

in Washington society. Her plump beauty was often remarked — in contrast to her husband’s delicate and feeble figure and wizened face. For even in his prime Madison was, as Henry Adams says, a small man, quiet, somewhat precise in manner, pleasant, fond of conversation, with a certain mixture of ease and dignity in his address.

Dolley’s son, John Payne Todd, spoiled by both mother and step-father, became a wild young fellow who added his debts to the already heavy burden of Montpelier.

Madison’s greatest and truest fame is as the Father of the Constitution.

Among the Founding Fathers, he was the broadest and most accurate scholar, and an expert in constitutional history and theory. Contrasting him with Jefferson, Henry Clay said that Jefferson had more genius, Madison more judgment and common sense; that Jefferson was a visionary and a theorist while Madison was cool, dispassionate, practical, and safe.

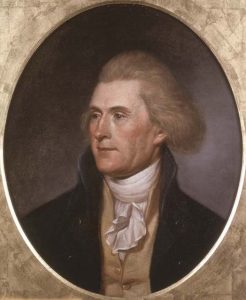

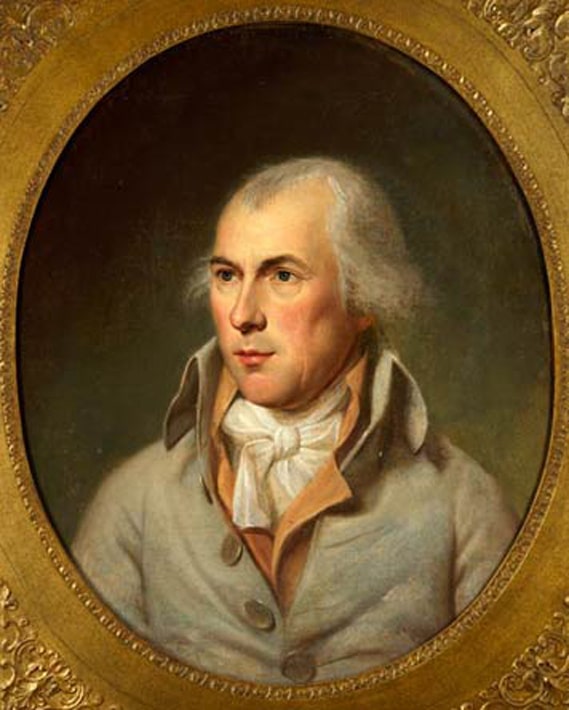

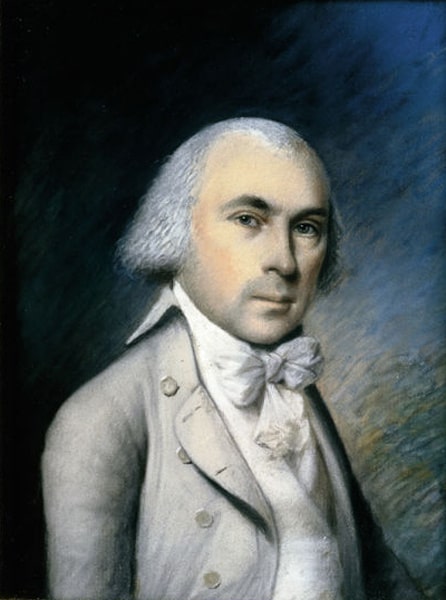

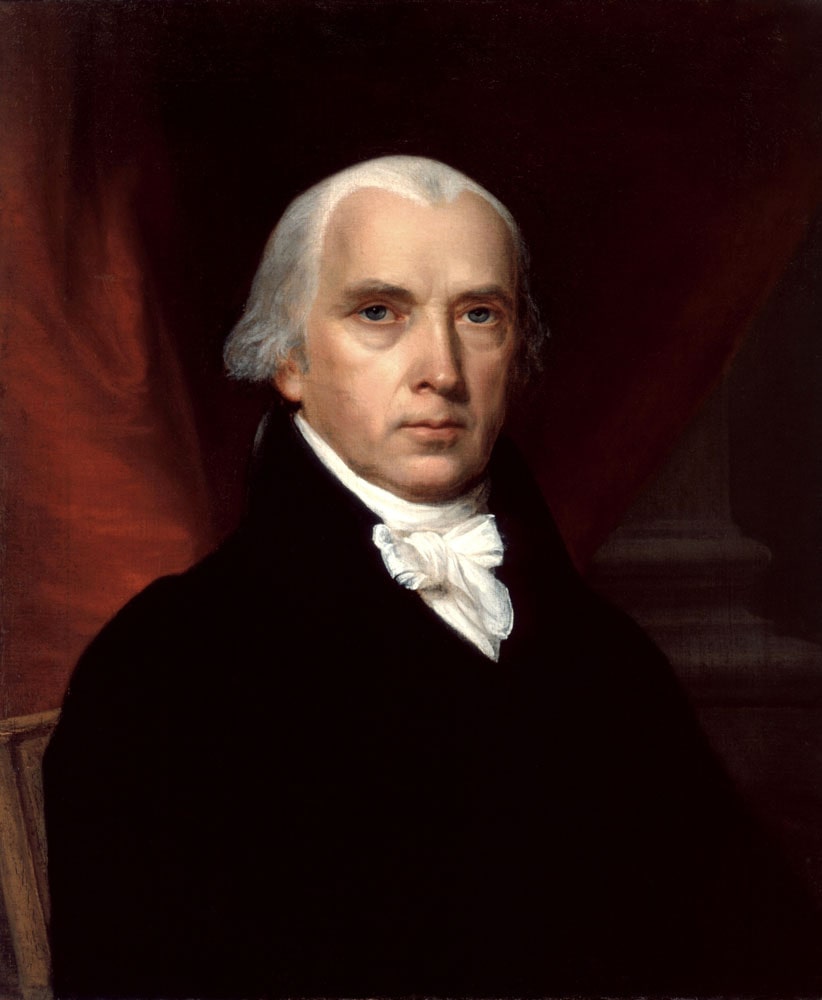

Madison’s portrait was painted by Gilbert Stuart and by Charles Willson Peale; Giuseppe Ceracchi made a marble bust of him in 1792 and John H.J. Browere another in 1827. Dignified, though a little stiff, he had a strong sense of humor and liked to tell a good story or an off-color joke. In the great causes for which he fought in his earlier years — religious freedom and the separation of church and state, the free navigation of the Mississippi, and the adoption of the U.S. Constitution — he met with success. The commercial weapons

with which he wished to prevent armed conflict proved less than useful in his day, though they have been used with greater effect in ours.