Contents

Contents

As the American Revolution progressed, the uniforms worn by Continental Army soldiers evolved over time.

The army struggled with disorganization and clothing shortages through much of the war, forcing Washington and Congress to put measures in place to try and give soldiers adequate, consistent clothing.

In this guide, we’ve explained what American soldiers wore during the Revolutionary War, and how their uniforms changed during the conflict.

Beginning of the war

At the very start of the conflict, revolutionary soldiers came from a range of different backgrounds and militias, and wore a range of different outfits, most of which were made up of regular civilian clothes.

Although George Washington recognized the importance of proper military uniform, and worked to address this issue, he had other priorities at the time. The rebels were also suffering from shortages of ammunition, and other essential supplies.

The clothing worn by Continental soldiers would depend on the militia or regiment that they were a part of. Often, hunting shirts would be worn, which were a type of long-sleeve shirt that allowed for easy movement of the arms. Hunting shirts were commonly made of linen, meaning they did not get too hot when moving around the battlefield, and they featured muted colors (often cream, ash, gray, or light brown), for blending into the soldier’s environment. Hunting shirts were also preferred for their durability, and the fact that they could be made cheaply.

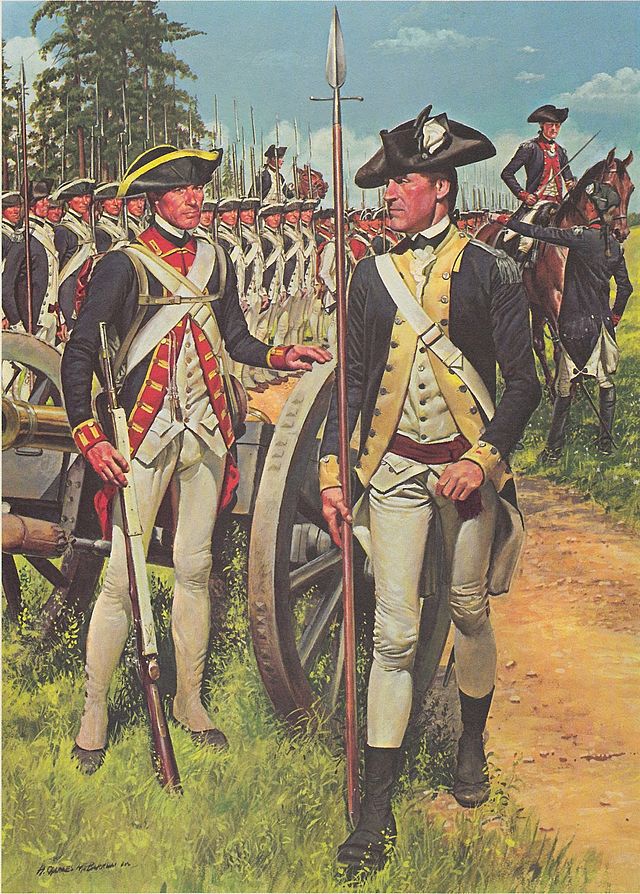

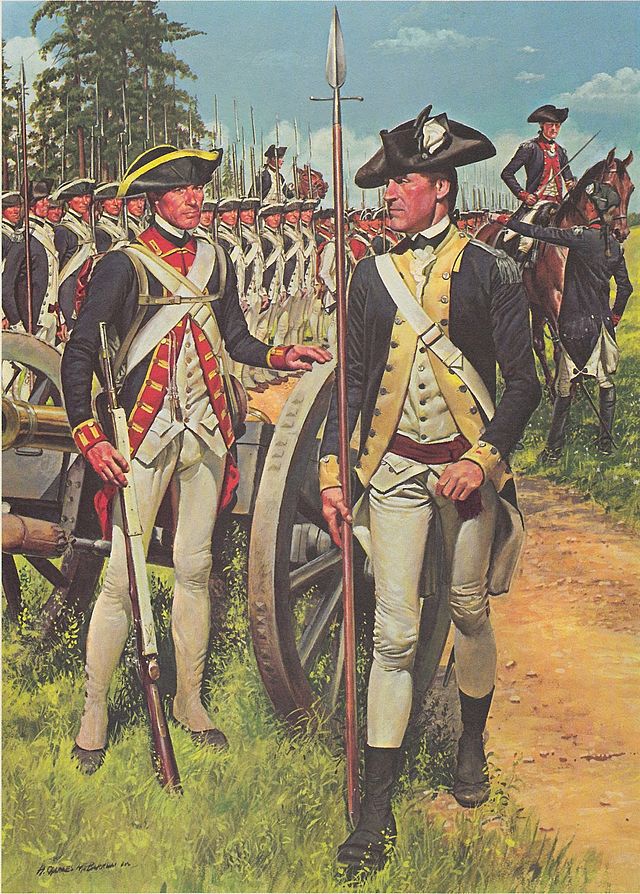

A typical militiaman might have looked like this:

[original image]

- Headgear: black tricorn hats were commonly worn, as was the style in the colonies at the time. They were typically made of felt or leather. A black cockade (a knot of ribbons worn on the edge of the hat) was worn, which was the same color used by the British.

- Upper body: the first layer would be a wool or linen shirt, which was considered sort of like underwear in the 18th century – men would always wear something on top of their shirt. Typically, the next layer was a waistcoat, as this was a typical type of menswear at the time – it was not only used in formal occasions as we do today. Then, the soldier would don their hunting shirt. A long coat might also be worn in very cold weather.

- Lower body: soldiers, like civilians, would wear brown or cream-colored breeches. Breeches are a type of trouser that ends just below the knee. Over the lower legs, wool stockings would be worn.

- Shoes: 18th-century shoes were made of leather, and were often secured with a buckle, instead of laces. They were custom-made for the wearer’s foot, and the leather would mold to the right shape over time. Often, common shoes for everyday use would have a square toe, and the left and right shoes would both have the same shape.

As a result of how common hunting shirts were, the predominant color of early American militia forces was a patchwork of ash or light brown, among other colors, depending on the materials available. However, this varied by regiment – the Green Mountain Boys for example wore green-colored coats.

By contrast, the British Army’s clothing was much more organized from the outset of the war. The Redcoats, as they were known, wore bright red coats made of wool, normally with white facings, although blue or yellow was sometimes used. They would wear white breeches and a white wool vest, and black buckled leather shoes. Headwear would depend on the soldier’s rank, but regular troops would wear a black tricorn hat, made of felt.

Due to the initial disorganization of American forces’ attire, it was sometimes difficult to distinguish different sides on the battlefield. However, the distinctiveness of the Redcoats’ uniforms did help to make them stand out in combat.

1776 onwards

During 1776 and 1777, the Continental Army gradually began using more uniform clothing as the army became more organized.

Initially, many soldiers wore predominantly brown clothing. This was actually the official color of the Continental Army for a short period. But from 1776, they gradually came to adopt the color blue, as was preferred by George Washington, and the soldiers as a whole.

Here is an example uniform worn by the Second South Carolina Regiment of Infantry, who successfully defended the Port of Charleston from the British in 1776.

- Headgear: black leather cap with a white crescent shape stitched into the material, which was the symbol of the regiment, and also seen on their flag.

- Upper body: dark blue overcoat with red facings on the cuffs, lapels, and collar. Above this, a white cross belt was worn, which the soldiers used to attach an ammunition box at the hip. Underneath the coat, a white linen waistcoat was worn.

- Lower body: off-white breeches were worn as trousers, with gaiters. Gaiters were a type of garment used to protect the lower legs and parts of the shoe, as seen here. They were typically made of stiff material such as canvas, to make them resistant to mud and water. Gaiters also helped to keep debris out of soldiers’ shoes.

- Shoes: low cut, black leather shoes were worn, which was typical for most soldiers. Boots were sometimes worn by cavalrymen and officers, and extended up to the knee.

When the Americans joined forces with the French in 1778, the Continental Army began to adopt certain aspects of French fashion at the time, especially among higher-ranking soldiers. Their ally was also able to help provide supplies to the Americans, which led to Washington’s forces adopting more standardized uniforms across the army.

For example, in 1778 and 1779, some officers began using “chapeau de bras”, a type of French bicorn hat that could easily be compressed and carried under the arm, instead of the tricorn hat that had been a staple of the army since the revolution began.

The other effect of the Franco-American alliance was it helped to make the Continental Army gradually begin to look more professional. The French were able to supply higher-quality fabrics and other materials, and their military assistance allowed the Continental Army to spend time focusing on becoming more organized – including with respect to their uniforms.

Clothing supply issues

It is important to note though, as late as 1778, the Continental Army was still not well-supplied or organized enough to ensure that every soldier received proper attire. Many continued to wear brown uniforms and hunting shirts – for example, drummer boys would often wear civilian clothing due to shortages.

Shoes were in particularly short supply. At times, footwear supplied by France was not tough enough for marching in American conditions. This led some soldiers to use whatever materials they could find to protect their feet. If a rabbit or deer was hunted to eat, during resource shortages, a desperate soldier would have used its hide to create makeshift shoes – often, the animal skin would just be wrapped around the foot.

This lack of proper clothing led many soldiers to suffer from frostbite, especially during harsh winters, such as the one experienced in 1777-78 at Valley Forge.

1779 onwards

By 1779, Washington was finally successful in implementing uniform standards that were widely adopted across the Continental Army.

This gave rise to the official Continental Army uniform that springs to mind today when you think about what colonial soldiers wore, although variations still existed due to materials shortages in certain regiments.

- Headgear: the black tricorn hat remained an iconic part of soldiers’ attire throughout the war, especially among privates and corporals. By this stage, the cockade had become black and white, rather than just black. This occurred after the beginning of the Franco-American alliance. France’s cockade was white, leading the Americans to adopt the color.

- Upper body: the most recognizable part of the Continental soldier’s uniform was their dark blue coat. Made of wool, it would feature different highlight colors depending on the colony the soldier was from. It would be trimmed with blue facings for soldiers from the south, red for the middle colonies (except for New York and New Jersey, which were light brown) and white for the New England colonies. Below the coat, a white waistcoat would be worn over a long-sleeve linen shirt. Soldiers would also wear a neck stock – a piece of leather or horsehair worn around the neck, to keep them in a proper upright posture befitting the military.

- Lower body: Continental soldiers would wear white or beige woolen breeches, which would extend to just below the knee. Their lower legs would be protected with a gaiter, extending down to cover the top of the shoe. Later in the war, overalls became more common, which were a type of trouser that combined the breech and the gaiter into a single garment.

- Shoes: soldiers continued to use low-cut black leather shoes that were common throughout the war. Most of the time, the left and right shoes were the exact same shape, and they featured a square toe and a low heel.

Women played a significant role in supplying the Continental Army with the clothing it needed. During the war, they became responsible for making clothes, caring for the family, and working as field nurses, among other duties. They would also repair uniforms that soldiers had fought or died in, since clothing shortages were so severe throughout much of the conflict.

Distinguishing ranks

It was often possible to tell what rank a Continental soldier was based on his uniform.

Privates and non-commissioned officers normally had the normal, regulation uniform. If there were supply issues, they would wear civilian clothing, or whatever appropriate brown or blue-colored attire could be found.

On the other hand, officers would normally have a proper uniform. They might also wear colored epaulets (pieces of fabric or metal sewn into the shoulder), as can be seen on the left shoulder of the lieutenant in the image above, or carry a short saber or a hunting sword as a sign of their status. They also sometimes had a different color of cockade in their hat.

Higher ranking general officers would get access to newer, better quality clothing, with brighter colors and finer fabrics, as well as carrying expertly-crafted swords or scabbards, to signify their rank.

Did American Revolution soldiers wear armor?

Most American soldiers did not wear armor during the American Revolution.

At the time, chainmail and metal body armor used in medieval Europe had been made obsolete by the use of firearms. However, lightweight infantry armor had not been invented yet, so armed forces prioritized clothing that would keep soldiers agile, instead of wearing armor.

The American Revolution was characterized by line tactics, where soldiers would fire shots at each other in open combat. While metal armor did exist, it would have significantly affected soldiers’ ability to move quickly in battle, and dodge enemy musket fire.

Some officers did occasionally wear breastplates – metal armor that would protect the chest – but this was mostly used as a symbol of rank.