Contents

Contents

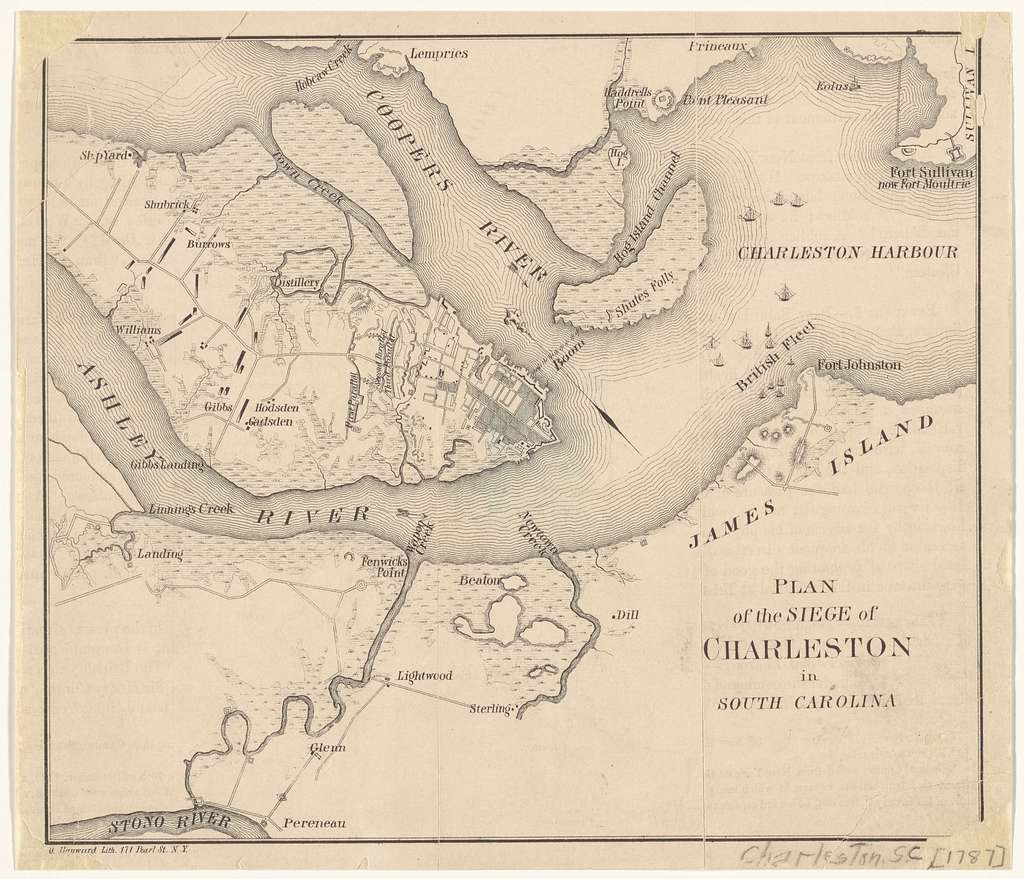

The Siege of Charleston was a battle fought from March 29 to May 12, 1780, during the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution.

The siege ended in a major victory for the British Army, as they captured the city of Charleston, South Carolina.

Summary

Leadup

During the Revolutionary War, British military strategists believed that the southern colonies in America had strong Loyalist tendencies, compared to the more radical New England colonies.

The British believed that the South would be easier to capture, as the Patriots had fewer troops and resources in the area. They also believed that with a British invasion, the local population would rise up against the Continental Army and force them back into their northern strongholds.

As a result, British military strategy often focused on isolating and capturing towns and cities in the southern colonies.

For example, in 1777, the British moved in on Albany, New York, in an attempt to cut off New England from the middle and southern colonies. This resulted in a significant British loss at the Battles of Saratoga.

By 1779, the British were making little headway in the middle and New England colonies, so they renewed their focus on the Southern Campaign, with the main objective of capturing Charleston, South Carolina.

George Washington knew that Charleston was a likely target for an attack, after the British successfully captured Savannah, Georgia, in late 1778.

As a port city, Charleston was in a strong strategic position. With renewed British interest in the south, they knew they could use the city as a launchpad for further campaigns in South Carolina, Georgia, and other southern provinces.

However, despite the significance of Charleston, Washington was preoccupied by the British in New York, and could spare very few men and resources to safeguard the city from a British advance.

From September 1779, Major General Benjamin Lincoln was responsible for defending Charleston. He was in command of approximately 6,500 men, and they immediately began work to build up the city’s fortifications, which were in a state of complete disrepair.

Three months later, General Sir Henry Clinton and General Charles Cornwallis left their position in New York, and sailed south toward Charleston.

In March, after facing a number of storms along the way, the British finally arrived, and met up with further Loyalist militias and Hessians. In total, they had nearly 13,000 soldiers ready to attack Charleston.

Battle

Clinton and Cornwallis quickly encircled Lincoln’s position, and cut off the city from supplies in early April.

The British were easily able to bypass Fort Moultrie (seen in the top right corner of the map above) and bring their ships into the harbor. Commodore Abraham Whipple, leader of the American naval forces in the area, purposefully sank his own ships in the harbor to prevent their capture.

The Americans dug in, but due to a lack of resources, their fortifications were still in relatively poor condition.

By mid-April, it was clear that defeat was inevitable. On the 21st, Lincoln offered to surrender conditionally, with military honors, but this was rejected by Clinton.

On May 11, the British used heated shot to burn many homes in Charleston to the ground, and on the next day, Lincoln surrendered to the British.

The British suffered 99 killed and 117 wounded, while the Americans suffered 89 killed, 138 wounded, and approximately 5,500 captured.

Significance

The defeat at Charleston left the Continental Army completely decimated in the south, allowing the British to immediately consolidate their position in South Carolina and other southern colonies.

This was one of the biggest British victories during the Revolutionary War, and was a significant blow to the Continental Army.

From this point on, there was very little Washington could do in the southern colonies, and he could no longer rely on these regions’ help for major military campaigns.

However, this did not mean that the British had complete control of the South after capturing Charleston.

Instead, the nature of warfare changed, with groups of guerrilla Patriot fighters such as Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion and Thomas Sumter leading small, calculated surprise attacks on British positions.

Facts

- After the siege, the British collected a huge amount of American ammunition and other supplies, including more than 30,000 rounds of ammunition, and nearly 6,000 muskets. When the munitions were put into a magazine for storage, a loaded gun accidentally fired, causing a huge gunpowder explosion, and killing 200 people.

- After the siege, Clinton led the majority of his men back to New York, while Cornwallis stayed with a detachment in Charleston to undertake future operations.

- Because Lincoln was denied honors of war when surrendering, Washington later did the same to Lord Cornwallis after defeating the British at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781. Honors of war meant that the losing side was allowed to march out from their position with drums beating, colors (flags) flying, and weapons shouldered. It also generally allowed for the safety of the troops to be guaranteed, officers to avoid being treated as regular prisoners, and required respect for personal property, prohibiting looting of soldiers’ possessions.

- After their capture, conditions were tough for the American prisoners of war. They were often kept on cramped prisoner ships and run-down military barracks, in poor conditions with little food or water. Many did not survive their imprisonment.

- During the battle, under the Philipsburg Proclamation, escaped slaves who abandoned the Americans and joined the British were promised their freedom, in an attempt to undermine the American labor force and disrupt their supply lines.