Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 4 January 1746 in Byberry, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania.

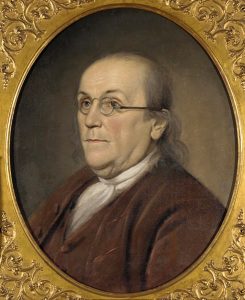

- Following graduation from Medical School at the University of Edinburgh (1768), Rush met some of the famous men of his age. In London, he met Benjamin Franklin and dined with Anglo-American artist Benjamin West — where he met another artist, Sir Joshua Reynolds, who in turn introduced him to writers Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith. In Paris, he met French philosophe Denis Diderot, from whom he received a letter of introduction to Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume.

- Rush also helped convince a reluctant John Witherspoon, age 45, to leave his parish in Paisley, Scotland, and accept an offer from the College of New Jersey (Princeton) to become its sixth president.

- At the age of 24, Rush was elected to the “Chemical Chair” at the College of Philadelphia (1769) — becoming the first professor of chemistry in the Americas.

- Dr. Rush became Surgeon General of the Middle Department of the Continental Army (1776) and served at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton.

- Rush published Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers (1777 and 1778), in which he described his experience on the battlefield and the proper methods for treating common war injuries. The work was so useful that it continued to be used by the American army into the Civil War.

- Outraged by conditions in the army hospitals, and unable to have the Director General removed by either General Washington or Continental Congress, Rush resigned his commission (1778).

- In 1783, Rush founded Dickinson College (in Carlisle, PA) based on the principle that “Freedom is made safe through character and learning.”

- He and James Wilson co-authored Pennsylvania’s state constitution (1790).

- In 1809, Rush encouraged John Adams and Thomas Jefferson — who, once friends, had become rivals and estranged in the 1790s — to reconcile their friendship. In 1812, Adams and Jefferson exchanged 13 letters — which began a remarkable correspondence between these two Founders — of over 150 letters before their deaths on 4 July 1826.

- Following Dr. Rush’s death in 1813, Jefferson wrote to Adams: “Another of our friends of seventy-six is gone, my dear sir; another of the co-signers of the independence of our country. A better man than Rush could not have left us, more benevolent, more learned, of finer genius, or more honest” (27-May-1813).

- The year before he died, Rush had published Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind, the first textbook on psychiatry in America.

- Rush taught more than 3,000 medical students during his life; they carried his influence into all parts of a growing American nation.

- Died: 19 April 1813 in Philadelphia.

- Buried at Christ Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia.

Biography

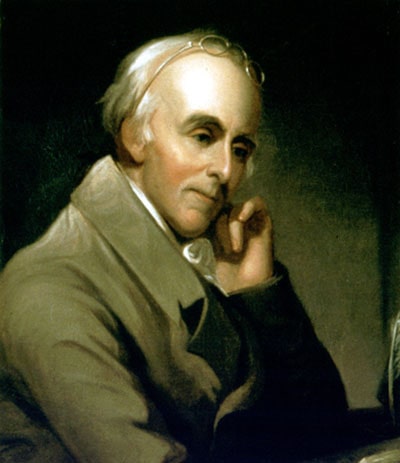

Benjamin Rush, American physician and teacher, was born in Byberry township, near Philadelphia, in 1746. His grandfather was a Quaker gunsmith who had followed William Penn from England in 1683; Rush was born on the homestead founded by him. At age five Rush’s father died, and his mother, Susanna, moved to Philadelphia, where she raised her seven children and managed a grocery shop.

At age eight, Rush’s mother sent him to live with his uncle and aunt in Maryland. He attended the academy conducted by his uncle, Rev. Samuel Finley, then completed his studies at the College of New Jersey (Princeton). In 1760 he graduated when he was not yet 15. (Finley, by the way, became the fifth president of the College of New Jersey in 1761.)

Medical practice, teaching, and marriage

After serving an apprenticeship of six years with a doctor in Philadelphia, Rush studied for two years at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland — then a center of Enlightenment thought and medicine —where he attached himself chiefly to Dr. William Cullen, one of the most important professors at the Medical School. He received his M.D. in 1768, spending another year in hospitals in London and Paris and touring Europe.

By the time he returned to Philadelphia in 1769, Rush had become fluent in French, Italian, and Spanish. Now 24, he opened his own medical practice and it soon flourished. He also became Professor of Chemistry at the College of Philadelphia (founded by Benjamin Franklin), in addition to writing about a variety of topics, including slavery. He organized the first anti-slavery organization in the American colonies — the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage —and later became its president.

In January 1776 Rush married Julia Stockton, daughter of Princeton lawyer Richard Stockton. They would eventually have 13 children together — nine of whom survived into adulthood.

Revolution and politics

As the colonial crisis with Britain came to a head Rush became active in the Sons of Liberty. He also helped to edit and publish a pamphlet by his friend, Thomas Paine, which made the case for independence. Paine had wanted to call it Plain Truth; Rush suggested Common Sense (published 10-Jan-1776).

In June 1776 Rush became a Pennsylvania delegate to the Second Continental Congress and, along with his father-in-law, became one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He served as Surgeon General of the Middle Department of the Continental Army (1776 – 78), but, outraged over conditions in the army hospitals, resigned when he could not get General Washington or Congress to remove the Director General (Dr. Shippen — who had been a former teacher).

Rush became involved in politics once more when he became a delegate to the Pennsylvania Convention that voted for the U.S. Constitution (12-Dec-1787). And in 1790 he and James Wilson co-authored Pennsylvania’s new state constitution. Thereafter he largely retired from politics and dedicated himself to the practice of medicine.

Yellow fever epidemic

In 1789 he exchanged his chemistry lectureship for that of the theory and practice of physic. Then in 1791 when the College of Philadelphia was incorporated into the University of Pennsylvania, he became professor of the Institutes of Medicine and of Clinical Practice. In 1791 he succeeded to the chair of the Theory and Practice of Medicine.

In 1793 yellow fever broke out in Philadelphia and by mid-summer some 6,000 people were stricken. While instructing his family and the other residents to leave the city — including President Washington, a reluctant Thomas Jefferson (serving as Secretary of State), and members of Congress —Dr. Rush stayed behind. Though no one yet understood that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitoes, Rush nonetheless recommended that the local marshes be drained. Seeing more than 100 patients a day, he relied on purges — based on a solution of mercury, calomel, castor oil, and salts — and bloodletting to treat the disease. Many patients began to improve within hours, and most recovered in a few days. (Since yellow fever has no cure, none of these actually treated the disease, but, as administered by Rush, they apparently did no harm.)

As the disease ravaged Philadelphia, doctors were few — most of them having either fled the city or succumbed to the fever — and at one point Rush was one of only three physicians available to treat the sick. He relied on his apprentices to help him, three of whom died, and when Rush himself contracted the fever in October, he underwent the same mercurial purge and bloodletting that he practiced on his patients. By early November, when he was well enough to return to his duties, the number of ill had fallen sharply, and as the cold weather set in, the epidemic ended and residents from the countryside returned to Philadelphia.

Dr. Rush’s efforts were credited with saving thousands from death, and he became famous for his heroism and humanity.

Care for the mentally ill

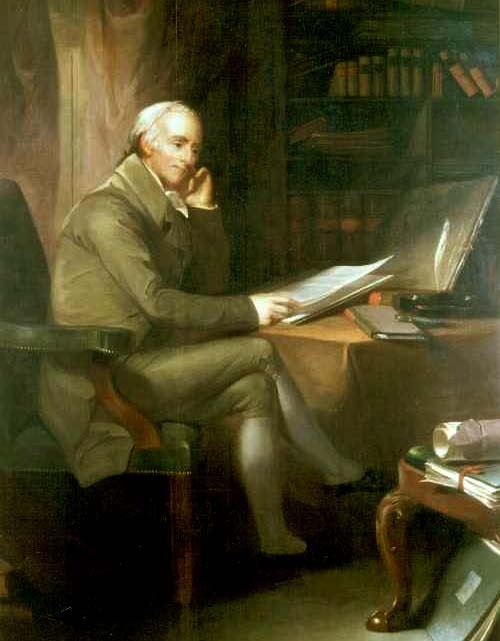

From 1783 when Rush was put in charge of the mental ward at Pennsylvania Hospital, he had been interested in improving treatment for the insane. Now with the yellow fever crisis at an end, he turned his attention to understanding and improving conditions for these marginalized people. One of the first to believe that mental illness is a disease of the mind and not a possession of demons,

Rush demanded that the afflicted be treated as humans. He believed they could handle certain tasks — grinding corn, weaving clothes, or maintaining barns, for example —and in so doing have organization in their lives and even meaning. Though Rush’s ideas were highly controversial, he remained steadfast in his reformist approach, and went further. He urged that caregivers talk and walk with them, and by so doing, perhaps bring them closer to sanity.

In 1813, after five days’ illness from typhus fever, Dr. Benjamin Rush died in Philadelphia.

Legacy

Rush’s writings cover an immense range of subjects, including language, the study of Latin and Greek, the moral faculty, capital punishment, medicine among the American Indians, maple sugar, the blackness of the negro,

the cause of animal life, tobacco smoking, spirit drinking, as well as many more strictly professional topics. From 1789 to 1798 he published Medical Inquiries and Observations in 5 volumes. His classic work, Observations and Inquiries upon the Diseases of the Mind, published in 1812, was the first psychiatric textbook printed in the United States, and today Rush is considered the Father of American Psychiatry.